Denison Canal

|

The Denison Canal  Our first picture together in

Tasmania just happened to be at our first stop in Mabel at the Denison

Canal, the only purpose-built sea canal in Australia. The only other canal in

Tasmania was the unsuccessful Lauderdale (Ralphs Bay) Canal which failed due to

siltation. A proposal for a canal through Eaglehawk Neck was rejected for the

same reason. The siltation problem does not occur in the Denison Canal because

of the absence of surf; and because a difference in tide times at Blackman Bay

and Norfolk Bay creates currents that scour out any sand

deposits.  Why was the canal built: Records in

1815 and 1821 describe boats being dragged across East Bay Neck – perhaps using

round spars as rollers. In the 1840’s, convicts built a wooden railway with a

truck for carrying boats. Isolated settlers on the East Coast had no connecting roads to

their markets in Hobart. They were dependent upon sea transport, involving a

long and sometimes difficult passage around Tasman Peninsula. They were the

first to pressure the government for a canal to link Blackman Bay to Norfolk

Bay. Lieutenant Governor William Denison requested a report

in 1854, but the idea lapsed with his transfer to New South Wales. There was a

further attempt in 1866, but Parliament rejected the legislation. Finally, in

1900, government decided to proceed, and tenders were called in June 1901, the firm Henrikson and Knutson were selected after lodging the lowest

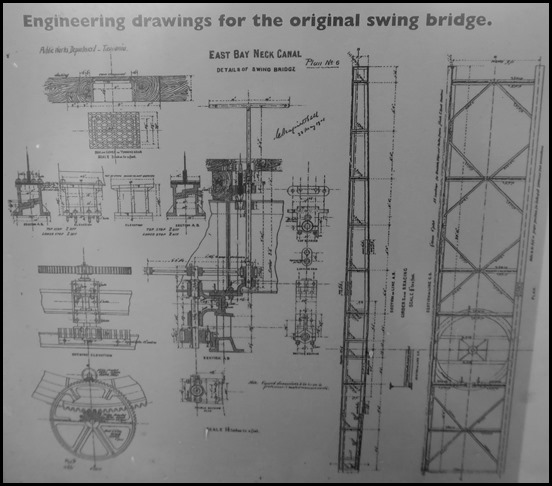

price (£17,999). The canal was designed by Napier

Bell. While the contract specified that the

canal was to be completed by the 29th of May 1904, the start of work on the

project was delayed by negotiations over whether Henrikson and Knutson or the

Tasmanian Government would retain ownership of the equipment needed to build the

canal once it was complete. The canal was finally opened by Governor

Sir

Gerald Strickland on the 13th of October 1905.

At this time it was reported to be the second-longest canal in Australia. The

Denison Canal was bridged by a hand-operated swing bridge until 1965, when a

larger and electrically operated bridge was installed. It is common for Sydney–Hobart yacht

racers returning to Sydney to use the canal as a convenient

shortcut.     How was the canal built: Preliminary work, such

as building replacement roads and diverting a creek, started in March 1902.

Full-scale excavation began on the 12th of April.

The

soil was first loosened by a plough pulled by a team of bullocks. It was then

shovelled by gangs of men into side-tip railway wagons on temporary rails.The

wagons were hauled by a small Krauss 8-ton locomotive

to dump sites at either end of the canal. The engine and wagons were brought

from a West Coast railway company and on completion of their work, were sold to

the Sandfly Colliery Co. They were sold on to the Catamaran Coal Co. in about

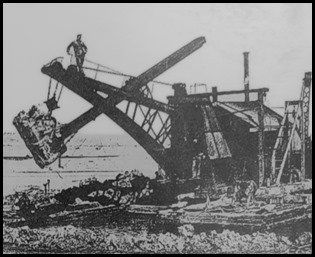

1912.   Excavated Material: Dredging produced about 37,500 cubic metres of material from the two approach channels. The dredged approach channel in Norfolk Bay is nearly a kilometre long, and the Blackman Bay channel is over half a kilometre long. A steam shovel floating on a barge (acting as a dredge), carried out the final deepening, and completed channels into either bay. The dredge was bought from the Brisels tin mine in Derby, north east Tasmania. It was partially dismantled and brought by rail to Hobart.

Characteristics: The Denison Canal is 895 metres (2,936 feet) long, or 2.42 kilometres (1.50 miles) long if its dredged approaches are included. It is 34 metres (112 feet) wide at ground level, dropping to 7 metres (23 feet) at low tide. Water depth varies from 3.9 metres (13 feet) at high tide to 2.6 metres (8.5 feet) at low tide. While the canal was once able to be used by small trading vessels, only small fishing and recreation boats can now pass through the shifting sand bars in Blackman Bay on the eastern approaches to the canal.

