|

The

Fastest

Well it seemed fitting after the

biggest to find out the fastest.

4000 years of naval construction, how

much has been gained in speed?

From ancient times until the 19th

century, the most efficient way of moving men and materials over great distances

was by sea. It was much more economical than transport by foot, cart, camel

caravan and was often safer too. Until the arrival of the airplane, it was also

the speediest way, as can be seen by these crossing times:

Sailing

ships:

-

1846 -

Yorkshire

left Liverpool for New

York crossed in 16

days

average speed 8.0 knots

-

1851 - Flying

Cloud left New

York for San Francisco crossed

in 89

days average

speed 7.1 knots via Cape Horn.

-

1853 - Northern Light left San Francisco for

Boston

crossed in 76

days

average speed 8.3 knots

-

1868 -

Thermopylae left

Liverpool for

Melbourne crossed in 63

days

average speed 8.0 knots

-

1905 -

Atlantic

left Sandy Hook for

England crossed

in 12 days 4 hours average speed 10.3 knots

Steamships:

-

1838 - Great

Western left

Bristol

for New York crossed in

15

days

average speed 7.8 knots

-

1934 -

Bremen left

Cherbourg for Ambrose Light

crossed in 4 days 14 hours average speed 28.0 knots

-

1937 -

Normandie left New

York for

Southampton crossed in 3 days 22 hours average speed 31.4

knots

-

1938 - Queen

Mary left Ambrose Light for Bishop's

Rock crossed in 3 days 20 hours average speed 34.0

knots

-

1952 - United

States left Ambrose Light for Bishop's Rock

crossed in 3 days 10 hours average speed 35.8 knots

The Flying Cloud of 1851 was the most famous of the

extreme clippers built by Donald McKay in East Boston, Massachusetts, intended for Enoch Train of

Boston, who paid $50,000 for her construction. The Flying

Cloud was purchased at launching by Grinnell, Minturn &

Co., of New York, for $90,000,

which represented a huge profit for Train & Co. Within six weeks she sailed

from New York and made San

Francisco 'round Cape

Horn in 89

days, 21

hours under the command of Captain

Josiah Perkins Creesy. In the early days of the California Gold Rush, it took more than

200 days for a ship to travel from New York to San Francisco, a voyage of more

than 16,000 miles. On the 31st of

July, during the trip, she made 374 miles in 24 hours. In 1853 she beat

her own record by 13 hours, a world beating record that stood for 136 years,

until 1989 when the breakthrough-designed sailboat Thursday's Child

completed the passage in 80 days, 20 hours. The record was once again broken

2008 by the French racing yacht Gitana 13 with a time of 43 days and 38

minutes.

The Flying Cloud's achievement was remarkable under any

terms. But, was all the more unusual because her navigator was a woman, Eleanor

Creesy, who had been studying oceanic currents, weather phenomena, and

astronomy since her girlhood in Marblehead,

Massachusetts. She was one of the first navigators to exploit the

insights of Matthew Fontaine Maury, most notably the course

recommended in his Sailing Directions. With her husband, ship captain Josiah

Perkins Creesy, she logged many thousands of miles on the ocean,

traveling around the world carrying passengers and goods. In the wake of their

record-setting transit from New York to California, Eleanor and Josiah became

instant celebrities. But their fame was short-lived and their story quickly

forgotten. Josiah died in 1871 and Eleanor lived far from the sea until her

death in 1900.

The Flying Cloud

The Cutty Sark is the most famous British Clipper . Built in

1869, she served as a merchant vessel (the last clipper to be

built for that purpose), and then as a training ship until being put on public

display in 1954. She is preserved in dry dock in Greenwich,

London. However, the ship was

badly damaged in a fire on the 21st of May 2007

while undergoing extensive restoration. The Cutty Sark is the only remaining

original Clipper ship from the 1800's.

Etymology: The ship is named after the Cutty

Sark (Scottish for

short

chemise or

undergarment). This was the nickname

of the fictional character Nannie Dee (also the name of the ship's

figurehead) in Robert

Burns' 1791 comic poem Tam O'

Shanter. She was wearing a

linen cutty sark that she had

been given as a child, therefore it was far too small for her. The

erotic sight of her dancing in

such a short undergarment caused Tam to cry out "Weel done, Cutty-sark", which

subsequently became a well known idiom.

