Flatlands and Blue Penguins

|

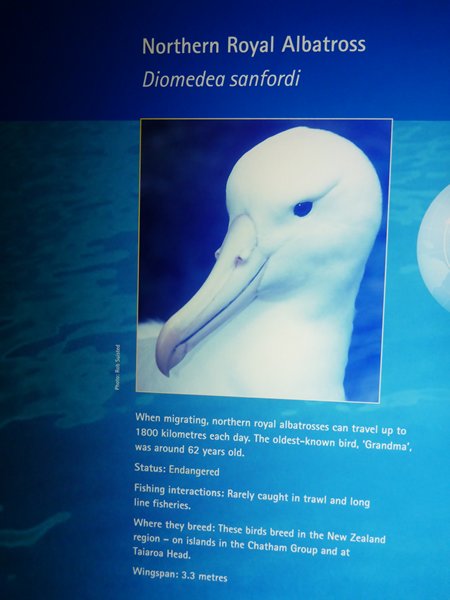

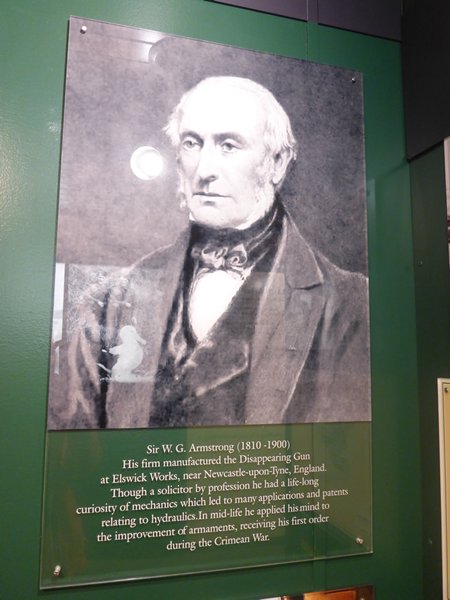

Intense Agriculture on the dry flatlands between Christchurch and Dunedin. Eighty six percent of New Zealand’s drinking water goes on the irrigation of grasslands to feed, mostly, the vast dairy herds in what would otherwise be the semi-desert of the east coast of S Island. It seems a shame they have the climate for all year round grazing, but not the rainfall, in this marginal region. The cost of producing the milk must be astronomic and much of it goes to the lucrative export market after passing through the giant dairies who cream much of the profit, I just wonder how the farmers are faring. It is always a struggle in a primary industry like agriculture since the farmers cannot question what they pay for feed and water and are told what they will be paid for their milk. Between the devil and the deep blue sea, in this case the lovely passive South Pacific. The towns were a little light relief from the flat fields to the horizon. Some farmers around here came from Devon, I thought as we sped through Ashburton, cheerful bright red tractors lined up precisely infront of the Massey Ferguson dealership. In one place there was a novel Motel where you could stay in a silver silo, complete with windows and your own balcony. The mighty wide Rakaia River was down to a trickle, clearly this Eastern Southlands Region was suffering a drought; so different to what the weather had in store for the North Island. Big bales in the fields reflected the big business of farming. NZ magpies in their white cloaks strutted about on the road like barristers summing up in court and acres of lavender, sheep and shiny cows spread to the far horizon. A Clydesdale Horse Stud surprised us, we wondered what they used them for. Pastimes here are all outdoor, from bowls in the towns to golf, trotting clubs (one or two horses infront of a very light carriage, a kind of dressage with wheels) and vintage cars in the countryside. The temperature was rising the further south we went until we approached Timaru on the coast where a cool sea fret reduced it to 21’. Folk were relaxing on the tiny beach in the harbour and we bought ice creams from a café built of rusted steel plates. Very rustic. Back on the road we were approaching the Otago Region behind a chip lorry which sported the slogan “In starch we trust”, I quite liked that. We headed for the Otago Peninsular which runs parallel with the coast enclosing Otago Harbour and was first settled by Maoris 700 years ago. While the early European settlers set up a whaling station and camp at Wellers Rock on the peninsular in 1831 we pitched our little tent in Portobello in 2017. This quiet rural location was close to Dunedin while at the same time just a short car journey from Fort Taiaroa at the outer tip of the peninsular. This fort was built in the 1880’s when Britain was sabre rattling with Russia and the threat of a Russian invasion here was thought to be real. It never happened but on the centenary, when big celebrations were to be held, someone forgot to invite many tallships and the only one who could make it at very short notice was, yep you guessed it, Russian. They finally got their Russian invasion albeit small and very friendly. We met a couple of connections while half Maori Mary was showing us around. W.G. Armstrong was one of those brilliant minds of the Victorian era who was as adept at Garden and House design as he was at business and armament manufacture. He invented the Disappearing Gun and one was installed here in 1889, to keep those Ruskies at bay. It rose up out of the ground on a hand pumped water and air system and returned itself to the pit by the sheer force of the recoil. One factor troubled me. Given the brilliance of having a gun painted green to camouflage with the surrounding grass; what happened when the grass turned brown? Rob has visited Armstrong’s Garden at Cragside in Yorkshire and I studied his house and garden in my OU Arts Degree. Many years ago and I have no idea where, a young lady named Barbara kept nagging her dad to convert to Christianity. He became so sick of this that