Slavery

You cannot possibly be in the Caribbean learning about the

history, tradition, flora and fauna without the words - sugar - plantation -

slavery.

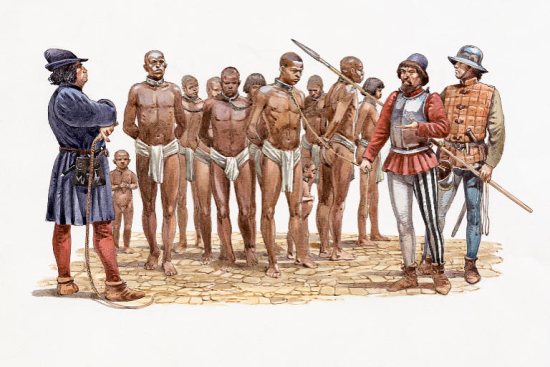

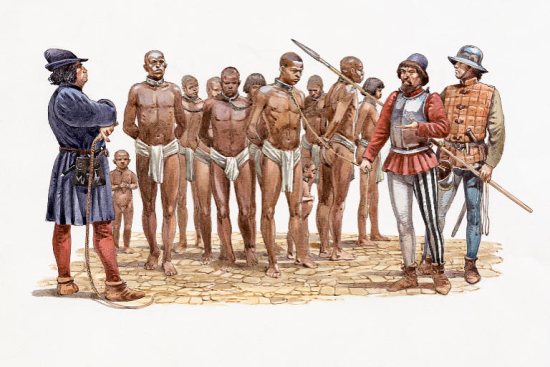

Early mention of the slave trade in Europe:

The government in Spain ordered its agents in Seville to send out 250 slaves for

the gold-mines of Hispaniola; and from 1518, in order to forestall Portuguese

smuggling, the crown began to grant licenses to private traders for the import

of slaves into the West Indies. In this way the third racial element was added

to the West Indian mixture. By the late 1520's all the disciplinary problems of

plantation slavery had made their appearance: shortage of European supervisors -

partly due to the exodus to Mexico; servile mutinies; bands of runaways hiding

in the mountains and emerging at intervals to attack the settlements. Even so,

the planters constantly clamoured for more slaves. There were never enough.

Import was by individual license, though sometimes a monopoly for a period

of years might be granted, with the right to sell individual licenses to

sub-contractors. The licensees had to buy their slaves from Portuguese dealers;

the supply was haphazard and irregular; and the island buyers had to compete

with larger producers of sugar on the mainland.

At first settlers in America imported cane sugar from the West

Indies, however, after the US purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in

1803, plantation owners began growing sugar cane. The crop was labour intensive

and large numbers of slaves were purchased to do the work. The crushed

cane was used for fuel, molasses and as a base for rum. The industry grew

rapidly and by 1830 New Orleans had the largest sugar refinery in the world with

an annual capacity of 6,000 tons.