Her Portuguese nickname was Pequena Camisola - Portuguese for Little

Shirt

History: She

was designed by Hercules Linton and built in 1869 at

Dumbarton, Scotland, by the firm of Scott

& Linton, for Captain John "Jock"

"White Hat" Willis; Cutty Sark was launched

on November the 22nd of that year, and after

Scott & Linton was liquidated she was

completed by William Denny & Brothers for John Willis &

Son. Cutty Sark was destined for the tea

trade, then an intensely competitive race across the globe from China to

London, with immense profits to

the ship to arrive with the first tea of the year. However,

she did not distinguish herself; in the most famous race, against

Thermopylae in 1872, both ships left

Shanghai together on June the

18th, but two weeks later Cutty Sark

lost her rudder after passing through

the Sunda Strait, and arrived in London

on October the 18th, a week after

Thermopylae, a total passage of 122 days. Her legendary reputation is supported

by the fact that her captain chose to continue this

race with an improvised rudder instead of putting into

port for a replacement, yet

was only beaten by one week.

Career (UK,

Portugal)

-

Names:

Cutty Sark 1869-1895, Ferreira 1895-1916, Maria do Amparo 1916-1922, Cutty

Sark 1922 to date.

Tonnage:

975 GRT

-

Namesake:

Scottish witch Cutty

Sark

Displacement: 2,100 tons at 20 ft

draught

-

Christened:

The 22nd of November 1869 by Mrs.

Moodie.

Length:

212 ft

-

Acquired:

British Merchant

Navy

Beam:

36 ft

-

Commissioned: The 16th of

February

1870

Speed:

17.15 knots

-

Out of Service: December

1954 Capacity:

1,700 tons

-

Homeports:

London 1870-1895 Lisbon 1895-1911 Lisbon 1911-1923 Falmouth

1923-1938 London 1938 to date.

Motto:

Where there's a Willis a way

The Cutty Sark

In the end, clippers lost out to

steamships, which could pass

through the recently-opened Suez Canal and deliver goods more

reliably, if not quite so quickly, which proved to be better for business.

Notably, during the transition period to steam the Cutty Sark sailed faster than

some steamships including mail packets on a destination and condition basis

Cutty Sark was then used on the Australian wool

trade. Under the respected

Captain Richard Woodget, she did very well,

posting Australia-to-Britain times of as little as 67 days. Her best run, 360

nautical miles (666 km) in 24 hours (an

average 15 kn (28 km/h), was said to have been the fastest of any ship of her

size.

Although ships have improved greatly

in carrying capacity and safety they have improved surprisingly little in speed.

The ancient galleys sped along at 6 knots, the caravels of Christopher Columbus

in good winds at 7 knots and few modern ships ever exceed 25 knots. The reason

is that ships face large resistance factor due to moving through water, whereas

the wheel on land benefits from the small value of friction - particularly on

rails, and a plane in the air encounters very little resistance to motion. So it

is natural that much greater advances in speed have been made on land and in the

air. If you smooth out the numbers, there is a factor of ten between the speeds.

Boats 6 knots, car or train 60 knots and a plane 600 knots. There is a well

known definition of sailing as the slowest, most uncomfortable, most expensive

way to get from A to B. Funnily enough the way we have chosen to go round the

world.

The

Clippers

The clipper as it's name implies, is

a fast moving ship, in fact, the fastest type of commercial sailing ship ever

constructed. Developed in the US between 1830 and 1860, clippers became the

preferred ships for bringing immigrants to America, carrying fortune hunters to

California and Australia during the gold rushes and supporting the strong

commercial expansion of the US during that period. Clippers were designed for

speed rather than carrying capacity. Normally three-masted with square sails,

averaging 200 feet in length and very streamlined. A long slender bow and very

tall masts with wide yards that allowed them to carry much more sail than other

ships of the day. The captains commanding these vessels were often obsessed with

speed, pushing their ships and crew to the limit.

At a time when merchant ships

spuddled along at 4 or 5 knots with their heavy hulls and round bows which had

hardly changed since the era of the Spanish galleon, the American clippers were

revolutionary. Fantastic long-distance racers, reaching speeds of 20 knots

reducing to less than 100 days trips that had taken nearly a year.

