A Day with Tyronne Bell an elder of the Ngunnawal Nation

|

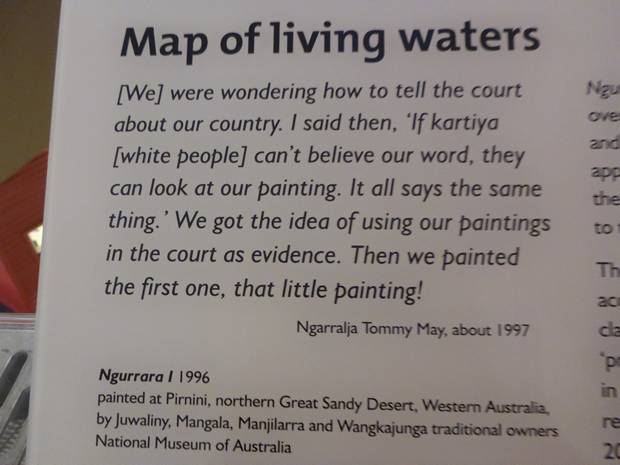

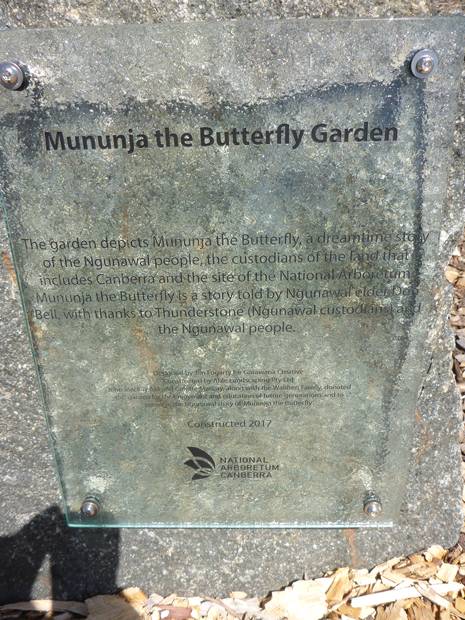

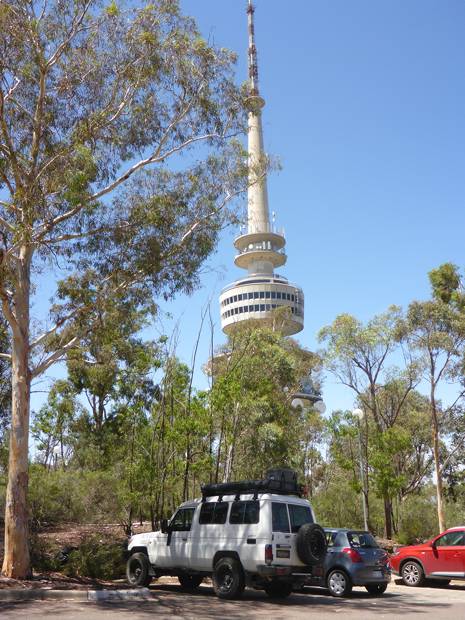

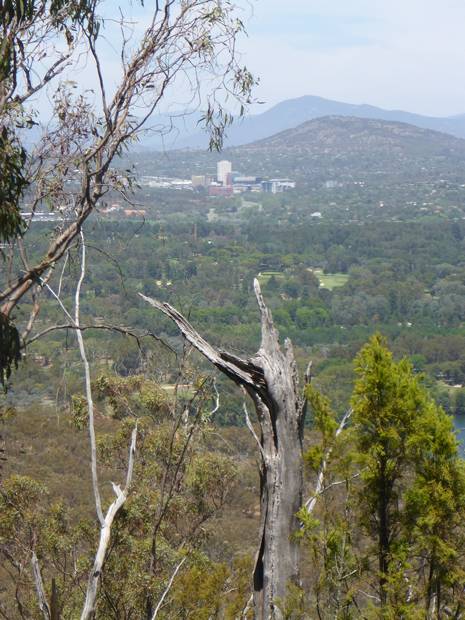

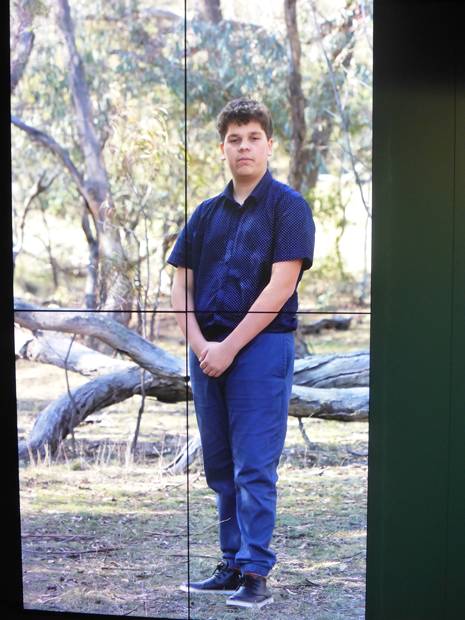

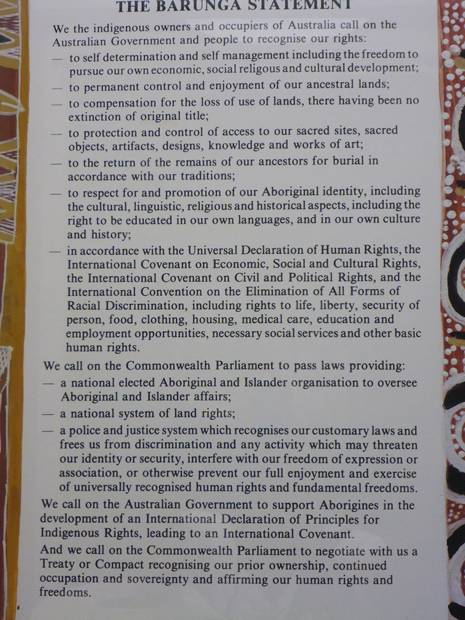

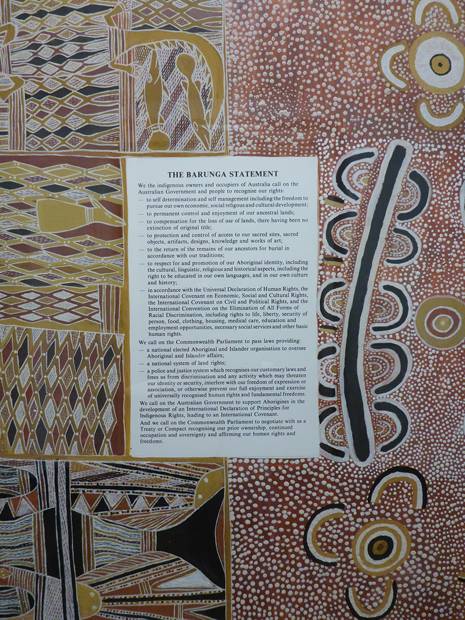

A Day with Tyronne Bell An elder of the Ngunnawal Nation We sped along the Tuggeranong Parkway towards the Namadgi Visitor Centre, Rob and I perched on the rear side seats of the white UT you can see parked beneath the Telstra Tower on Black Mountain and Tyronne driving while at the same time telling us about himself and his struggle for recognition of his nation within the conservative white man’s (bananda) corridors of power in the nation’s capital. Tyronne’s great grandmother was a native princess who met an English explorer whose name eludes me. This gentleman told the princess he could not have children, however his untruth was revealed when she gave birth to Tyronne’s grandmother. In time Tyronne’s mother was born just as the first white men and women started arriving with cases full with missionary zeal. This young girl was one among the thousands of aboriginal (bininj) children taken literally from their mothers’ arms and raised the European, mostly British way in missions many miles from their homes. ‘The Stolen Generations’ they became and this misguided form of ethnic cleansing continued until well after I was born. Eventually Tyronne’s mother went back to her tribal lands to find her family and when she did they didn’t want to know her as she was no longer seen as one of their family. Imagine the heartbreak. The historic destruction of existing populations and cultures by invading colonialists in favour of European religions and social and political systems is a characteristic of the migration from the crowded Europe to the rest of the world, isn’t it, and Australia is no exception. As we are learning more by the day the Aboriginal culture of Australia is now thought to have been in continuous existence for over 65,000 years and they have much they can teach us about environmental management for example. During times of year when the undergrowth is moist aborigine farmers conduct cool burns which can be easily stopped and burn just the undergrowth leaving the trees unharmed and with blackened trunks. This allows animals to escape and means they never had to endure the massive and destructive fires that have become a part of modern day life. We had arranged a visit to Namadgi to take a short walk in ‘Country’ with Tyronne and visit the Yankee Hat Rock Art site. The weather had been unusually hot and dry and was getting hotter as we parked the vehicle and Tyronne told us about some of the plants in the visitor centre garden and their aboriginal uses in medicines, cloth making, weaponry, food and the grass straw that Rob is blowing creates a whistle that attracts snakes so they can be killed and eaten. Tyronne had explained that despite the fact he was taking us to a National Park on his nation’s land he had to collect a gate key from the office before driving to the rock art site. Although title to many areas of land distant from Canberra has been given back to the rightful owners the government then passed a law that says Aboriginal business