Guy Menzies

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 30 Aug 2014 22:47

|

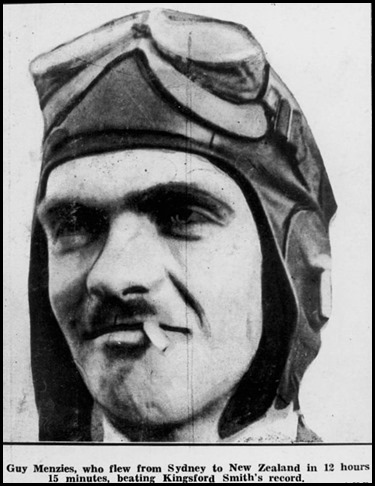

Guy Lambton Menzies

We left State

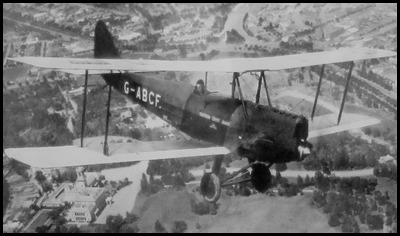

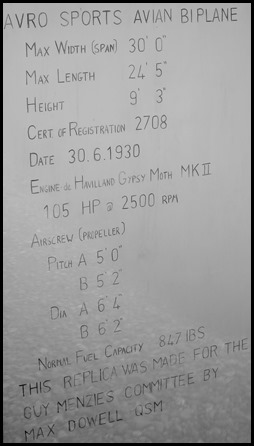

Highway 6 before Harihari and drove six or seven miles to see the replica of Guy Menzies plane. Guy Menzies completed the first solo

crossing of the Tasman Sea on January 1931. He landed his single engine Avro

Avian plane, Southern

Cross Junior, in the La Fontaine swamp near Harihari, mistaking it

for a grassy paddock. The plane tipped over, an ignominious end to a

record-breaking flight, Guy had crossed the west coast of the

South Island near Ōkārito after eleven hours and forty

five minutes. Initially, local residents refused to

believe that he had flown across the Tasman Sea, and were only convinced when he

produced a sandwich bag from Sydney airport.

The landing spot

near Harihari is marked by a memorial. The swamp has been drained, and now

actually is a grassy

paddock.

At the end of the

road we saw a paddock and crossed

a bridge.

Just over the

bridge was the memorial to Guy Menzies with a very smart plaque, not a replica in

sight.

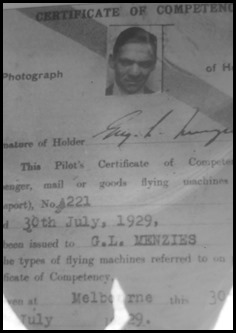

The Pilot: Guy Lambton Menzies was born on the 20th of August 1909,

the eldest of five children of Dr and Mrs Guy Menzies of Sydney. A high spirited

boy, he was intently interested in all things mechanical – the faster and

noisier the better. He did not excel at school and left at the age of sixteen.

During his teenage years he raced a motorcycle on Sydney speed tracks as Don

McKay, the Flying Scotsman, to conceal the activity from his parents. An

accident forced a change – to flying. Initially irresponsible, Guy continued

taking lessons with the Aero Club of New South Wales and by 1930 was an

accomplished and experienced aviator.

The first crossing of the Tasman by air had been achieved on the 10th

and 11th of September 1928 by Charles Kingsford

Smith and Charles

Ulm in the Southern

Cross, Charles Smith had also flown the plane from England to

Australia. Determined to fly the

Tasman, Guy with his new business partner Albert James, bought the Avro Sports

Avian biplane ‘Southern Cross Junior.

Guy spent hours studying aerial navigation, as

radio and navigational aids were still in their early development. For

direction, a bearing would need to be established between Sydney and some point

in New Zealand, then this bearing maintained by compass, making allowance for

drift either way, by cross winds. Ground speed had to estimated by adding or

subtracting head or tail winds to air speed. The only means of calculating wind

velocity and direction would be the pattern and height of the waves. No life

raft was carried on the flight. A solo bid non-stop from Perth to Sydney was

indicated so that night flying practice, maximum quantities

of fuel, eighteen hours flying time, and other preparations would not seem out

of place. After meticulous planning including equipment testing, meteorological

forecasts and learning stress reducing techniques, Guy was

ready.

