Monday night -

did we go Crab Racing - No - Just about the most breathtaking thing we have ever

done.

Fourteen of us got

together and organised the famous taxi driver Cutty to take us at 18:15 up to

the Levera National Park. Cutty organised us a guide and we picked up Dora near

to our destination some two hour drive away.

We stopped just shy of

the beach to have a talk from Dora, who explained a little about the leatherback

turtle species, telling us of one recorded marathon swim of 16,000 miles in

one season, turtles gain sexual maturity somewhere between fifteen and

thirty and their life expectancy being between eighty and one hundred years

(obviously facts to be checked on the net later). On arrival we walked down the

very dark beach until we met wardens Kester and Becks. Kester had worked for the

last four years protecting his charges. Becks was on a one month stint awaiting

the start of her Law Degree Course at Edinburgh University - we wish her luck

for that. She told us that the most she had seen in one night was twenty seven

ladies, her busiest night, now the average is four as it is late in the

season.

We had to wait a while

while our lady got settled in to her dig, then we could approach. We were only

allowed to use red light torches as not to put off any other ladies that might

journey up the beach and to not confuse any babies en route to the sea, should

we be lucky enough for any hatchlings to chose tonight to begin their epic

struggle for life.

Our

lady was called WC (west Caribbean) 5573 as her tag read, Becks and

Kester recorded her statistics - she measured 1.83 metres (shell length) and

1.18 wide. Dora told me she was not a big leatherback by

any means. Becks and Kester on midwife

duty. They saw our lady was digging too close to another

nest so they filled in as she dug.

Once she began laying

Becks scooped her eggs into a bucket to put them

further away from the original nest. Our lady was now in a trance-like state so

we could stroke her. Being so close to this enormous creature from the deep was

truly a sensational and remarkable event in our lives. One we will never forget.

While this was going on another lady appeared out of the surf near us, she had

to be gently shooed along the beach. After our lady had finished we

watched her powerful front flippers pile the sand back for her rear

flippers to fill in the hole and neatly pat it down. I didn't care that I was

being eaten alive by mossies, even though I had thoroughly sprayed myself. Then

it sadly was time to walk back to the bus. As we slowly wandered we found where

the second lady had settled to her digging, she was left in peace as she was

nowhere near known nests. Twenty feet beyond her was lady number three. Becks

and Kester had their work cut out, no sooner than they had buried our bucket of

eggs they had to carry on their research on these other

ladies.

Now we were walking

even slower to the bus. Great excitement as we spotted a nest of hatchlings. Kester was now rushing between the

ladies and the babies, we were therefore allowed to use a red light to guide

them down the beach and watched in hope as the little ones faced the waves. We

didn't want to think odds at this time. We got back to Beez Neez at 01:30, too

excited to sleep, I got straight on line to research these amazing

creatures.

The Leatherback

Turtle

The leatherback turtle

- Dermochelys coriacea is the largest of all living sea turtles and the fourth largest modern

reptile behind three crocodilians. It is the only living

species in the genus Dermochelys. It can easily be

differentiated from other modern sea turtles by its lack of a bony

shell. Instead, its carapace is covered by skin and oily

flesh. Instead of teeth the Leatherback turtle has points on the

tomium of its upper lip. It also has backwards

spines in its throat to help it swallow food. Leatherback turtles can dive to

depths as great as 4,200 feet and they are considered to be critically

endangered by the World Conservation Union (IUCN).