It was a time of record breakers. In

1845, the Rainbow made New York to China - round trip in seven and a half

months. The James Baines crossed the Atlantic from Boston to Liverpool in 12

days and went round the world in 133 days. The Nightingale did Shanghai to

London in 91 days. The Sea Witch did Canton to New York in 81 days and the

Challenge did Hong Kong to San Francisco in 33 days. In 1854, the Lightening

established the world record for distance covered in 24 hours at 436 nautical

miles, a distance only broken long after the advent of motor-powered ships. We

by comparison are happy at anything over a 100 nautical miles a day with an

average of around 120.

Why was the clipper born in the US

when the great naval power was England? The answer is found in the shipyards of

Baltimore on the Chesapeake Bay, which , since the late 18th century had been

turning out small, swift ships, firstly for the coastal trade, then for the

Caribbean Pirates, the American privateers during the war of 1812 against

England and finally, for the slave trade. Slave-ships had to be swift in order

to keep down the death toll affecting their wretched cargo and to escape the

English warships that pursued them after England and most of the major powers

banned slavery from 1811.

The clippers remained an Anglo-Saxon

speciality, first the US, then the UK and Canada. Not many were built elsewhere,

just a few in France, Germany, Denmark and Holland. America stopped building

clippers after 1860 due to a drop in demand. Great Britain carried on producing

them for the tea trade until 1870, but the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and

the arrival of the motor-powered ship marked the end.

The Taeping had set

off from China with a cargo of tea on the 30th of May 1866 and arrived at

London Docks on the 6th of September at 9.45pm. The 'Ariel' had departed on

the same day and arrived at the East India Dock on the 6th September at 10.15pm.

The first ship home with the new tea crop would be able to command a far higher

price for her cargo, so these beautiful ships, with their large area of sail and

sleek lines, were built for speed. Tea represented one of the main consumer

goods brought to Britain from the East.

Taeping and

Ariel

Speed records on

water.

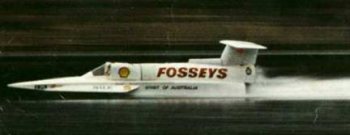

The absolute speed record is the

Spirit of Australia, driven by Ken

Warby (born on the 9th of May 1939) who is an Australian motor

boatracer, he currently holds the water speed

record of 317.60 miles per

hour. This was set in Blowering Dam, part of the Snowy Mountains hydro-electric

scheme, near Tumut, New South

Wales, on the 8th of October 1978. "Spirit" was powered by

a 6000 horse power Westinghouse jet engine. As a child, Warby's

hero was Donald Campbell, who died attempting to break the record in

1967.

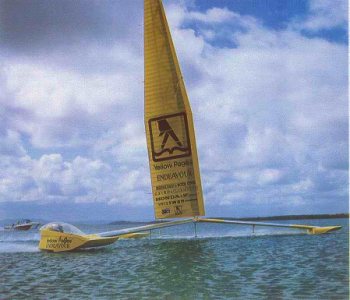

The record for a sailboat is 46 knots

over a distance of 500 metres, held by three Australians on Yellow Pages

Endeavour, a vessel with three planing hulls. There was barely 20 knots of wind

on the day of the record which was in 1993. The boat requires 15 knots plus to

take off, but once planing can go almost three times the wind

speed.

Ken Warby, Spirit of

Australia and Yellow Pages Endeavour

Charlie Barr:

( 1864 - 1911 ) was an excellent skipper, born in Gourock,

Scotland, he first apprenticed as a grocer before working as a commercial

fisherman. In 1884, he took a job with his older brother John, delivering a

sailing yacht, Clara, to America. Clara's racing success was such that in 1887,

John was selected to skipper the British challenger, a yacht called

Thistle, the representative of the Royal Clyde Yacht Club;

Charlie served as a member of the crew. Thistle was soundly defeated by yacht

Volunteer. In the process, however, the brothers Barr were

introduced to Nathaneal Herreshoff, and Charlie Barr's yachting

career was launched, he would sail Herreshoff-designs for much of the rest of

his professional sailing life.

The

America was a 19th century racing yacht which gave its name to the

international sailing trophy it was the first to win the America's

Cup, known then as the Royal Yacht

Squadron's "One Hundred Guinea Cup". The

schooner was designed by George Steers for

Commodore John Cox Stevens and a syndicate from the New York

Yacht Club. On the 22nd of August 1851, the

America won by eight minutes over the Royal Yacht Squadron's 53 mile

regatta around the Isle of Wight.

