Seppings Lake

|

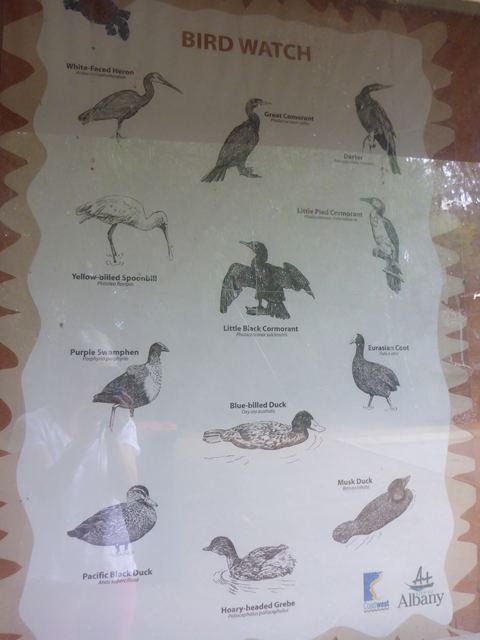

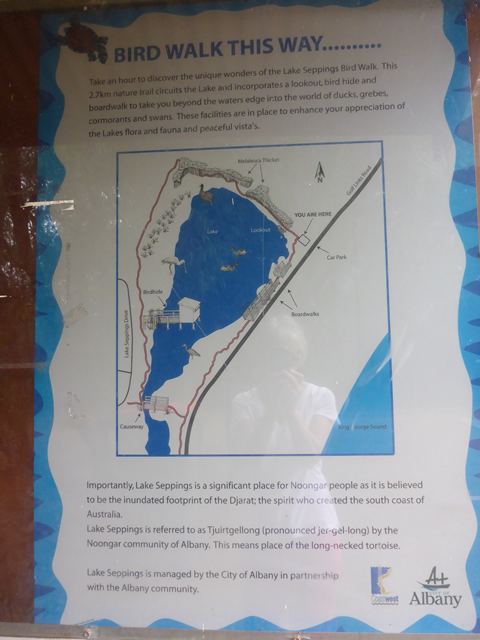

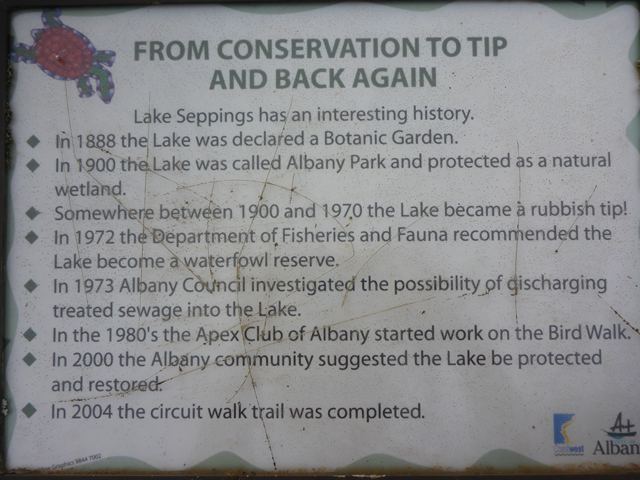

Djarat’s Footprint Where the Long Necked Turtle lives The locals call it Seppings Lake and we first came late one afternoon to walk the loop and see what we could find. Djarat was one of the old spirits known to the local Noongar people. He strode through this soggy part of South West Australia to create the south coast leaving his footprint behind. Clear fresh water filled the footprint known to us recent mortals as Seppings Lake. Quickly the water birds and small animals moved in including the long necked turtle, which we didn’t see but two other beautiful creatures we did spot without any searching required. The King Skink Lizards were basking in the warm sun on exposed rocks and logs and had the helpful habit of staying put just long enough for me to photograph them before they skittered away. Handsome little creatures they are, harmless and shiny armoured. The lake itself is suffering from lack of water and the upper little lake which tends to stay reasonably full is feeding the lower main lake with an intermittent trickle. A victim of the long term drought and that old ally, climate change. It was on our Mount Clarence Circuit walk that I took the photo looking down on the lake and you can see how close it is to Middleton Beach at the head of King George Sound, to the right of the picture and Emu Point to the top of the photo, where the beach ends. Remarkable then that the lake used to be the source of the freshest fresh water, untainted by the nearby ocean and relished by man and Emu alike and I suspect that is why Zoonie’s home is called Emu Point, not because of the shape of any shoreline in the area. Of course it has been a rag to riches and back again story since Europeans arrived. Settlers valued the freshwater supply from the start, then some had elevated idea to turn it into a botanical garden. Through mysterious circumstances, perhaps political will or ignorant neglect it became the local tip and thanks to more enlightened minds and the power of the community it is now a slowly drying haven for wildlife and humans alike. Thank goodness there are no social distancing rules on the range of the human voice; we chatted to lots of people and their dogs as we took our two separate walks around the lake. Coming from the causeway across the stream that links the lakes we started out on a clay gravel path and saw a black snake wriggle hastily from one side to the other and climb over a pile of dry grass into the thick green undergrowth, but not before I got the picture you see. “Ah that’s a tiger snake, there are hundreds around,” the lady in red said, “When people phone the parks office to ask for the snake in their bath/garage/boot or whatever to be removed they release them down here.” Ours didn’t have the striking yellow belly like the one we saw a few days later, when I was on a camera break, which I always regret because there is a worthy photo every time. “They won’t hurt you as they are shy, just stay on the path and you’ll be fine.” They are one of the 50 or so venomous Australian snakes who will strike in self-defence, just like an old lady with a stick. The rest of our enchanted circuit was filled with calling frogs, tiny yellow bellied birds pecking away at the cracked mud of the lake bed, colourful parrots in the trees, pelicans gracing the waters, a white faced heron fishing and occasional joggers and dog walkers. Work to clear these precious waters of the harmful fertiliser run off from local gardens is on-going. Man helping nature in her struggle to survive.

|