2020 Aus Early Kojonup

|

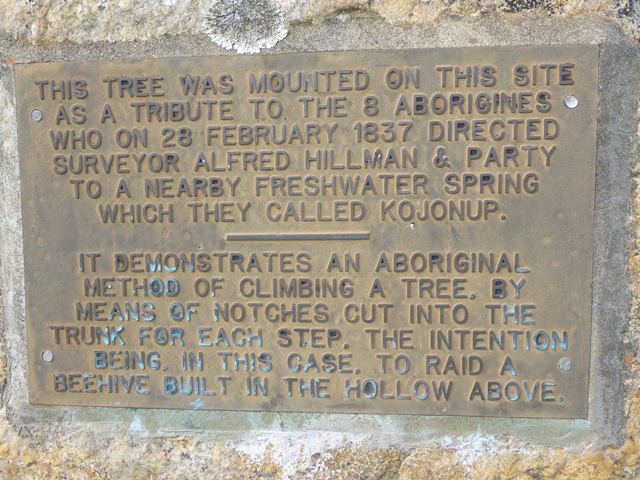

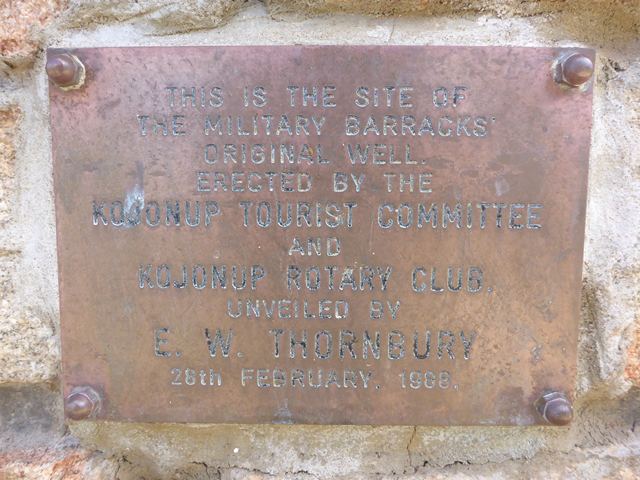

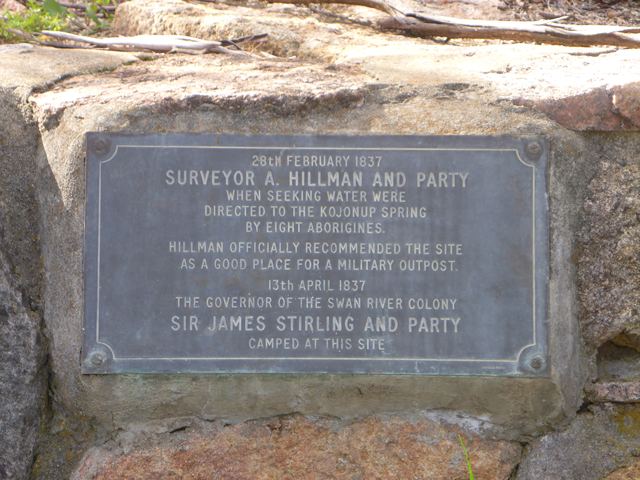

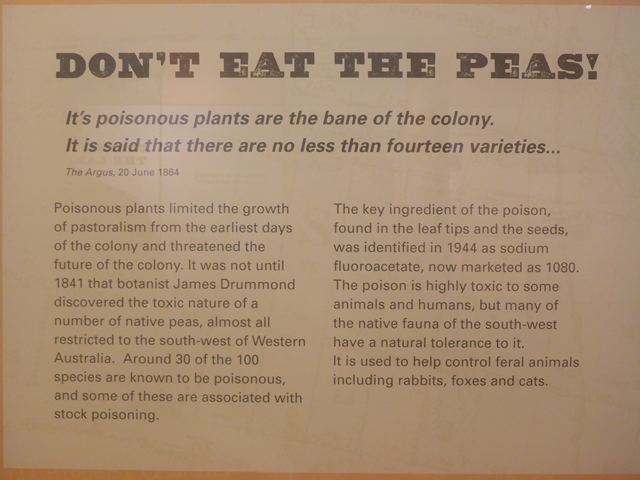

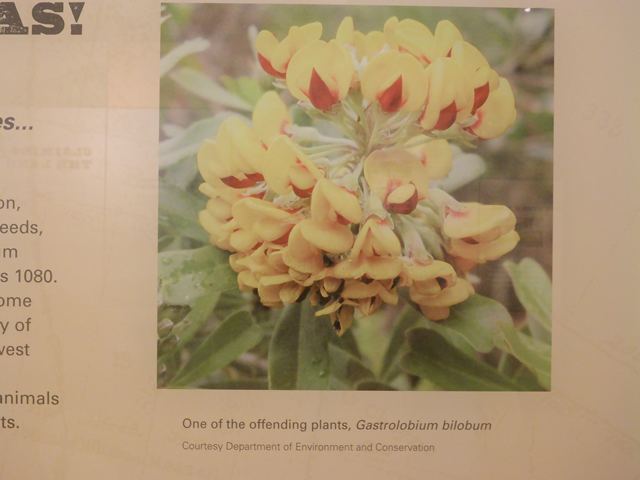

Early Days in Kojonup One fine morning in February 1837, by white man’s calendar, a group of eight Aborigines were walking stealthily through the lush green countryside of South West Australia, ‘The Great Southern’ towards a waterhole where they hoped to find some wildlife drinking which, using their hunting skills would provide their next meal. Just imagine the mutual surprise and cultural astonishment they will have felt when they stumbled onto a party of white men, led by Surveyor Alfred Hillman, who were marking the road that would lead from King George Sound (Albany) to the Swan River (Perth). The party had spent the previous night at a lush green spot but found no water there. So they were grateful to these aborigines who gave them the exact location of a spring of fresh water a few miles away. Hillman was so impressed with the site of this permanent spring he wrote in his field book, ‘This would be a good place for a station.’ I took the photo showing all green foliage underneath a log grating, as that is supposed to be the spring; there certainly was a trickle of water bubbling up and flowing through the plant-life. The name Kojonup probably originates from the Aborigine word for a long handled axe or ‘kodja’ and ‘norp’ meaning ‘plenty’ and the first part was most likely given to them by those same eight aborigines. There is much hard quartzite rock in the area, known as Kojonup Sandstone which flakes into razor sharp edges, ideal for a cutting instrument and early settlers found numerous axes around the land suggesting that this could have been a factory area for making the axes that were then traded with other mobs and tribes. Early relations with the generous aborigines were good with friendly guides helping the newcomers find their way around. They cannot have known of the intentions of the white men to claim the region in the form of large tracts of arable and livestock land that would be bought by settlers. Dissatisfaction was abounding that the coastal plains were not as potentially productive as the rich grasslands of the interior; and the common view was that sheep would thrive and be