Creation, destruction and beauty

|

Sunday 14th February 2016 Today we finished the drive to Strahan, stopping off at a

couple of places along the way. Just a few kilometres along the road from

Bronte Park we came across The Wall in the Wilderness. The wall in

question is made of 3-metre high panels of wood, into which scenes from the

history of Tasmania have been sculpted by artist Greg Duncan. His aim is

to create a 100-metre long wall which will tell the history of the harsh

Central Highlands region and commemorate those who helped shape its past and

present, beginning with the indigenous peoples, then to the pioneering timber

harvesters, pastoralists, miners and Hydro workers. We had no idea what to expect when we paid our $12 each

entrance fee, but the guy in the ticket office assured us it would be worth

every cent. He was absolutely right. From the sculptures in the

entrance lobby – a workman’s jacket carved from wood that looked so

much like cloth that I wanted to reach out and feel its softness – to the

massive work in progress that is the wall, it was fascinating. The detail

in the work was amazing. The sculptor had deliberately left a piece of each

panel unfinished – a horse’s back leg, a man’s arm – so

that one could see stages of his work and how he had transformed a piece of

wood into scenes that were almost alive. Truly impressive. I had to

remember to close my mouth as I stood and marvelled at the artist’s

skills and took in the stories they told.

We had no idea of the treasure hidden inside this

building. Photo

courtesy of Outback spirit tours. No cameras were allowed inside. From here we stopped next at Lake St Clair. This is at

the southern end of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park, the

opposite side of the mountain we visited last weekend. We plan to return

here on our way back to Hobart to do some walking by the lake, so for

today it was a quick stop at the visitor centre to get some walks info and to

take a look at the lake. We wandered around the displays in the visitor

centre before setting off once more for Strahan.

Interesting information about the threatened Tasmanian

Devil. A

newborn attached to a nipple in its mother’s pouch. Tiny.

The critter on the right looks just like Steve’s

unfriendly friend. Glad it was inside a glass case, and more importantly,

dead! We drove on through beautiful mountain scenery, until we

approached Queenstown, where suddenly the surroundings changed. Instead

of forested hillsides in shades of green there were suddenly huge areas of

orange and yellow bare rock. The change was dramatic and rather shocking.

A waterfall finds its way down the hillside. The

dramatic change to bare rock as we approached Queenstown. As we drove along pondering why on earth this landscape was

so different to everywhere else, we came across a laybay with a viewpoint over

the town of Queenstown below, and an enormous information board that explained

it all. Don’t you just love the Aussies’ penchant for

information boards? Who the heck needs Google in this country?!

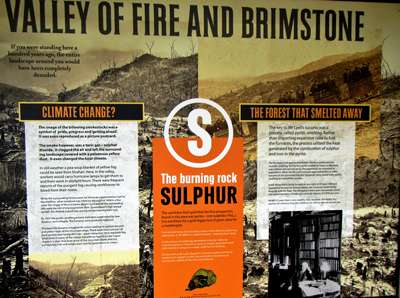

The info board told us why the landscape changed in this

area. It seems that the rocks which make up Mounts Lyell and Owen

and the surrounding area, where we now stood, contained vast quantities of a

variety of metal ores. In the late 1800’s the nearby creeks were

being panned for gold, and during the search an outcrop of oxidised rock was

found, which indicated the presence of mineral ores below the surface. The

‘fool’s gold’ which was found by the first prospectors was

actually pyrites, or iron sulphide. It was useless to the prospectors, but

from ancient times the incendiary nature of sulphur had been well known –

the ‘brimstone’ of the Bible. With the discovery in the area of

not just gold, but silver and copper, tin and iron, fuel was needed for the

smelting plants that extracted the metal from the rock. A long way from

supplies of coal to fuel their furnaces, they turned instead to the pyrites

which was so abundant and readily available. This was to be the kiss of death for the surrounding

hillsides. The smelting plants used the recently developed process of pyritic

smelting, which utilised the heat generated by the combustion of sulphur and

iron in the pyrites. In the closing years of the 19th century,

Queenstown was referred to in the press as “Copperopolis” –

the Copper Town - as its smelters churned out thousands of tons of copper.

The image of the billowing smokestacks was a symbol of pride and progress, but

the smoke was a toxic gas – sulphur dioxide. It clogged the air and

left the surrounding landscape covered with a poisonous yellow dust. It

changed the local climate – workers would carry hurricane lamps during

the daytime to light their way to work through the yellow pea-souper fogs that

could be seen from Strahan, over 30 kilometres away. Some of the surrounding forests were cut down as

supplementary fuel for the smelters, but what remained was killed by the

sulphur. Within a few years the slopes of the mountains were devoid of

all vegetation, and with Queenstown’s high annual rainfall, the shallow

topsoil was quickly washed away, leaving bare rock. By 1921 the pyritic

smelting process had been superseded, but the preceding twenty years of

pollution had changed the surrounding landscape forever. Over the last

100 years, slow re-growth has taken over in the valleys, but with no topsoil on

the higher slopes, it is likely that the bare rock will remain for generations

to come. A fascinating piece of history that demonstrates how, in our

ignorance, we have changed our environment irrevocably. But even as I

felt sadness for the damage wrought to these hills, I couldn’t but

marvel at the colours, textures and shapes of the barren rock which seemed to

have a beauty of its own.

Approaching Queenstown, the first signs of change in the

landscape.

The effects of 20 years of pyritic smelting become

clearer as one descends into the valley and Queenstown itself. |