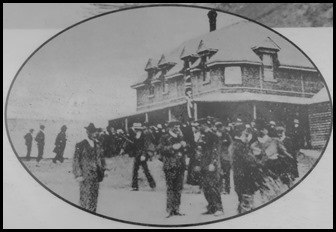

Completion: Construction was virtually complete and the canal was in use by March 1905. In the month prior to the official opening one hundred and four vessels passed through. The Governor – Sir Gerald Strickland, performed the official opening on the 13th of October 1905. The S.S. Dover was chartered to bring from Hobart the party of seventy people. A luncheon banquet in a marquee at the Dunalley Hotel was provided by the Wardens of Sorell, Spring Bay and Glamorgan municipalities. In the afternoon, the Governor declared the canal open and announced the name – Denison Canal.

Dunalley Hotel 1866-1891. The hotel was rebuilt in 1892 after a fire. The hotel today.

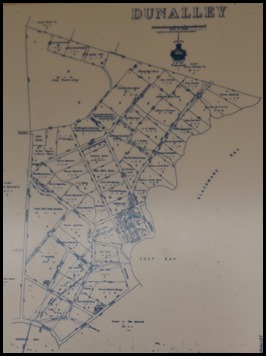

While the penitentiary was in operation at Port Arthur (1830 to 1877), there was a prohibition on private ownership of land on Forestier and Tasman peninsulas. The exceptions included Captain Spotswood and Dr Imlay. Only military personnel were allowed in the area without a special pass. There was a military presence on East Bay Neck at Dunalley prior to a station being established at Eaglehawk Neck. Hence, land development did not occur south of Dunalley until after 1877. Dunalley is a small fishing village nearby, part of the Sorell Council. At the 2006 census, Dunalley had a population of 313. Dunalley is approximately 57 km (35 miles) east of Hobart on the Arthur Highway and twenty minutes from Sorell. It is located on the narrow isthmus which separates the Forestier and Tasman Peninsulas from the rest of Tasmania. Dunalley was first named East Bay Neck but was renamed Dunalley after Henry Prittie, 3rd Baron Dunalley (1807-185). Dunalley came from Kilboy in the County of Tipperary, Ireland. The name is thought to have been given by Captain Benjamin Bayly to his nearby farm on his retirement from the army in about 1838. Baron Dunalley is said to have procured a commission for him in his regiment, so the name was chosen in gratitude to his benefactor. Township blocks were offered for sale in about 1842; from that time, the name Dunalley was used. The growth of the township was very slow. The ‘Tasmanian Gazetteer’ for 1877 recorded that Dunalley consisted of one hotel and ten houses. About eleven kilometres from Dunalley is Swan Lagoon, emptying into North Bay.

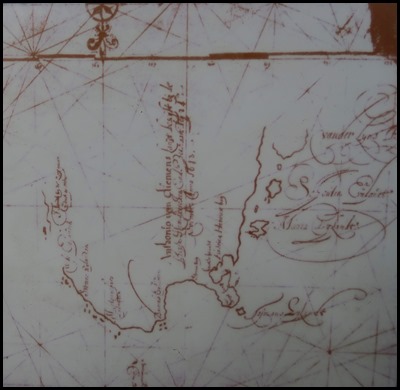

Blackman Bay is the place where Tasman’s crew made their second landing (on the 3rd of December 1642). Gilseman’s map drawn in 1642 – the oldest original Tasmanian map in existence, not published until 1932. By showing the place where water was collected, it upset all previous suppositions about the first landings. It is part of the ‘Lagoon Bay’ property originally developed by Dr Imlay who had cattleraising interests in Twofold Bay, Eden in New South Wales. The first scientific study of the area was undertaken by the French expedition under Nicolas Baudin in the ships Geographe and Naturaliste. Of the twenty three scientists who commenced the voyage in 1800, only three were still with the ships when they returned to France in 1804, many having died overseas. Dr Imlay had the contract to supply fresh meat to the Port Arthur establishment. His cattle were shipped to Lagoon Bay where they swam ashore, fattened for a time, and then taken south to Flinders Bay (Murdunna) where the slaughterhouse was maintained. The Lagoon Bay farm is now part of a much larger holding called ‘Bangor’ which is farmed on ecological principles by the Dunbabin family.

‘Cheapest in Dunalley’ Long’s shop circa 1910.

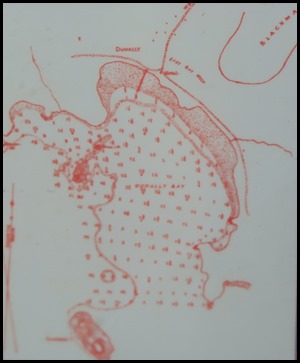

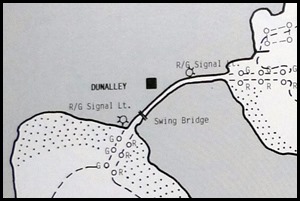

Chart from the engineering report – depth soundings for the western approach to the Denison Canal. Dunalley for sailors – showing the green and red markers. Rooganah was a hundred ton centre board schooner built by John Wilson in 1909. She is seen here impressively sailing through the Denison Canal, a tricky and difficult task.