A map of New Zealand could not be procured without

raising suspicion so Guy visited the New Zealand Government office in Sydney and

charmed an office worker who provided detailed maps and kept her promise of

secrecy. After much study, Guy chose Blenheim as his destination. Having only

taken delivery of the Avro Avian on Christmas Eve 1930, he spent the next

fortnight familiarising himself with the plane, and installing a second compass.

Guy wanted to make the flight as soon as possible to

take advantage of the short nights, so the decision was taken to leave on the

7th of January 1931. At Mascot Airport he bade farewell to seven friends and

family and the Controller of Aviation.

The Flight: Despite

fitting an extra fuel tank that gave the Avian eighteen hours endurance, Guy

realised he was unlikely to get approval for an over-water record attempt. He

kept his plans to himself, indicating instead that he was going for the

Sydney-Perth record. At 1am on the 7th of January 1931, Guy took off from Mascot

Aerodrome and headed east, not west. When opening their sealed envelopes, his

friends learned of his real destination.

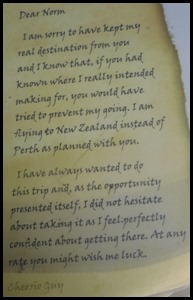

One of them

read:- Dear Norm, I am sorry to have kept my real destination from

you and know that, if you had known where I really intended making for, you

would have tried to prevent my going. I am flying to New Zealand instead of

Perth as planned with you. I have always wanted

to do this trip and, as the opportunity presented itself, I did not hesitate

about taking it as I feel perfectly confident about getting there. At any rate

you might wish me luck. Cheerio Guy.

The

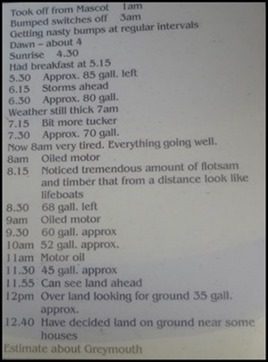

flight started in calm conditions, Guy saw the lights of Sydney fade

behind him as he headed east. After an hour or so he felt the first of an

easterly wind. This increased until he was being buffeted by squalls. Guy would estimate his

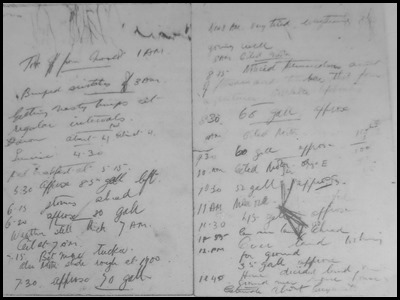

fuel reserves at half past each hour, jotting his results

down, and on the hour would pump more oil into the engine from an

auxiliary tank. The first big squall caused him to knock the ignition switch and

stall the plane. With discipline he went through his cockpit drill and rectified

the problem, gradually coaxing the plane back to cruising level. By 4am he was

beginning to feel fatigued. At 5:15 the wind had backed around to the north-west

and instinct told Guy he was being blown to the south but he resolutely stuck

with his planned bearing. He calculated at six that he had eighty gallons of

fuel, in theory enough for another ten hours flying. An hour later Guy

encountered a storm, causing his plane to rock and lurch violently. He fought

for control. Trying to fly above the bad weather at eleven thousand feet proved

too cold so he was forced to fly under the cloud and at one stage nearly hit the

sea, actually tasting salt...... The planes only blind flying aids were an

altimeter and a simple turn-and-bank indicator.

At eight in the morning with an estimated seventy gallons of fuel

left Guy noticed logs floating in the sea. At eleven o’clock as he flew between

three and five hundred feet, the weather became atrocious and Guy was flying

blind with huge tail winds. He estimated that with the help of these winds, he

should make landfall at any time. By 11:30 there was no sign of land and only

forty five gallons of fuel remained. Another tortuous hour passed before the

horizon darkened and eventually showed itself to be the land he had so longed to

see. Guy had made landfall on the southern West Coast close to Gillespie’s

Beach, a former goldmining settlement of the 1860’s. Only two people had lived

there since the mid 1920’s, brothers Ted and Bill Bagley who prospected for gold

in the black sands. On the 7th of January Ted was taking his turn ‘to go on the

medicine’ after the gold specks had accumulated. Riding with a packhorse to

Weheka – Fox Glacier, for supplies. He would then travel on to Hokitika to have

a high time before returning. At home, Bill heard a plane circling, looking up

he saw Guy fifty feet above the ground. Guy shouted “I want to land”. Bill

shouted back directions to a landing strip at Weheka but these were lost in the

engine noise. He pointed inland and Guy headed that way. However, thick weather

hid the mountain peaks, and having no wish to encounter them, he flew back up

the coast into the rain.for

“It was the fog and cloud

enshrouding the Southern Alps which prevented me going on to Christchurch. I

could not see very far, and did not know whether the mountains were two or

twelve thousand feet high. I could not take a risk, so I looked for the nearest

landing ground.”

