Aus Fraser Island

|

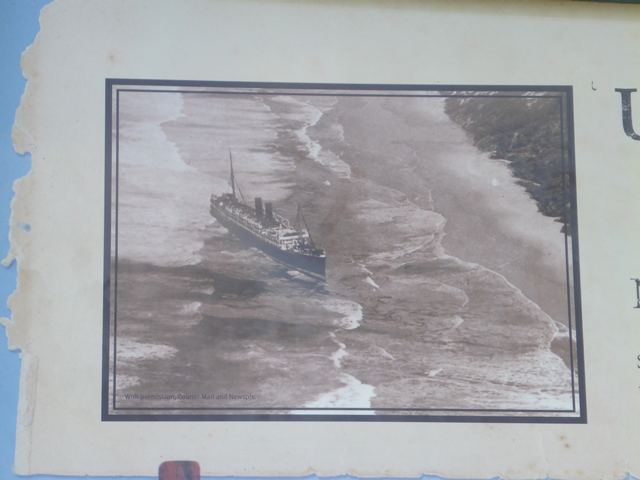

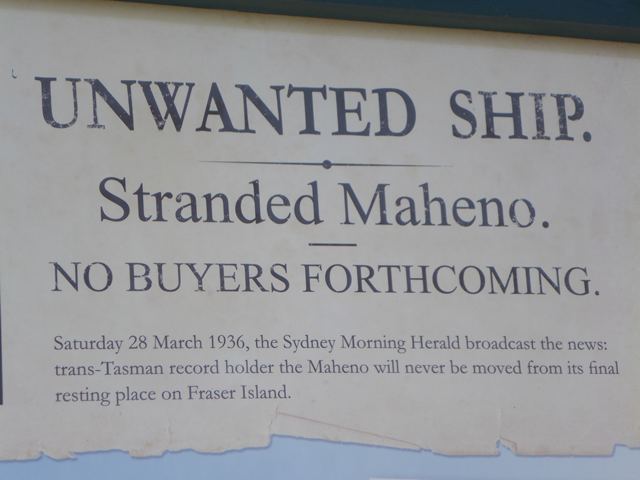

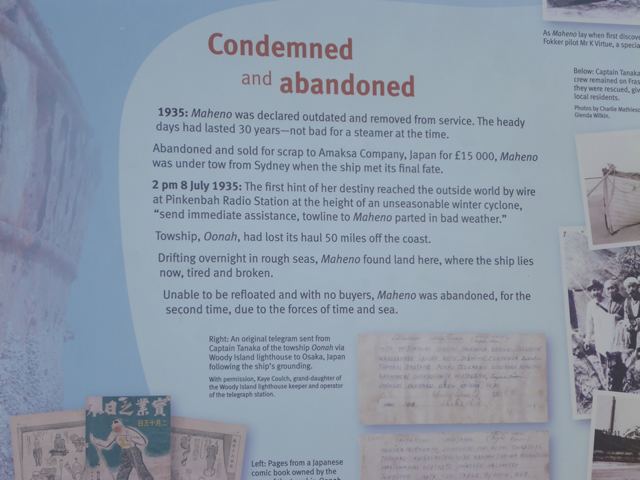

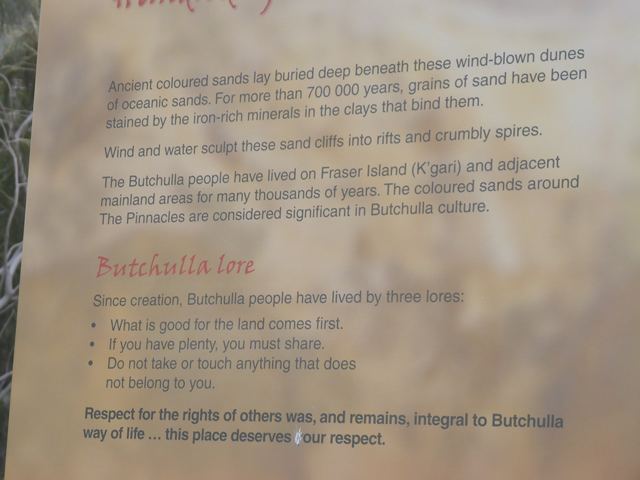

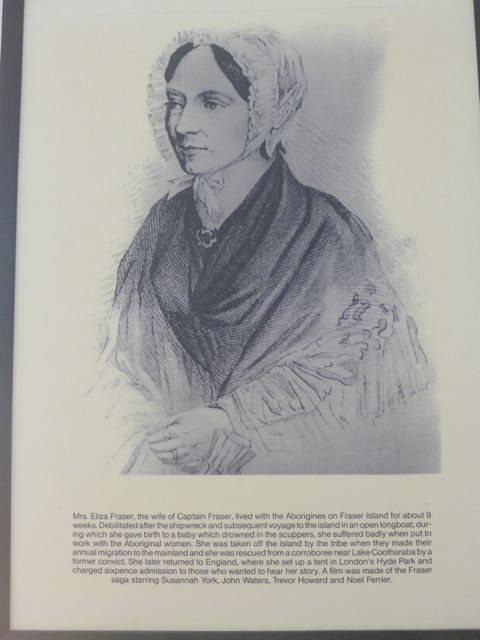

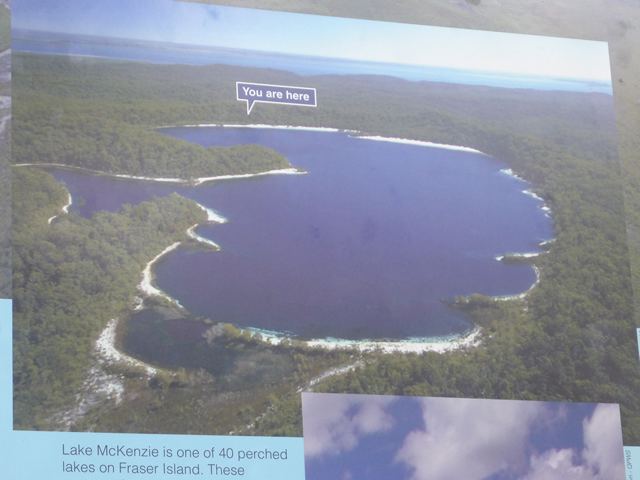

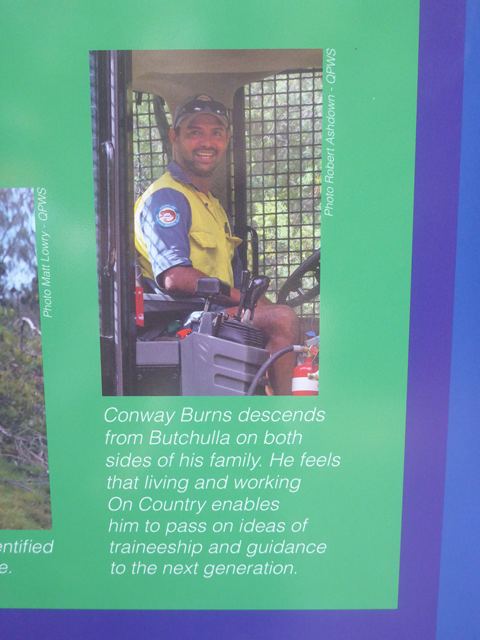

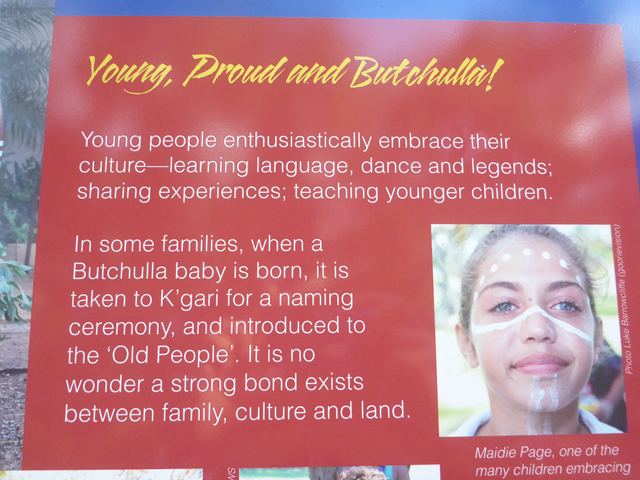

Fraser Island named after Eliza Fraser but soon to be renamed K’gari (Paradise) By the Butchulla People 25:23.15S 152:58.003E In 1836 the Stirling Castle brig was under sail and bound from Singapore to Sydney with 18 crew and passengers on board and under the command of Captain James Fraser when she hit a reef in the Great Barrier Reef and was irreparably holed. The crew along with Eliza Fraser, the Captains pregnant wife in imminent likelihood of bearing her fourth child, took to the ship’s lifeboat and pinnace. The crew in the leading boat towed the Captain and his wife and their small group towards Brisbane but since their boat was taking in water the crew cast it off to beach on K’gari, possibly for their own best chance of survival. They landed at Waddy Point just north of Cook’s Indian Head and started making their way south towards Hook Point, surviving on pandanus grass and berries. At some stage they were taken in by local aborigines. Captain James made himself unpopular by refusing to work alongside the natives and died in mysterious circumstances either by starvation or from ‘injuries’ or both, either way one crew member said it was ‘natural causes’. Eliza, who had given birth while in the small boat where the infant drowned in the scuppers, decided it was better to work with the ladies of the tribe and stayed with them for six weeks. Then either the tribe took her group to the mainland with them for their annual Jamboree where she was ‘rescued’ by a convict and taken to Sydney, or she was rescued on the island by a convict and taken across the water to Double Island Bay and on to Sydney. It was Lieutenant Robert Dayman in 1847 who was the first European to sail between K’gari and the mainland so Eliza may well not have known she was on an island unless the natives told her so. Eliza Fraser; Infamous Opportunist or Innocent Victim of Circumstance? You decide. In Sydney Eliza set up a