cannot be run on private land. So the National Park land had to be leased back to the Australian Government in order that the aboriginal clans can run the Parks. But here white people were running the Visitor Centre and Tyronne did not possess his own key. “I’m really sorry but the park is closed due to the risk of fire so we cannot let you in today. I was going to phone you as I have your number but …..” I could feel the tension and frustration this caused Tyronne. He now had to rethink our day in a situation that was out of his hands. He had sensed we were passionate about the state of modern day aborigines so we set off for a short walk near the Lanyon historic homestead to see two cut trees, the bark of one tree would be carefully peeled off and used as a canoe and the central vertical layer of the heart of the other trunk would be made into a shield. We talked all the while about how funds destined for the use of Aborigines on their many projects to restore their nation are often misdirected and disappear and how when the Canberra government want advice about aboriginal affairs they go far afield and avoid using the wealth of knowledge that is right beneath their noses. The day was dry and hot and the ground dusty and hard as we walked to the Lanyon homestead where we joined a tour with a family of grandparents and two grand-daughters. We had already looked at homesteads and this is not what we wanted for the few precious hours we would have with Tyronne, so I asked if we could move on to our next destination, the arboretum. A relatively new venture in Canberra’s desire for a place of excellence on the world map the reason we went there was to see the garden designed and created by Tyronne and his team with the help of an English designer who has worked on both Chelsea gardens and designed for the Queen. “Ah you’ll soon be asked to design a garden for the show Tyronne” I said quite seriously. When we were in the National Museum of Australia the day before we had found Tyronne was very prominent and while he declined having his photo taken on the day I had fortunately got one in the museum along with the words you see in the pictures by his father Don Bell and his uncle Wally, both great advocates for their people. Culturally the aborigines are finding success and retaining their beliefs and way of life in many ways because many non- native white Australians and visitors are genuinely interested in these modest but fascinating people. The little garden is laid out like a butterfly shaped in grass. “Better seen from the air would you think?” Rob asked. Tyronne had to negotiate hard with the management of the park, who are generally suspicious of him, to let him fly his drone over it and take some photos. From there we moved on to the Black Mountain with the Telstra Communications Tower on the top. A sacred place where the spirit people live amongst the rocks. “We are the people of the rocks,” he explained. “This is the meeting place of the men where we have always met to entertain visitors, discuss all matters national, celebrate, initiate our young men into adulthood and bury our dead.” The tower was built without consent and in the process bones of the ancestors, when uncovered, were secretly disposed of so the building process was not delayed. I reflected on how for decades in the UK archaeologists