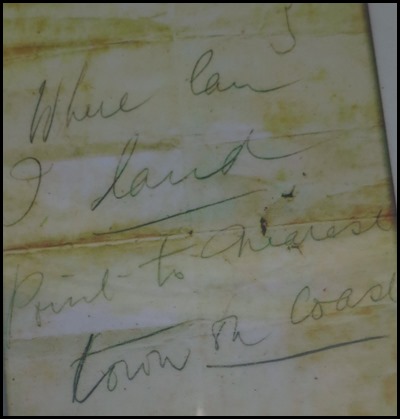

Flying above the seaside settlement of Ōkārito and

seeing people below, Guy scribbled a note, crammed it

in a bottle and threw it out. It was found many months later by Charlie Black

who was cutting gorse near the lagoon. The bottle broke but the note is kept at

the West Coast Historical Museum, Hokitika. With the tide in at Ōkārito and no clear paddocks, Guy continued north.

Turning inland at the Big Wanganui River mouth, now running short of

fuel.

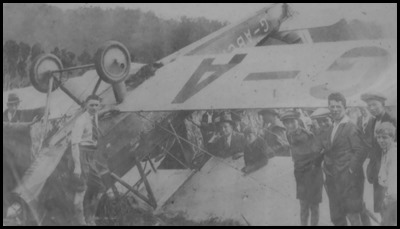

The Landing: Guy spotted what looked like pasture, not until nearly

down did flax bushes loom into view. “Near Hari Hari I spotted what looked

the goods and went down. My pick was bad, for the ground turned out to be soft

and marshy but it was too late to worry. The wheels went in, and the machine

stopped dead and then stood up on its beak.” Uninjured, Guy undid

his harness and dropped out of the cockpit. He then tried to make his

way to one of the farmhouses he had seen from the air, soon a local, Jack Hewer

demanded, “who the bloody hell are you ?” The young pilot explained he had just

flown from Australia but Jack wouldn’t

believe him until he saw the

plane.

Some other locals were quickly on the scene, Alf

Wall who owned the farm where the plane ‘landed’, Gordon Mitchell and Jack

Searle – neighbouring farmers. Bert Kelly owner of the cream collection truck

who had seen the plane flying too low and feared the worst. Mrs Minnie Wall,

Alf’s wife, who had an endearing way of climbing on her roof for “a look around”

also saw the plane circling the area. Bill Berry Senior with his friends Bill

and Vic, witnessed the Avro Avian descent, these people quickly crossed streams

and farmland to make their way to the plane about a mile away.

Alf Wall took Guy to a local homestead where

afternoon tea was provided for everyone. A telephone call was made to the local

shopkeeper and postmaster George Rowley, to tell him of the flight and landing.

Following afternoon tea with the incredulous Harihari farmers, Guy was

eventually driven to the small telephone exchange in order to telegraph his

parents. Fifteen year old Marjorie Rowley sent it. Guy was driven in triumph to

Ross.

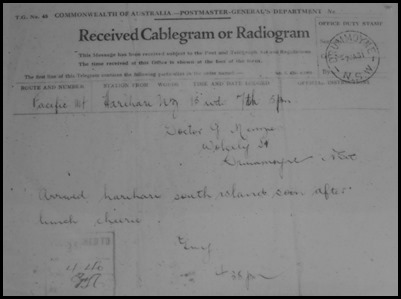

News of his flight was telegraphed around New Zealand and

Australia, the cablegram to his father was sent at

4.35pm and was delivered to Drummoyne, Sydney at 5.00pm, the message read:

Arrive Harihari south Island soon after lunch. Cheerio Guy.