The

America

America's Cup

success: Captain Charles Barr was skipper of

the yacht Columbia in 1899 and defeated Sir Thomas Lipton's

Shamrock. Two years later, in 1901, Charlie Barr was again at

the helm against a Lipton sponsored racing machine, Shamrock II, a 137 foot

Watson-designed cutter. In 1903, Barr was the captain of the winning yacht

Reliance, one of the most famous racing yachts to be designed by

Nathanael Herreshoff. Barr was inducted into the America's Cup Hall of Fame

1993.

Atlantic at the start of the

race

Atlantic record: Charlie Barr is best

known for setting the record for the fastest crossing by a sailing yacht of the

Atlantic Ocean on the schooner named the

Atlantic in the legendary 1905 Kaiser's Cup Transatlantic Race,

crossing from Sandy Hook Light Ship, near New York to Point Lizard,

Cornwall, a distance of 2925 nautical miles. Barr made his crossing in 12 days,

4 hours, 1 minute and 19 seconds, a racing record that stood for 100 years

for the type of craft, 75 years for any class. Charlie benefitted from an

exceptional series of strong depressions on his crossing. On the other hand,

conditions were rough. When one of the storms was at its worst, the terrified

owner appeared on deck and called for the sails to be reduced. Barr answered

with "You hired me, sir, to win this race, and by God, that's what I am going to

do," and promptly sent the man back to his cabin.

The first to beat Barr's

record was Eric Tabarly in 1980 on the hydrofoil trimaran Paul Richard,

shortening Barr's time by 2 days, and new records have been set frequently since

then. The current record for a crossing by a single-hulled boat has been held by

Bernard Stamm on the Open 60 Armor Lux with a time of 8 days 1 hour, and for

catamarans since 2001 by Playstation with the incredible time of under 5

days.

The record for a distance covered in

24 hours is 695 nautical miles, established in 2002 by the English catamaran

Maiden 2.

St Malo, France -- Maxi catamaran

Maiden 2 has taken the English Channel record by cutting 57 minutes off the 1991

record. Maiden 2 took 5 hours and 24 minutes to

cross from Cowes, Isle of Wight to St Malo, France, finishing at 14:44:04 on

Tuesday. The previous record was set by American

adventurer Steve Fossett in his 38 metre (125 foot) catamaran PlayStation in

December 1991. The Maiden 2 team had an unofficial average speed of 25.7 knots.

Skipper Brian Thompson and crew member Helena

Darvelid were aboard PlayStation for the 1991 record, so both broke their own

record. "We're smoking! I can see St Malo and

were doing 26 knots of boat speed. The wind has held all the way contrary to

what was expected, we've had 15-16 knots the whole time," Thompson said during

the crossing. This latest record is Maiden 2's

fourth record in the last four months. It now holds the Antigua-Newport record;

the 24-hour speed record; the Round Britain and Ireland record and the Channel

record. Project director Tracy Edwards remained

ashore to find a sponsor for a Jules Verne non-stop round-the-world record in

early 2003. Edwards purchased Maiden 2 in March.

The boat was formerly called Club Med and sailed by veteran New Zealand sailor

Grant Dalton in The Race 2000, which it won in a 62-day non-stop

circumnavigation from Barcelona back to Marseille. 2002. British catamaran Maiden II has smashed the round Britain and

Ireland record, completing the course in four days, 17 hours and three minutes.

Britain's Brian Thompson skippered the catamaran

past the previous record, set by American Steve Fossett, in emphatic fashion.

Fossett's Lakota established the record of five

days, 21 hours and five minutes in 1994, but that time now lags over 28 hours

behind Thompson's record run. "We are very, very

pleased to have done the course and feel we did a good job," said

Thompson.

Antoine Albeau is a

French windsurfer who holds eleven Windsurfing World Championships in different

disciplines since 1994. Born on the 17th of June 1972 in La Rochelle,

France, Albeau set a new all-category world windpowered sailing speed

record on the 5th of

March 2008 with 49.09

knots (90.91 Km/h or 56.49 mph) on a 500 metre course at Saintes Marie de la

Mer, beating the

previous record which had been set by Finian Maynard with a speed of 48.70 knots in April 2005 at

the same spot. In October 2008 Antoine Albeau

successfully completed a cross channel windsurf from Cherbourg, France to Sandbanks, Poole. A crossing

of 75 nautical miles (138 kilometres) taking just over 6

hours.

Maiden 2

and Antoine Albeau

ALL IN ALL we

will stick to our record of six seconds doing 10.1

knots.

|