Town plan 1942. Oyster

leases.

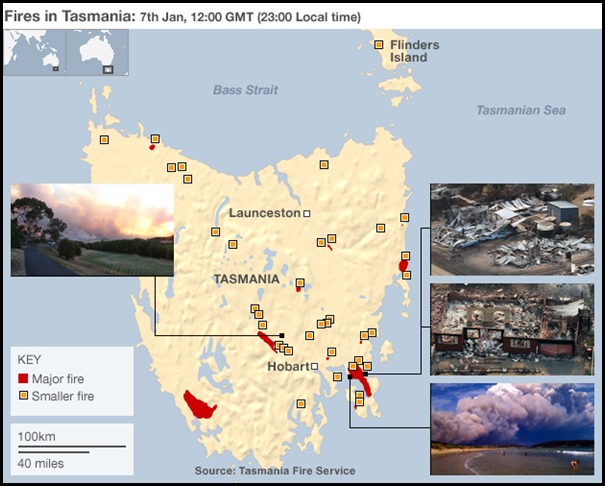

Dunalley (the three pictures – bottom right of the Fire Service image above) was badly affected by bushfires on the 4th of January 2013, with the town losing about sixty five structures, including the Police Station, primary school, bakery and local residences.

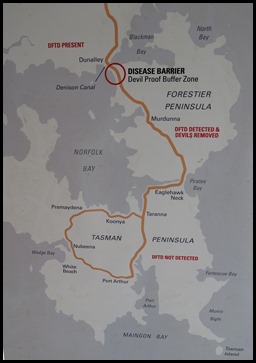

The last information boards for to read was all about the Tasmanian devil. The Tasman and Forestier peninsulas are an important habitat area for the Tasmanian devil. The area is a refuge for an isolated population of healthy devils living in the wild, free from the deadly Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) which is threatening the species across the rest of Tasmania. The Peninsula Devil Conservation Project is boosting this population with the reintroduction of more healthy devils and undertaking a range of measures to stop the movement of potentially diseased devils on to these peninsulas.

The peninsulas are separated from mainland Tasmania at two points: the Forestier Peninsula by the Denison Canal at Dunalley, and then the Tasman Peninsula by the narrow isthmus at Eaglehawk Neck. This separation resists animal movement into and out of these areas, helping to maintain an isolated and healthy devil population. The areas have ideal devil habitat, large enough for a self-sustaining population of healthy devils. The Tasman Peninsula is doubly isolated with the buffer of the Forestier Peninsula between it and the rest of mainland Tasmania. Past surveys and control measures: Tasmanian devils have always lived on these peninsulas but their numbers have fluctuated since European settlement. Before DFTD, the devil population was estimated to be around two hundred and fifty, with most devils living on the Forestier Peninsula. In 2004 devils on this peninsula were detected with DFTD and in the following years an attempt was made to halt the spread of the disease by removing all infected devils. In 2012 a decision was made to remove all remaining devils to ensure the area was DFTD-free. The disease has not spread to the more isolated devils on the Tasman Peninsula, which according to recent surveys are slowly increasing in number. Rewilding and protecting: The plan is now to boost the numbers of devils on the peninsulas by introducing healthy offspring from those devils removed from the Forestier Peninsula in 2012. Devils can swim, climb, dig and run long distances in pursuit of food and a mate. The challenge ahead is to stop the movement of diseased devils onto the peninsulas, protecting the healthy populations and their future. The canal before the Forestier Peninsula is the first barrier with its deep water and strong current. A range of measures to prevent any future re-entry of potentially infected devils include:

We wish the devils ‘good luck’ and

hope they continue to increase in number, it would be a terrible shame to lose

them.

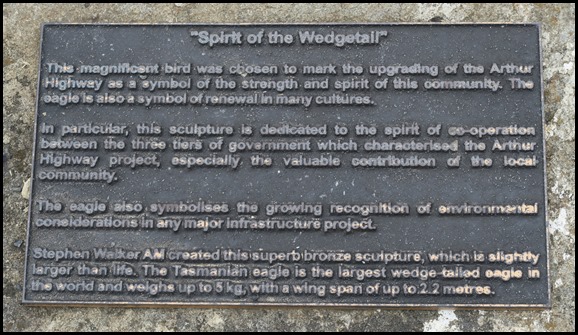

Admiring the wedgetail.

With a quick look back at the Denison Canal, it was time to get back on the road and follow the sign for Port Arthur.

ALL IN ALL A GREAT FIRST STOP TO OUR MABEL AT-VENTURE CLEARLY THERE IS MUCH TO EXPLORE, MORE THAN I HAD APPRECIATED |