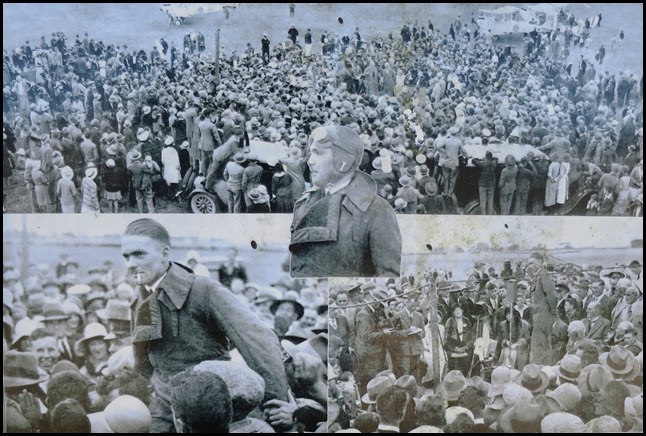

News spread and many made there way to the

‘landing’ site to be involved in this story in aviation history,

eventually Southern Cross was righted.

The locals helped load the plane onto a horse

and cart, driven by the capable hands of Mr Jock Adamson who crossed the

fields to the nearest road. One of Newman’s trucks

was waiting at the road to transport the plane to Hokitika where it would travel

by rail to Wigram Air Base for repair.

The hero was feted by delighted West

Coasters, Guy was soon joined by Albert James, his business partner and they set

off on a flying tour of the Dominion.

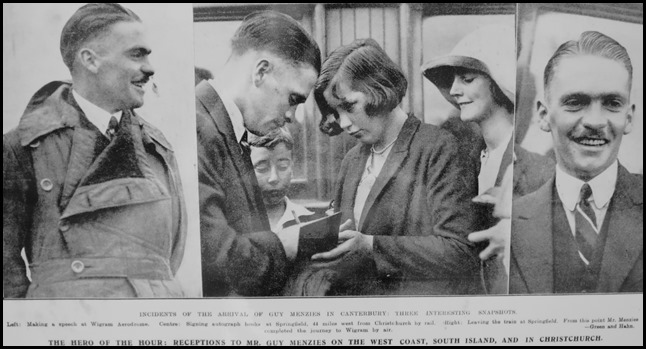

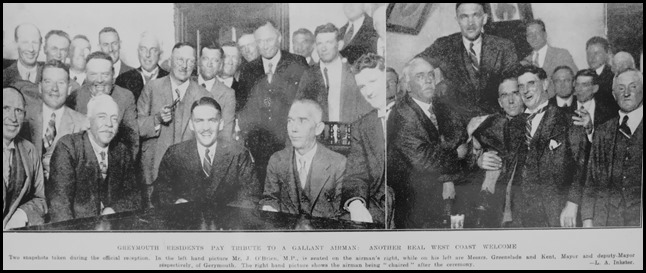

Greymouth reception.

West Coast hospitality and ringing home

The hero.

After the

Flight: Guy Menzies returned to a civic reception in Sydney where he

was awarded Freedom of the City. He and Albert James dissolved their business

partnership, with Albert retaining ownership of the Southern Cross. He

was killed a few weeks later when the plane crashed at Mascot. Guy Menzies’

piloting skills secured him a commission in the Royal Air Force. During the

1930’s he served with 23 Fighter Squadron in England. 205 Flying Boat in

Singapore, and 56 Fighter Squadron and 114 Bomber Squadron in the UK. Just

before World War Two broke out he went to 228 Squadron of Coastal Command and

Sunderland Flying Boats.

Squadron Leader Menzies served in the Meditteranean until he was killed on the

1st of November 1940 when his Sunderland was shot down by Italian Air Force

Fighters off the east coast of Sicily whilst flying from Malta. No remains of the aircraft or crew

were ever found. He is

commemorated at the Alamein

Memorial in Egypt.

On the 7th

January 2006, celebrations were held in Harihari to commemorate the 75th

anniversary of Menzies' trans-Tasman voyage, and were marked by a re-enactment

of the flight by adventurer Dick

Smith.

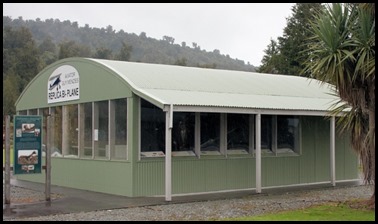

We left the memorial, drove back toward Harihari, once on the main road we passed a few

shops, then, the building that houses Guy

Menzies Replica.

Sadly, the

building was locked and in the bright sun pictures through the glass were

limited. The best

two.

ALL IN ALL LOST TOO YOUNG A DARING AND BRAVE MAVERICK |