Anatomy and

morphology:

Leatherback turtles follow the general sea

turtle body plan of having a large, dorsoventrally flattened, round body with

two pairs of very large flippers and a short tail. The leatherback's

flattened forelimbs are specially adapted for swimming in the open ocean. Claws

are noticeably absent from both pair of flippers. Leatherback front flippers can grow up to

two point seven metres in large specimens, the largest flippers (even in

comparison to its body) of any sea turtle. As the last surviving member of its family, the leatherback turtle has

several distinguishing characteristics that differentiate it from other sea

turtles. Its most notable feature is that it lacks the bony

carapace of the other

extant sea turtles. Instead of scutes, the leatherback's carapace is covered by its thick,

leathery skin with embedded minuscule bony plates. Seven distinct ridges arise

from the carapace, running from the anterior-to-posterior margin of the turtle's

back. The entire turtle's dorsal surface is colored dark grey to black with a sporadic scattering of

white blotches and spots. The turtle's underside is lightly coloured.

Dermochelys coriacea adults

average at around one to two metres long and weigh from around 250 to 700 kilograms. The largest ever found however was over three meters from head to tail

and weighed 916 kilograms. That particular specimen was found on a beach on the

west coast of Wales.

Physiology:

The metabolic rate of the leatherback is about four

times higher than one would expect for a reptile of its size; this, coupled with

counter-current heat exchanges, the insulation provided by its oily flesh and large body size, allow it

to maintain a body temperature as much as eighteen degrees

Centigrade above that

of the surrounding water. Its large size also gives the leatherback more

capacity to maintain its body temperature than smaller, more ectothermic

reptiles.

Leatherbacks are also the reptile world's

deepest-divers. Individuals have been discovered to be able to descend deeper

than 3,937 feet.

They are also the fastest reptiles on

record. The 1992 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records has the leatherback turtle listed as having achieved the speed

of 21.92

miles per hour in the

water.

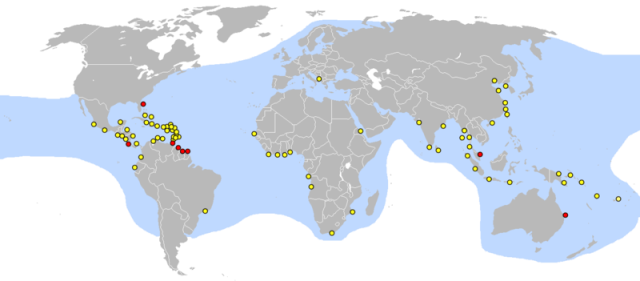

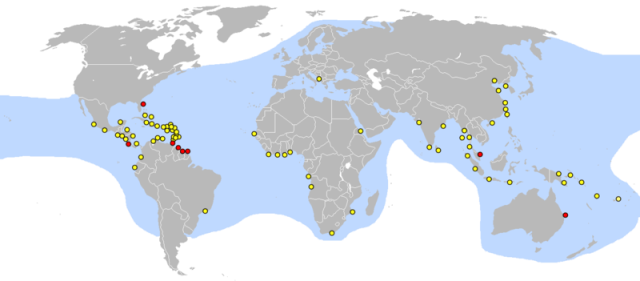

Distribution:

The leatherback turtle is a species with a

cosmopolitan global range. Of all the extant sea turtle species, Dermochelys coriacea has the

widest distribution, reaching as far north as Alaska and Norway and as far south as the Cape of Good Hope in Africa and the southernmost tip of New Zealand. The leatherback is found in all tropical and subtropical oceans, and its range has been known to extend well into the Arctic

Circle. Globally, there are three major, genetically-distinct populations. The

Atlantic Dermochelys population is separate from the ones in the Eastern and

Western Pacific, which are also distinct from each other. A third possible Pacific

subpopulation has been proposed, specifically the leatherback turtles nesting in

Malaysia. This subpopulation however, has almost been eradicated. The beach of

Rantau Abang in Terengganu, Malaysia, had once had the largest nesting

population in the world with 10,000 nests per year. However in 2008 only 2

leatherback turtles nested at Rantau Abang and unfortunately the eggs were

infertile. The major cause for the decline in the leatherback turtles is the

practice of egg collection in Malaysia. While specific nesting beaches have been

identified in the region, leatherback populations in the Indian

Ocean remain generally unassessed and unevaluated

Recent estimates of global nesting

populations indicate 26,000 to 43,000 nesting females annually, which is a

dramatic decline from the 115,000 estimated in 1980. These declining numbers

have contributed to conservation efforts to stabilise the leatherback sea

turtles and move their species away from the current status of critically

endangered. However, when we consider from hatchling to mature adult one in one

thousand survive, unless this number changes their status will remain

unchanged.