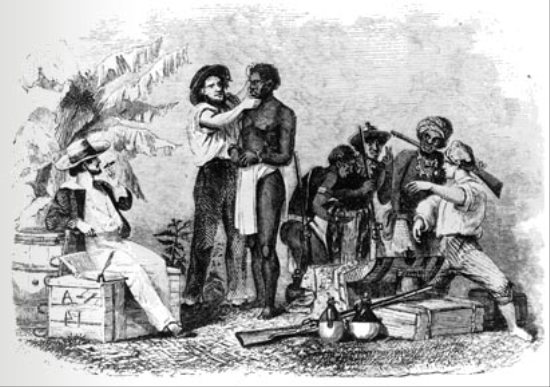

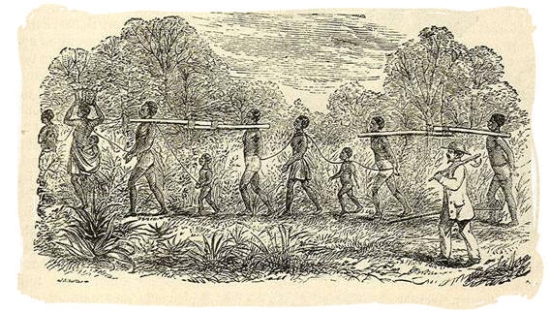

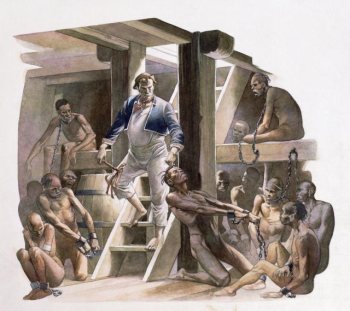

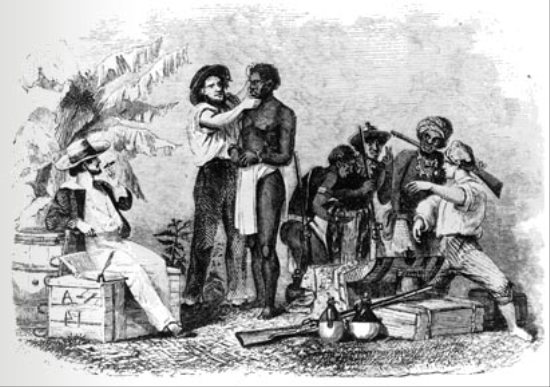

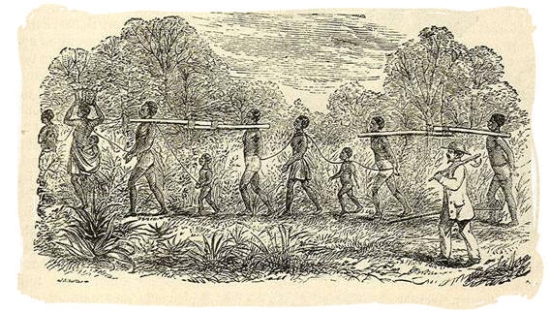

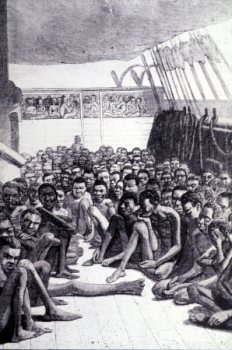

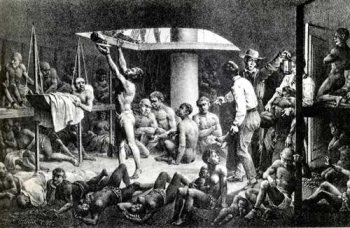

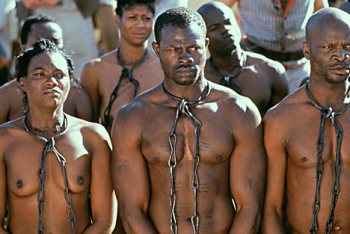

Human cargo: The triangular voyage was usually

at least twelve months. A ship would sail from its home port in England or

France with a cargo of 'trade goods' - woolen or cotton cloth, firearms, other

weapons, tools, pots, pans and trinkets. When the ship arrived off the

African Coast, negotiations begun, usually through resident middle-men, most of

whom were Portuguese half-castes, for slaving the ship. Slaves might be picked

up in small lots here and there; or more commonly assembled in bulk, or in

barracoons ashore. All this trading might take several weeks. Meanwhile, 'trade

goods' were landed in payment, water barricoes filled ashore and temporary decks

constructed by the ships carpenters. On these extra decks the slaves were to

travel, lying prone all night and most of the day as there was no room to sit

upright let alone stand. As soon as the cargo was assembled the slaves were

hurried on board, the ship set sail without delay, carronades trained inboard

and gunners mates standing by with lighted matches until the Coast was out of

sight. Ships’ captains mixed slaves from different nations, creating a language

barrier that prevented the captives from plotting to take over the ship.