charity to raise money for her three children back home and then secretly married another sea captain, Alexander Greene, six months after James’ demise and together they returned to England, the £400 charity haul tucked safely inside her bodice. She appealed to the Lord Mayor of London to be allowed to set up another charity for her ‘penniless’ children and their widow mother. This conniving lady then embarked on talking tours of the UK and eventually Australia, telling various ‘stories’ about her capture and ill treatment at the hands of the ‘cannibalistic savages’ in order to raise money. She soon twigged that the more outlandish her stories the more money she made, the effect of which was fatal for many of the aborigines living on K’gari. When colonists and settlers migrated to the area they would take hunting trips, often on religious holidays like Christmas and Easter to kill as many natives as they could based on their Eliza Fraser induced fears. It is, then, hardly surprising that she is now part of Australian folklore, alongside Ned Kelly, and has been immortalised in various forms including through the art of Sidney Nolan, some of whose work Rob and I saw in the Art Gallery at Adelaide. It could be said she got her comeuppance under the wheels of a carriage in Melbourne in 1858. Some 88 years before Cook had made his way up the coast as I have said before, so I was perplexed when our tour guide, Peter said that Cook made three mistakes about the island. One, he thought it was part of the mainland, two, he said there was no fresh water there and three, there were no trees worthy of harvesting. Cook never investigated whether there was a way through between the lagoon he saw to the south and the lagoon he correctly assumed was there in the north. Peter then said it was Matthew Flinders aboard his ship the Investigator who confirmed it was an island. Incorrect. A crew from the Investigator voyage companion ship, the Lady Nelson, went in to the lagoon at the north but Matthew did not confirm whether they managed to get right through the waterway. It is unlikely they would have been away from their mother ship long enough to cover the 36 miles south and the same back to the Lady Nelson. Seventy two miles under oars! Cook saw many natives so he