Global nesting

sites

Atlantic

subpopulation

The leatherback turtle population in the

Atlantic Ocean ranges almost all over the entire region. Their regional range spreads

as far north as the North Sea and south to the Cape of Good Hope. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherbacks' feeding areas are colder waters

where there is an abundance of their jellyfish prey which accounts for their more widespread range. However, only a few

select beaches on both sides of the Atlantic are utilised by the turtles as

nesting sites.

Off the Atlantic coast of Canada,

leatherback turtles can be found feeding as far north as Newfoundland and

Labrador. They have been sighted as far north as the Gulf of Saint Lawrence near

Quebec. The most significant nesting sites in the Atlantic are in Suriname,

French Guiana, Trinidad and Tobago and Grenada in the Caribbean and Gabon in Central Africa. The beaches of Mayumba National Park in Mayumba, Gabon are home to the largest nesting population of leatherback turtles on the

African continent. Off the northeastern coast of the South

American continent, a few select beaches between French Guiana and Suriname are

primary nesting sites of several species of sea turtles, the majority being

leatherbacks. A few hundred nest annually on the eastern coast of Florida. In

Costa Rica, the beaches of Parismina are known nesting grounds of leatherback turtles.

Pacific

subpopulation:

Leatherback turtles in the Pacific

Ocean have been determined to belong to two distinct

populations. One population is known to nest on beaches in Papua, Indonesia and the Solomon Islands while their foraging grounds are across the Pacific in the Northern

Hemisphere along the coast of Oregon in North America. The Eastern Pacific population forages in the Southern

Hemisphere, in waters along the western coast of South America while they nest in beaches on the Pacific side of Central

America, specific nesting grounds being in Mexico and Costa Rica. The Malaysian nesting population, reduced to less than a hundred individuals as of

2006, has been proposed as a third major Pacific subpopulation.

There are two major leatherback feeding

areas in the continental US. One well-studied area is just off the northwestern coast of the United

States near the mouth of the Columbian River These waters are excellent feeding grounds for the turtles, where they

are believed to be foraging in the nutrient-rich waters of the North Pacific.

The other American foraging area for the turtles is located in the state of

California. Further north, off the Pacific coast of Canada, leatherbacks have been seen on the

beaches of British Columbia.

Indian Ocean

subpopulation:

While little research has been done on

Dermochelys populations in the Indian Ocean, nesting populations are known from Sri Lanka and the Nicobar Islands.

Habitat:

Leatherback turtles can be found primarily

in the open ocean. Scientists tracked a leatherback turtle that swam from Indonesia to the

U.S. in an epic 13,000-mile journey over a period of 647 days as it searched for

food. The turtles prefer deep water but are most often seen within sight of

land. Feeding grounds have been determined to be closer to land, in waters

barely offshore. Unusually for a reptile, leatherbacks can survive and actively

swim in colder waters; individual turtles have been found in waters as cold as

4.5° Celsius.

The favoured breeding beaches of the

leatherback turtle are mainland sites facing deep water and they seem to avoid

those sites protected by coral reefs.

Life

history:

Like all sea turtles, leatherback turtles

start their lives as hatchlings bursting out from the sands of their nesting

beaches. Right after they hatch, the baby turtles are already in danger of

predation. Many are eaten by birds, crustaceans, other reptiles, and also people before they reach the water. Once they

reach the ocean they are generally not seen again until maturity. Very few

turtles survive this period to become adults. It is known that juvenile

Dermochelys spend a majority of their particular life stage in more tropical

waters than the adults.