Captives usually outnumbered sailors by ten to one on these ships, who suffered

on the voyages almost as much as the slaves and few highly skilled seamen would

join such a ship. Women and children were held in separate quarters and

were at risk of being attacked or abused by the sailors during the

voyage. Once at sea the danger of mutiny was less so some deck exercise was

permitted, though always under strict guard. Ships arrived in the islands after

this middle passage in which speed was of the essence as this was the best

safeguard against mortality, the process was reversed; the slaves might be sold

on board if demand for them was urgent, but usually they were landed,

'refreshed' for a short period ashore on fresh provisions, doctored in

various ways to improve their health and appearance, and then sold at auction,

in small lots, by the agent of the slaving firm, to factor's or local

planters. Planters were bad payers and many of the transactions involved credit.

Unless there was a great shortage of slaves, the planter usually had the

advantage in these trades. The process of sale or

barter might take many weeks. For the ships company this was a time of rest and

release from strain, for once a slave was sold his new owner was responsible for

him. Ship's discipline relaxed; many seamen deserted in the West

Indies, others had to be signed on, usually at rates of pay far higher than

those ruling in Europe - a frequent cause of dispute. Some worn out ships also

remained in the islands, being judged unequal to the homeward passage. The

French but not usually the English, enforced a system to determine seaworthiness

at this stage. Eventually, sales made, crew rounded up and formalities done, the

ships people dismantled the added slave decks and loaded in the return cargo,

usually sugar, for the last leg of the triangle, usually the quickest back to

Europe.

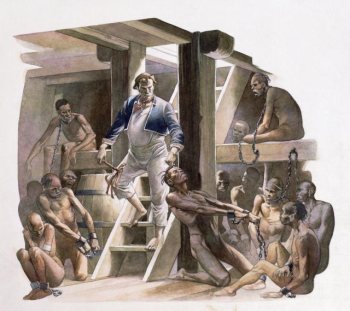

The crew had to load enough water for every person on board, at

least several hundred barricoes. If the cooper was incompetent everybody may die

mid-Atlantic. The carpenter, similarly, was responsible not only for ordinary

structural repairs but for the maintenance of several hundred leg-irons,

neck-rings and pairs of manacles; woe betide officers and crew if slaves

shackles broke while the ship lay off on The Coast. Even the cook had an unusual

task, in having to cater for several hundred slaves in addition to the ship's

company. The senior officers, the captain in particular - needed a high

degree of professional competence, be excellent seamen, had to be

specialised merchants, warders, diplomats and on occasion fighting men. They

were well paid by comparison to most other trades, both in salary and with

opportunities for private trade. They were not necessarily, or usually brutal

sadists of abolitionist propaganda; they did not suffer social stigma by reason

of their trade in the eighteenth century - certainly they were not regarded as

monsters. On the contrary, like merchant officers in other trades, they took a

normal pride in delivering their special type of cargo in as good a

condition as possible. The standing orders of most slaving firms forbade

officers and seamen to strike or ill treat slaves. It took only a few

slaving trips, however to rob a man of any sense of the humanity of the slaves

he carried; for him they became so many cattle, to be treated with no more

or no less consideration than other animals of commercial value. In 1811 on Tortola in the British

Virgin Islands, Arthur William

Hodge, a wealthy plantation owner and Council

member, became the first and only person to be hanged for the

murder of a slave.