survey and study sites of previous occupation for posterity and very publically, think Matthew Flinders at the new Euston Station site, and then treat any remains with due respect. “I am arranging a meeting with the Telstra management,” Tyronne went on to say, to find ways of righting some of these wrongs and working together for the future. I hope they listen and agree because such unions can be very beneficial to both sides. Telstra’s public relations could be advanced along with a greater understanding of Bininj history, rights and beliefs. We set off on a two hour walk around the mountain just below the tower in 39’ heat, wearing our faithful hats and sunglasses long sleeved tops and trousers as protection from the sun and biters. Fortunately we stopped frequently so we could learn more. Across the plains were other mounts and Tyronne pointed to the womens’ meeting place from which men were excluded and where apart from the obvious communal and domestic activities, women gave birth with willing and experienced hands to help them. Hundreds of clans would gather together on the shores of the Molonglo River on the flat limestone plains. Their meetings peppered with feathers of smoke rising from cooking fires. Noisy, colourful days filled with activities including ceremonies, feasts, dancing, marriages using their sophisticated arranged marriage methods, (more about that later) and so on. We stood with Tyronne looking down towards modern Canberra which is built on this ancient meeting place and we saw freeways, empty areas of sculptured park and introduced trees (5 million according to Michael our tour guide in the culture bus) bold, grand civic buildings, expressions of colonial success and power but we failed to see any evidence of community, instead numerous middle class suburbs where the well healed and government employees lived in material comfort and voluntary social isolation. I wondered if there was anyone in Tyronne’s family who would be carrying on with his good work. Just in passing we had mentioned we visited the Cook exhibition and Tyronne asked if we had seen his son doing one of the welcome speeches on a large vertical video screen to the right of the entrance. The person we saw was too old to be his son so the next day we went back to the library to investigate and see the immersive light and sound experience film showing some of Australia’s natural beauty through the eyes of Joseph Banks. Sadly only the second half of the film was about Joseph Banks but it was enjoyable. What we did see was his young son giving a warm welcome to all-comers so I took the photo for you to see. We had mentioned to Tyronne that we would be back in Zoonie towards the end of the year and he suggested we keep in touch so that next time he will take us onto his National Park and show us where and how his family and clan have lived for thousands of years. We welcomed the invitation and in parting outside the YHA he pleasantly surprised me with a kiss and hug goodbye. Full to overflowing with what we had learned that day, only the essence of which I have written here, tired and sweaty we both had cold showers and then ‘broke back’ and ‘crook foot’ hobbled around the corner to Shorty’s Bar for some contradictory White Rabbit dark amber ale and tasty supper before losing ourselves in a good nights sleep.

|