to shut her up he chopped off her head. So Saint Barbara became the patron saint of those facing sudden death in general and gunners in particular. She was the reservoir of much praying as the soldiers toiled over the gun here. Mary called me forward from the group because she saw I had a camera. “Make sure the flash is on and take a shot down the barrel,” sounds dangerous I thought. The end result showed the inner core of the gun was spiralled to increase the accuracy of the fire. Since then the tiny NZ bird with the delicate chittering song and the tail feathers that fan out as it flies were named Fantails after Armstrong’s Gun. As Mary led us up to the gun emplacement which is now the lookout for the high fenced Royal Albatross Colony Reserve on Taiaroa Head, she paused and turned towards the hill ridge along the side of the reserve. She pointed out where her family have lived over many generations and some still do. Mary retires this month, March and plans to visit the UK, Shetland islands and Avignon with her English husband. She spoke with immense pride about the 70 years of continuous research, protection and conservation that is being managed at the Nature Reserve by the D o C, Department of Conservation. How necessary is this protection with the ever increasing numbers of Albatross drowned in long line fishing, a predicament so easy to avoid with the use of weights to keep the lines well under water until near the fishing boat. We watched one uncertain and reticent albatross toddle off down a grass path, away from its nest, towards the cliff edge, harassing a female sitting on her nest on the way. With baited breath we were united “Will he fly, oh no he’s changed his mind.” He opened and flexed his wings a few times and then, when we had almost given up, off he leaped with such grace, embracing his natural element and soaring out to sea. If he was an adult bird he will be among the 85% of adults who return to this spot after two years. If he was a young bird his first circuit of the South Pole will take four years before he returns with 75% of his fellow young birds. On the same day we were looking forward to returning later to the Reserve to view the little blue penguins who come ashore every evening to their nests, but first we would have some lunch and a look around the little museum in Portobello that is sited in an old settlers house complete with outbuildings. Another fascinating account of the lives of the settler families through photos and artefacts. In one of the outbuildings that housed domestic and farming machinery, on the wall, was an advertisement for Nitrate and Phosphate fertiliser dating back to 1870. So the tragic pollution of the once pristine rivers with cattle waste and the leaching of these chemicals out of the ground and into the water courses started 150 years ago. It is surprising how quickly a river can recover under proper management and at last the problem is well known and understood, so hopefully the right action will be taken to clean up the rivers. Our little crowd, standing on the fenced and elevated platform, lit from underneath so the penguins couldn’t see us, did not have long to wait for the arrival of the troop of thirty or so penguins. They had to run the gauntlet of marauding seagulls to make it to their well paddled path into the thick grassy area and their nests. It was impossible to get perfectly sharp photos of them as the shutter had to open up and take longer to close than normal to absorb enough light in the near dark conditions, so they were invariably blurred, or ‘soft focus’ as I prefer to call it. One little chap was convinced there was something up there and stood by our platform for ages staring up at us staring back down at him/her. We were not allowed to let any light come from our cameras, either flash or light meter red as it could damage their eye sight and frighten them. We should not have been there really, any of us. Enriched by our proximity to such special little creatures we wandered back up the steps to the sounds of their grunting happily as they settled down for the night. Their biggest predators are possums, dogs and car tyres so we drove very carefully back to camp |