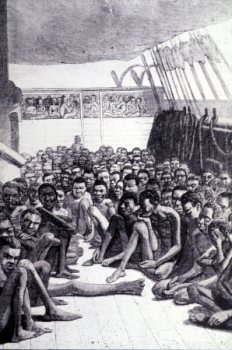

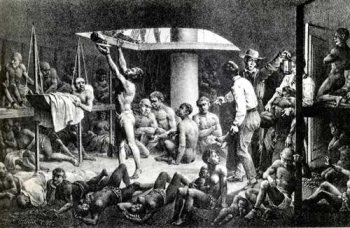

Death at sea: The European crews made sure that slaves were

fed and exercised regularly. Slave ships carried various tools and instruments

to force captives to eat including small hammers and chisels to remove teeth to

overcome hunger strikes. Captives were exercised by being forced to dance and

jump on the deck, sailors would take this opportunity to wash their

prisoners with cold sea water, this they thought helped maintain good

health. However, when disease spread and began kill captives the crews

would throw dead and dying overboard to protect the rest of their

valuable cargo. When ships took longer than expected to sail across the Atlantic

and food and water supplies ran low, many captives were thrown overboard to

ensure that there would be enough supplies for the European crew. Employment in slavers was not only exacting; it was obviously

unpleasant, often dangerous and nerve-racking. Apart from the ever-present

danger of insurrection, ships lay off-shore for weeks on end in hot and

unhealthy estuaries. An outbreak of an infectious disease in the packed

conditions during the middle passage would kill off the greater part of the

company and cargo, hence the insistent regulations about scrubbing decks and

sprinkling with vinegar etc. Even the regular rate of mortality among the crews

of slavers was very high, 20 to 25% on average, and this in an age when health

at sea in general was improving and the incidence of diseases such as scurvy was

being rapidly reduced. It is significant that the death rate among the crews was

usually about the same as amongst the slaves themselves.

Jackson out of Liverpool, extra decks added to carry slaves and The Fluyt of the Netherlands.

A profitable trade: Two out of every five slave ships

sailed to and from ports in the North and South America, and the Caribbean.

Filthy slave ship holds were not suitable for carrying most goods back to

Europe. Instead, other ships transported sugar, tobacco, rice, timber and other

colonial produce back to Europe for sale or to be processed into manufactured

goods. For nearly 100 years sugar remained Britain’s largest and most valuable

import from the slave colonies, only overtaken by cotton in the 1820's. Glasgow

and Greenock on the River Clyde benefited from the triangular trade as their

ships could sail to and from many North American ports on this third leg of the

trade quicker than ships from Liverpool, Bristol or London. Merchants who

participated in the triangular trade became powerful citizens in Britain’s major

sea ports.

Wealth from slave trade: Nearly thirty of Liverpool’s

mayors between 1700 and 1820 were slave merchants, also many MPs and members of

the House of Lords grew rich from the trade and retired to large houses in

Britain to enjoy their fortunes. Thousands of ordinary Britons relied on

the slave trade for their employment at sea or on shore. Ships had to be built,

fitted out and repaired. Dock workers, blacksmiths, carpenters, sail-makers and

rope-makers worked all year round on Britain’s slave trade fleet. Many Britons

found jobs in banking and insurance supplying services to slave merchants. The

wealth and prosperity of many communities depended on the slave trade.

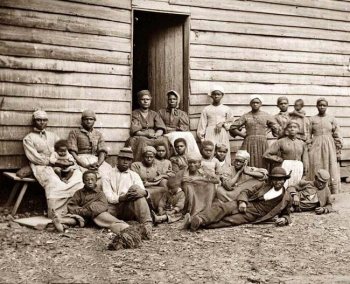

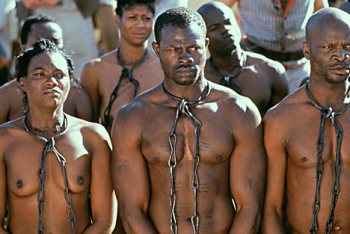

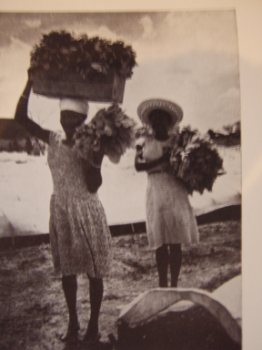

Slaves raking over the coffee beans to dry

in the sun, carrying tobacco leaves and working in the fields.