would have known there was fresh water there, Matthew Flinders made exactly this deduction in his book published in 1814 after his 1799 and 1802 visits. Finally, regarding the trees Cook merely stated the trees near the shores were low and bushy, he was more used to the mighty kauris of New Zealand standing on the shores to greet them in those previously visited waters. One thing Cook did note, the intelligence of which confirms his possible thoughts about water, was that the ‘sand blows’ were moving acres of sand through which he could see live and dead trees protruding. Obviously the sand must be on the move to bury and expose trees as the sand blows along. Matthew Flinders could not see why Cook should think the dunes were on the move! Our 4 x 4 blue, high wheel-arched coach bounced and swayed along the deep rutted and very dry sand tracks. We needed to wear seat belts so we could not be shot upwards and bang our heads on the coach roof. Branches screeched along the windows and we rocked from side to side in true trade-wind sea rolling style. Peter explained that there is a freshwater lake underneath the island the volume of which is 7 times that of Sydney Harbour, so all over the island this pure fresh spring water fills lakes and runs downstream to the sea all around the island shores. From 1860 to 1992 the island was stripped of all its useful wood, Australian Kauris, Brush Box Trees, She Oaks, Hoop Pines, Paper Barks (Melaleucas) and Turpentine Trees (Syncarpia, Satinays). The latter with their open bark were so rot-proof they were used in marine projects like the Suez Canal and the rebuilding of Thames Docks after the Second World War. But if they were taller than the canopy they often twisted in the wind and when sawn their grain was found to be cross-grained and so they were not suitable for building. We saw lots of the spared and twisted beauties. We were to think ourselves lucky we had a nice air-conditioned coach with strong windows and excellent uplifting suspension, as Peter said the first tours were done in open-sided army trucks with canvas roofs, where folk sat on wooden seats. Despite our good fortune we were all quite relieved to stretch our legs at the Stonetool Sandblow, so named because of the aboriginal tools found nearby, and