Adult Dermochelys are prone to

long-distance bouts of migration. Migration in leatherback turtles occurs between the cold waters in

which mature leatherbacks cruise in to feed on the abundant masses of jellyfish

that occur in those waters, to the tropical and subtropical beaches in the

regions where they were hatched from. In the Atlantic, individual females tagged

in French Guiana off the coast of South America have been recaptured on the other side of the ocean in Morocco and

Spain.

Mating takes place at sea. Leatherback males never leave the water once they

enter it unlike females which crawl onto land to nest. After encountering a

female (who possibly exudes a pheromone to signal her reproductive status) a leatherback male uses head

movements, nuzzling, biting, or flipper movements to determine her

receptiveness. Females are known to mate every two to three years. However,

leatherbacks have been found to be capable of breeding and nesting annually.

Fertilisation is internal, and multiple males usually mate with a single female.

However, studies have shown that this process of polyandry in sea turtles does not provide the offspring with any special

advantages.

While the other species of sea turtles

almost-always return to the same beaches they hatched from, female leatherback turtles have been found to be

capable of switching to another beach within the same general region of their

"home" beach. Chosen nesting beaches are made of soft sand since their shells and plastrons are softer and easily damaged by hard rocks. Nesting beaches also have

shallower approach angles from the sea. This is a source of vulnerability for

the turtles because such beaches are easily eroded. Females excavate a nest

above the high-tide line with their flippers. One female may lay as many as nine

clutches in one breeding season. About nine days pass between nesting events. The

average clutch size of this particular species is around 110 eggs per nest, 85%

of which are viable. The female carefully back-fills the nest, disguising it

from predators scattering huge amounts of sand.

Cleavage of the cell begins within hours of fertilisation, but development is

suspended during the gastrulation period of movements and infoldings of embryonic cells, while the eggs are being laid. Development soon resumes, but the

embryos remain extremely susceptible to movement-induced mortality in their

nests until the membranes fully develop through the first 20 to 25 days of

incubation, when the structural differentiation of body and

organs soon

follows. The eggs hatch in about sixty to seventy days. As with other

reptiles, the ambient temperature of the nest determines the sex of the hatchlings. After nightfall, the hatchlings dig their way to the

surface and make their way to the sea.

As a global species with a range spanning

both hemispheres, leatherback nesting seasons vary from place-to-place. Nesting

occurs in February to July in Parismina, Costa Rica. Farther east in French Guiana, Dermochelys populations nest from March to August. Atlantic leatherback

turtles nest between February and July from South Carolina in the

US to the US Virgin

Islands in the

Caribbean and to Suriname and Guyana. With nearly 30,000 turtles visiting its beaches each year to April,

Mayumba National Park is the most important leatherback turtle nesting beach in Africa, and

possibly worldwide.

Evolutionary

history:

Leatherback turtles have been around in

some form since the first true sea turtles evolved over 110 million years ago

during the Cretaceous.

Etymology and

taxonomic history:

The species was first described in 1761 by

Domenico Vandelli as Testudo coriacea. In 1816, the genus Dermochelys was coined by the French zoologist Henri

Blainville. The leatherback was then reclassified under this own genus as

Dermochelys coriacea.

Aside from

"leatherback" turtle, it has been called the "leathery turtle" in the past. The

turtle was also once referred to as the "trunk" turtle, though the name is now

in disuse.

Importance to

humans:

The harvesting of sea turtle eggs is still

practiced by people around the world. Asian exploitation of the turtle's nests have been cited as the most

significant factor for the species' global population decline. In Southeast

Asia, the collection of leatherback eggs has led to a near-total collapse of

local nesting populations in specific countries like Thailand and Malaysia. Specifically in Malaysia, where the turtle is practically locally

extinct, the eggs are considered a delicacy. In the Caribbean, some cultures

consider the eggs of sea turtles to be aphrodisiacs.