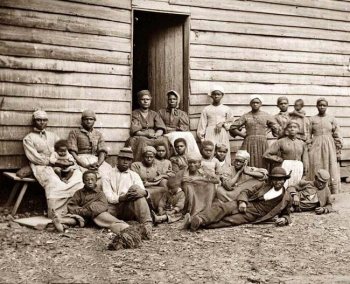

Just some of the children taken,

workers in the southern US taking a break, many

movies have been made showing the plight of

slaves.

Fine of £100 per slave; The transatlantic slave trade ended

and the campaign, supported by tens of thousands of Britons was victorious. The

Abolition of the Slave Trade Act banned British ships from taking part in

the trade. Any slave ship captain was liable to a fine of £100 per captive

and his ship could be confiscated. Ship owners, officers, ship’s surgeons and

anyone else participating in the slave trade could also be fined. Insuring slave

ships was banned and companies were fined £100 for any policy issued. Enemy

ships caught with captives aboard became the property of the British

government.

Britannia rules the waves: Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar in

1805 destroyed the French and Spanish fleets and made Britain safe from foreign

invasion. Control of the seas meant that Royal Navy ships could stop and search

any ship at sea, hoping to outlaw the trade in African slaves. Huge profits

still attracted slave traders and sea captains to risk fines but British law for

the first time made their activities illegal. At the same time, the sugar

plantations on the captured French and Spanish islands were not able to obtain

fresh supplies of captives to compete with the British colonies. The boom was

slowing.

Slavery in the British and French Caribbean: The islands of

Barbados, Antigua, Martinique and Guadeloupe in The Lesser Antilles were the first important slave societies of the

Caribbean, switching to slavery by the

end of the 17th century as their economies converted from

tobacco to sugar production. By the middle of the 18th century, British

Jamaica and French

Saint-Domingue had become the largest and most

brutal slave societies of the region, rivaling Brazil as a destination for enslaved Africans. The death rates

for black slaves in these islands was higher than birth

rates, caused by overwork and malnutrition, slaves

worked from sun up to sun down in harsh conditions, supervised under demanding

masters. Slaves had poor living conditions, little medical care and consequently

they contracted many diseases.

The lodging, clothing and feeding of these armies of

slaves was one of the major problems of the West Indian economy. Slaves usually

built their own huts of timber, thatch and wattle-and-daub, mostly grown on the

estate. More substantial buildings would have to be roofed with imported

shingles, which was expensive. They wore clothes supplied by their owners - two

suits per year was the usual allowance in both the French and British islands -

and various types of coarse linen cloth - osnaburg, Dutch Stripes and Guinea

Blue - were manufactured expressly for this market in England and France. As for

food, the proprietor of a plantation could import it, grow it on part of

his land, or allow land and time to his slaves to grow it for themselves. In

Saint-Domingue and Jamaica, which were the chief sugar planting areas in the

eighteenth century, it was the custom to set aside marginal land, usually in the

foothills, as provision grounds.

For centuries the slave trade made sugarcane production

possible, the low level of technology made it a difficult and labour

intensive product. At the same time, the demand for sugar was rising,

particularly in Great Britain. The French colony of Saint-Domingue quickly began

to out-produce all of the British islands' sugar combined. Though sugar was

driven by slavery, rising costs for the British made it easier for the British

abolitionists to be heard.

With abolition the new British colony of

Trinidad was left with a severe shortage of labour,

this shortage became worse after the abolition

of 1833. To deal with this problem, Trinidad imported

indentured servants from the 1830's until 1917.

Initially Chinese, free West

Africans and Portuguese from the island of Madeira, but they were soon supplanted by

Indians. In addition, numerous former slaves

migrated from the Lesser Antilles to Trinidad to work.