as may well have been viewed by our fine navigators from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Seventy Five Mile Beach is an ambitious name because the total length of the island is only about 65 miles and the beach does not extend the full length. I guess it might have felt as long when the Fraser’s were struggling along it! But it was fun driving along it and discovering some of the victims it has claimed in the past and recently. The solitary blue coach broke down the day before and the chap kneeling beside his 4wd is no doubt wishing he had avoided the soft sand. I didn’t see the roof of the car that had gradually been buried in the sand after trying to take a swim, but I was prepared to believe Peter on this one. The most iconic victim of the sands is the once magnificent luxury liner, the Maheno and I will let the photos tell her story except for the fact that she was still pretty much intact before she was used as target practice in preparation for WW2 action. We had a delicious buffet lunch at the McKenzie Resort at Eulong before continuing on to Central Station, once a terminus for the logging trains and now a peaceful wander through the wet sclerophyll forest alongside one of the typical sandy bottomed freshwater streams, the Wanggoolba Creek. Our last stop was Lake McKenzie for a swim in the pristine water. We had to be careful not to wander out beyond where we could see the sandy bottom as the lake shelves steeply to 90 feet in the centre. We didn’t stay in long anyway as the wind was chilly. Back on board Zoonie one of the most inspirational parts of the day was watching two whistling kits buzzing a beautiful White Bellied Sea Eagle above us. The contrast in size and colouring confirmed it was an eagle and the grace with which is soared and swung without moving its wings to avoid the kites was memorable. There are numerous private homes on the island but it is in no way spoiled or overcrowded. In 2014 certain Native Rights were given back to the indigenous Burchilla people to permit hunting, fishing and taking fresh water. These will hopefully be extended so the aborigines can enjoy the benefits of ecotourism. Already much of the running of tours and maintenance of the island is down to members of the Burchilla clan.

|