Castle Howard Dome

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Fri 9 May 2014 22:17

|

The Dome of Castle Howard

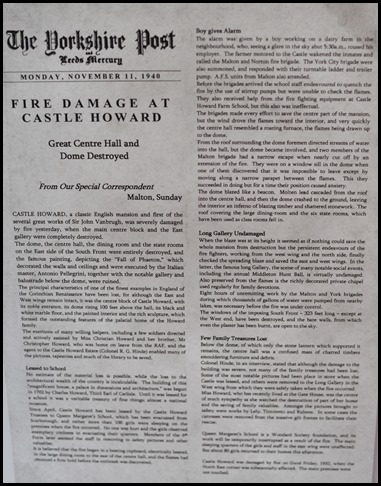

On Monday the 11th of November 1940,

the Yorkshire Post featured the sad story of a fire at

Castle Howard.

Before and

after the fire.

The underside of the dome is

decorated with the story of the Fall of Phaeton, painted by Pellegrini from

1709-12. It depicts the moment when Apollo’s son, Phaeton, stole his father’s

sun chariot and rode it across the skies. Unable to curb the horses he spun out

of control and tumbled to earth in a fiery blaze. Little did anyone realise that

one day this story would literally come true when the dome crashed into the hall in the fire of 1940. During the war Castle Howard was used as a school, it is believed the

fire began in the chimney of the servants kitchen.

Many things at Castle Howard seem to

happen twice including building of the great central dome. Between 1699 and 1700

Vanbrugh persuaded the 3rd Earl of Carlisle to ornate his new mansion with an

enormous masonry lantern and cupola, which gave Castle Howard a highly

distinctive profile: no other private home in England can boast such an

architectural feature. Completed in 1707, the dome remained the majestic

crowning point of Castle Howard until the calamity of 1940, when it crashed into

the house leaving a tangle of molten lead, charred timber and damaged

stonework.

For the next twenty years Castle

Howard remained a home without a dome until in 1960 Professor E.H. Thompson from

the University of London undertook the challenging task of working out the exact size and scale of Vanbrugh’s dome. Because no

original drawings existed the dimensions had to be arrived at through the

technique of photogrammetry using early, pre-fire photographs of the

house.

Vanbrugh might not have understood

the algebraic calculations and complicated pieces of machinery Thompson and his

team employed but he would have recognised how these were a means to an end –

namely a faithful reconstruction of his great dome.

Both Sir John

Vanbrugh and Professor Edward Palmer Thompson

were men of multiple interests and talents. Vanbrugh was a London trader, a

merchant in India, a soldier, a civil servant, a dramatist and theatre

impresario, a knight of the realm and an architect. Thompson was also a soldier,

as well as a mechanical student, scholar, inventor, teacher and connoisseur of

the arts. They also share the unique satisfaction of having built the dome at

Castle Howard.

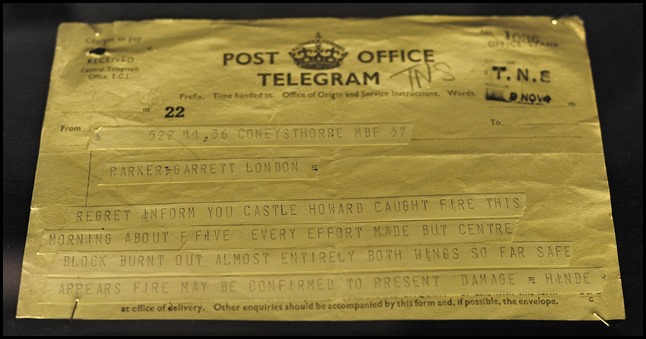

The

telegram from Colonel Hinde, the Agent, informing the Trustees that

Castle Howard had caught fire.

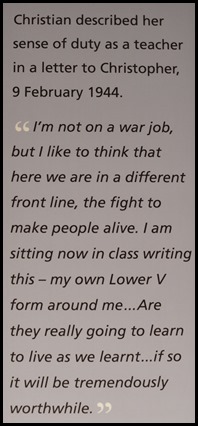

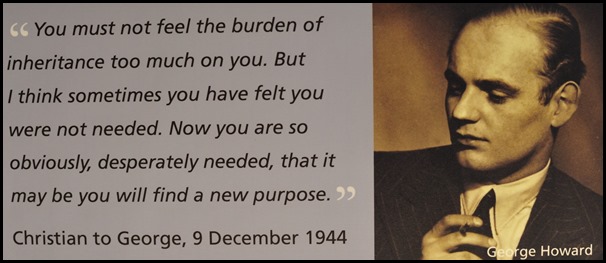

Christian

was a great support to her brother, George, during

this awful time.

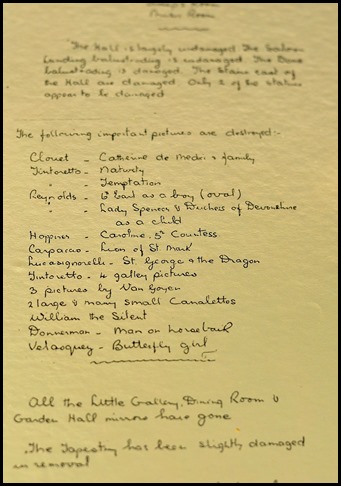

The handwritten

list of some of the important art losses.

In total some twenty rooms were lost,

some with delightful name such as the Kit Cat Room, the Jasmine Room, the

Queen’s Room, the Bullseye Rooms and the Canaletto Room. Nearly one third of the

building was left open to the skies, and although in time the debris would be

cleared and the structure made secure there was no escaping the fact that Castle

Howard had been substantially damaged by the fire. In time these areas would

receive a temporary roof and new windows, but it would be another twenty years

before major restoration began.

The biggest architectural loss was

obviously the dome, to imagine the house without would be to see an ocean-going

vessel without its funnels. The proportion and grandeur of the house are

entirely lost, and the Central Block assumes a strangely stunted

appearance.

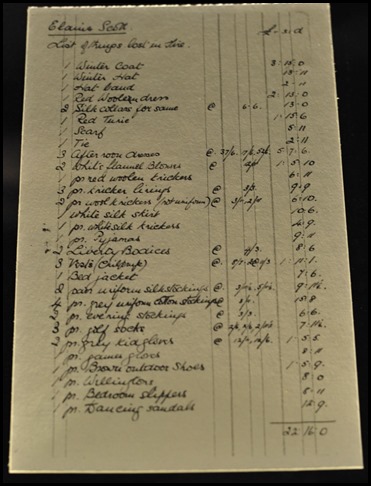

Pupil Elaine

Scott’s list of all she lost in the fire.

Each side of the Great Hall the staircases show fire damage to

this day.

The blackened

ceiling. The scorched paint. The charred stone next to the newer wooden floor.

Further along the upper corridor we

entered rooms not yet renovated.

The dome

today.

In 1962 Scott Medd, a Canadian

artist, was commissioned to reconstruct Pellegrini’s masterpiece – The Fall

of Phaeton. He only had a single black and white photograph of the original

painting to work from, but with careful research into colour and design, and by

examining other examples of Pellegrini’s work, Medd was able to reproduce this

celebrated episode from classical legend fully in the spirit of his Venetian

predecessor. The finished design was scaled up from smaller models and

eventually Medd perched on a scaffold tower, seventy feet high to execute this

dramatic tale.

ALL IN ALL REALLY

INTERESTING

CHUFFED THIS UNIQUE STRUCTURE IS AS IT SHOULD

BE |