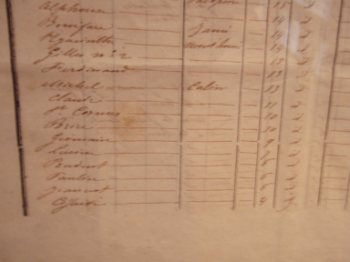

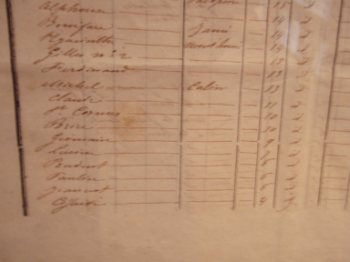

An inventory of taken slaves on the left the

oldest is 68 on the right the youngest is 4 years old. The central

photograph famously shows Peter Baton's back covered

in scars from his beatings.

Whitehall in England announced in 1833 that slaves

would be totally freed by 1840. In the meantime, the government told slaves they

had to remain on their plantations and would have the status of

"apprentices" for the next six years. On the 1st of August 1834, an

unarmed group of mainly elderly Negroes being addressed by the Governor at

Government House about the new laws, began chanting: "Pas de six ans. Point de

six ans" ("Not six years. No six years"), drowning out the voice of the

Governor. Peaceful protests continued until a resolution to abolish

apprenticeship was passed and de facto

freedom was achieved. Full emancipation for all was legally granted ahead of schedule on the

1st of August 1838, making Trinidad the first British colony to

completely abolish slavery. After Great Britain abolished slavery, it began to

pressure other nations to do the same. France, too, abolished slavery. By then

Saint-Domingue had already won its independence and formed the independent

Republic of Haiti. French islands were limited to

the Lesser Antilles.

Slavery and negotiating freedom: Between 1662 and 1807

Britain shipped 3.1 million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean in the

Transatlantic Slave Trade . Africans were

forcibly brought to British owned colonies in the Caribbean and sold as slaves

to work on plantations. Those engaged in

the trade were driven by the huge financial gain to be made, both in the

Caribbean and at home in Britain. Enslaved people constantly rebelled against

slavery right up until emancipation in 1834. Most spectacular were the slave revolts during

the 18th and 19th centuries, including: Tacky’s rebellion in 1760’s Jamaica, the

Haitian Revolution (1789), Fedon’s 1790's revolution in Grenada, the 1816

Barbados slave revolt led by Bussa, and the major 1831 slave revolt in Jamaica

led by Sam Sharpe. Also voices of dissent began emerging in Britain,

highlighting the poor conditions of enslaved people. Whilst the

Abolition movement was growing, so was

the opposition by those with financial interests in the Caribbean. The British

slave trade officially ended in 1807, making the buying and selling of slaves

from Africa illegal; however, slavery itself had not ended. In 1811 an Act of

Parliament made slave trading illegal, in 1827 it was declared to be piracy and

punishable by death. Other nations legislated against the trade; Sweden in 1813,

Holland in 1814, France 1818 and Spain in 1820, these latter two powers

were half-hearted about the matter and slave dealing was an open business

in ports like Nantes, which had some eighty slave ships and where the profits

from the trade were said to have amounted to 90,000,000 francs in the year 1815.

The total number of slaves taken from West Africa after the Abolition Act of

1808 may in fact have been greater than those taken before that date; it is

certain that both Cuba and Brazil imported greater numbers after 1808 than they

did during the earlier period, Cuba was importing slaves up to 1865, Brazil even

later. In Cuba and the US the demand for slaves increased after 1808 because of

the greatly expanded production of sugar, cotton and tobacco.

It was not until the 1st of August 1834 that slavery ended

in the British Caribbean following legislation passed the previous year. This

was followed by a period of apprenticeship with freedom coming in 1838. Even after the end of

slavery and apprenticeship the Caribbean was not totally free. Former enslaved

people received no compensation and had limited representation in the

legislatures. Indentured

labour from India and China was introduced after

slavery. This system resulted in much abuse and was not abolished until the

early part of the 20th century. After indenture, Indians and Africans struggled

to own land and create their own communities.

One of the simplest ways to understand the changing sentiment

over time in Europe is to view the changes by year and country:

-

1792. Denmark. A partial ban on the

slave trade is passed and put into effect in 1802.