profitable. Before any of the obvious benefits of this road linking growing settlements on two different coasts and opening up the entire south west could be enjoyed it was considered essential to build a military barracks there to protect travellers, mail carriers and immigrants intending to settle and farm the area. Hence the photos of the second barrack building, the first having rotted away with the help of termites and ants after just a few years. The soldiers were a detachment of the 21st Regiment known as the Royal British Fusiliers and may well have joined the army because it offered security and a regular income, while the civilian alternative in the rapidly industrialising homeland was mostly an impoverished and uncertain existence. They lived on meagre rations of salted meat, pease and rum, plus what they could make using flour and salt, but soon they were learning wildlife hunting skills from the generous local ‘dark hunters’ who also imparted their long held knowledge of the nearby countryside, its soil, plants, water supply, animals and trees. When, two years later the regiment departed for duty in India some of the soldiers remained in the colony, happy with their situation and willing to pursue the dream of a new life. As the season turned through the year the newcomers could see just what a fertile area this was; with grass growing aplenty and up to one’s hip the grazing potential was limitless. In September 1840 the Government held a public sale of 17 different tracks of land around Kojonup marked off in blocks of 640 acres and by 1842 the sale of what amounted to this stolen land was concluded and the farming future for the investors and settlers assured. Or was it that easy? Of course not: like childbirth the growth of a new colony and township was fraught with pain, sudden disaster, joy and tragedy, not the least of which was the York Road Poisonous Plant of the pea family a member of the lobelia species that decimated the early attempts at pastoral farming by killing the grazing animals. The photo is from the picture of one we found in the Amity Museum in Albany. The toxic poison was identified as Sodium Flouroacetate and it is still used as the commercially branded 1080 in New Zealand to control non-native pests, amongst much opposition from concerned groups and individuals of the thinking public. NZ imports it from the USA.

|