-

1806. Britain.

Sale of slaves to non-British colonies is banned.

-

1807. Britain.

Import of slaves to British colonies is banned and outlawed the following

year.

-

1807. Denmark. Total ban on all slave

trade.

-

1814. Netherlands Slave trade outlawed.

-

1818. France. Slave

trade outlawed.

-

1820.

Spain. Slave trade formally

outlawed, but illegal trade to Puerto Rico and Cuba tolerated until the 1850’s

and 1860’s.

-

1834. Britain.

Slavery abolished, though apprenticeship period was set to last until 1838.

-

1848. Denmark. Slavery abolished.

-

1848. France. Slavery

abolished. The 23rd of May abolition in Martinique, 27th

May in Guadeloupe. 10th of August in French Guyana, 23rd

of August trading posts in Goree and Saint-Louis in Senegal.

December the 20th Reunion Island.

-

1848. Netherlands. Slavery abolished on Sint Maarten.

-

1848. Netherlands. Slavery abolished on other

colonies.

-

1873. Spain. Puerto Rico's slavery is abolished.

-

1879. Spain. Abolition on Cuba, but unpaid labour required

until 1886.

The abolition of the slave trade in Britain had a strong effect

throughout the Caribbean, as the English were the suppliers of many other

islands' slaves.

Religion and Slavery: The enslaved part of the

population went through an initiation of sorts. Newly arrived slaves had to

be 'seasoned', that is, they had to be given time to adjust themselves

physically to their new environment. They learnt their work under the direction

of a driver or from a Creole slave, the traders were taught by craftsmen

brought out from England. The purpose of training was to get as much value as

possible in labour from the slave, and the same purpose directed the

training of the children through the 'Pinckney gang'. The only people who

thought slaves should be taught to read and write were the missionaries. The

planters regarded literacy as a sort of social dynamite, but in 1760 the

Moravians were allowed to begin the instruction of slaves in the Christian

religion because they taught acceptance of the rule of the master. As the

evangelical movement gained in strength in England the habit of reading the

Bible spread, and out of this there sprung a mass movement in literacy in

England in the early nineteenth century. At the same time in the West Indies the

missionaries pressed forward with their efforts to christianise the slaves. In

1797 the Barbados Consolidated Slave Act made it the duty of every Anglican

rector to set a time every Sunday for instructing the slaves in the doctrines of

Christianity, but it was illegal to teach reading and writing. Real education

did not begin until well after 1838. In Britain particularly, religion became an

important reason not to participate in slavery. However, religious motivations

were not part of the abolition movements in other countries. In France and

Spain, public officials and intellectuals made up the majority of abolitionists.

In these countries and other Roman Catholic nations, the majority of the

religiously affiliated abolitionists were Protestants. In fact, the pope did not

condemn slavery until 1839, and Britain was responsible for the pressure on

other nations to stop using slave labour.

Rising Sugar Costs: One of the most important early

arguments for slavery was that it kept the cost of sugar low. However, the

British islands, particularly Jamaica, were having trouble proving this point.

In fact, the British government headed a number of initiatives to help improve

the quality of life for the colonial slaves, including the amelioration

initiative in 1823. Nothing could stop the price of British sugar from

skyrocketing, and the increase in sugar consumption had made it difficult for

Britain to handle the rise in cost. When it became clear that the rising price

of sugar could not be stopped with slavery, Britain became more forceful with

its most rebellious colony, Jamaica, whose Assembly had resisted all abolition

measures at every turn.

An article that appeared in

Harper's

Abolition in Britain: Rebellions were another drain on

slavery. These increased greatly throughout the British islands after 1815.

While some attribute these revolts to worsening conditions brought on by

abolition, which forced harder work from already overworked slaves, others blame

it on the rapid spread of Protestant Christianity among the slaves. A slave

rebellion led by Baptist preacher Samuel Sharpe began just after Christmas in

1831, and more than 200 sugar estates on Jamaica were burned and pillaged.

Regular troops fought the slaves, and 540 slaves died after the revolt was put

down. This outraged the English, but they were wary of Haiti's rebellion by its

slaves, so England created a period of compulsory work after abolition known as

"apprenticeship." In 1823, the historic Abolition Act was passed, and it ended

slavery in August of the following year. Agricultural workers would be required

to work for their former masters until 1840, but domestic staff would only have

to work until 1838. They would be allowed to buy their own freedom at any time.

The former slaves would be given food, clothing, lodging, medical care and in

return they would give 45 hours per week of unpaid labour. They could also work

on their own, for pay, during their free time, and Britain sent special

magistrates to settle any disputes. However, full abolition came about somewhat

earlier than planned, in 1838. The abolition of slavery in the British colonies

had long-lasting and far-reaching effects. However, the remaining European

nations did not place emancipation of their slaves as a top priority.

William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833) A very important

person in the abolition of slavery: William Wilberforce was a wealthy

young man and at 21 became MP for Hull in the Tory government led by his good

friend William Pitt. Wilberforce heard John Newton preach in London and became a

regular visitor to Newton’s house. Wilberforce listened to Newton’s descriptions

of the horrors of the slave trade. Abolitionists such as Clarkson and Sharp met

Wilberforce and persuaded him to join the Society for the Abolition of the Slave

Trade.

First Bill defeated: In 1789 Wilberforce made his first speech in

Parliament on the subject of ending the slave trade. Two years later Wilberforce

introduced a Bill (or draft law) in Parliament to abolish the slave trade. He

had the support of Pitt, the Prime Minister, he was an eloquent speaker

with a mountain of evidence gathered by Clarkson to support the case against the

evils of the trade in human cargo. However, the slave traders and slave owners

had too many friends and allies in Parliament. Wilberforce’s proposal was

defeated for the first, but not the last, time.

Extract from Wilberforce’s 1789 Abolition speech to Parliament.

This is known as one of the great speeches of history, the full speech lasted

almost 4 hours long: “I must speak of the transit (transport) of the slaves

in the West Indies. This I confess, in my own opinion, is the most wretched part

of the whole subject. So much misery condensed in so little room, is more than

the human imagination had ever before conceived…A trade founded in iniquity, and

carried on as this was, must be abolished, let the policy be what it might, -

let the consequences be what they would, I from this time determined that I

would never rest till I had effected its abolition“.

Long struggle: Every year, Wilberforce introduced a Bill to

abolish the slave trade in the House of Commons. Each year, the majority against

Wilberforce’s proposed new law got smaller until the House of Commons passed the

Bill in 1805. But the Bill was rejected by the House of Lords. It took nearly

twenty years for the number of MPs and Lords willing to end the slave trade to

outnumber those determined to see it continue. In 1807 Wilberforce’s Bill was

passed by both Houses of Parliament. 114 MPs had voted for the Bill and only 15

against. The Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade made the slave trade

illegal throughout the British Empire. The Abolition Act put Britain out of the

slave trade at a time when more than one-half of the trade was in British hands.

It did not put an end to the trade itself, others moved in to take what the

British gave up and their were many English slave smugglers carrying on

supplying slaves. The US government declared the trade illegal in 1808, however,

many Americans continued to engage in the trade, evading the law by selling

their ships nominally to Spain.

No rest until slavery was abolished: Wilberforce, Clarkson,

Sharp and the other leaders of the abolitionist movement did not rest until

slavery was abolished throughout the colonies. The fight to end the trade was

won, but the anti-slavery campaigners knew that African slaves still faced lives

of extreme hardship and injustice. Wilberforce died on the 29th of

July 1833, three days after the Slavery Abolition Bill had been passed by the

House of Commons. He died knowing that at last slavery would be abolished

throughout the British Empire.

ALL IN ALL the fact of taking a person

from their home, family and life was wrong and had to be

abolished.

.

|