Fw: 2020 Aus Bessy and Archie

|

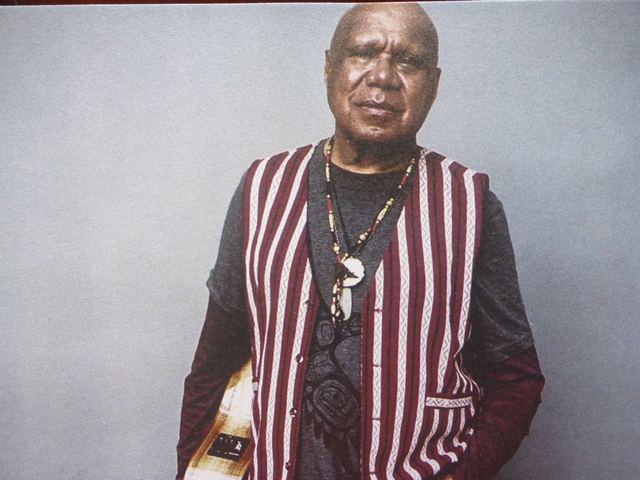

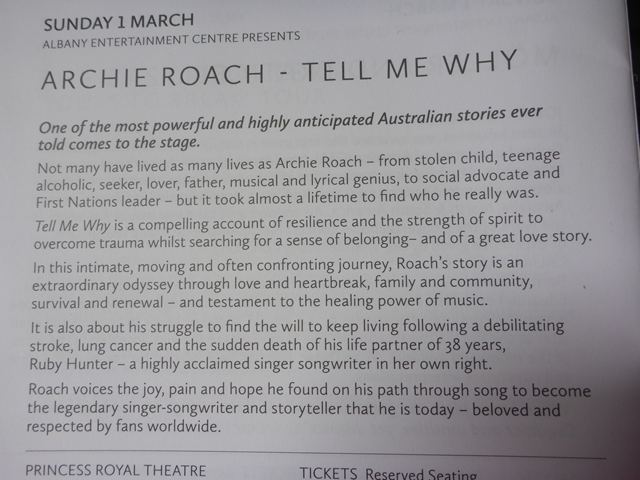

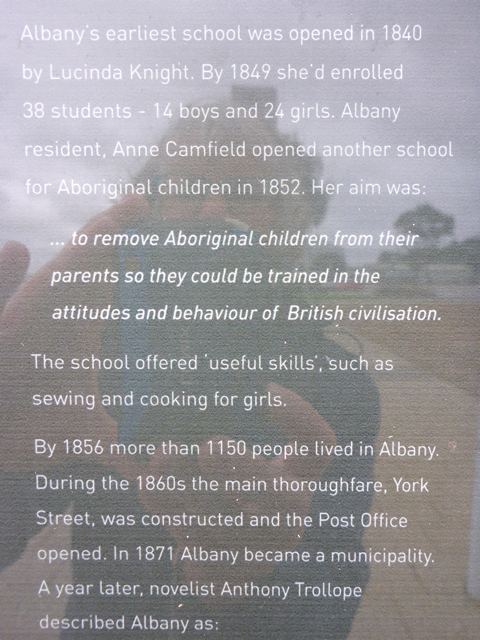

Bessy Flower and Archie Roach Advocates for the First Nation People of Australia Bessy’s parents were two of the aborigines I mentioned that were absorbed into the newcomers life in Albany. They worked for Henry, a government representative and Anne Camfield in the new town. Anne set up a school for aboriginal children where she organised lessons that would make young aboriginal girls useful servants but soon after Bessy joined the school she realised she had an extremely talented young lady on her hands. Bessy was not a stolen child herself, in fact she joined the school after her father died. So it may have been something of a relief to her mother that she would be receiving an education where she herself was working. Bessy blossomed at the Camfields’ School and it is testament to Anne’s broad outlook that she had the skills to educate Bessy beyond the schools limited remit for girls. Quickly grasping the English language in spoken and written form she was equally conversant with French and enjoyed not only fiction but also history and travel and more serious works of literature. She was an accomplished musician of the keyboard, playing the harmonium and later the organ and a talented singer. From 1866 for a year she was the salaried organist at St. John’s Church which we visited twice. All Anne Camfield’s young girls grew to be well educated ladies, quashing the idea that first nation people were ignorant savages but in a sense Anne had created ladies who were an ill fit in the new society with its limited perception of the role of aborigines. Some of the ladies married local white men with tragic outcomes that can only be imagined, so Anne tried to find them aboriginal husbands by sending them to missions in the eastern states where the first nation men had been Christianised. So at the young age of 16 Bessy left Albany never to return. On board the ship that took her and her lady charges to Victoria, Bessy played chess with the Captain of the ship and later, in Victoria she beat the Victorian champion at the game. She worked at a Moravian Mission at Ramahyuck in Victoria teaching both aborigine and white settler children. “I have begun school in great earnest,” she wrote to her friend and mentor Anne, “We sing, say catechism…. write in copy books… read and say the ABC …. They are quick in learning and obey me quickly”. Bessy also ran evening classes for the young men and was governess to the children of the mission superintendent, Frederick Hagenauer. One of her most demanding teaching roles was to prepare the pupils for the public examination and a very surprised school inspector, having marked the papers reported that this was “the first time that 100 percent of marks had been gained by any school in the colony.” Bessy married Donald Cameron who was half aborigine and carriages full with well-wishers from all around descended on the mission to join in the celebrations. They were both busily and happily employed at the mission, Donald running the farm and overseeing building works and Bessy, through her literary skills and contributions raised the opinion of the Aboriginal people’s intelligence in the wider community. She became a prolific letter writer, supporting local white and indigenous people to government level including the mission superintendent, Hagenauer and writing frequently to the Board for the Protection of Aborigines, until in 1886 The Half Caste Act changed everything for the couple and their eight children. With Donald being only half Aborigine they had to leave the Mission and their eight children behind and were forced to live in a hostile settler community. From then on Bessy fought hard to have her children back, her efforts were frequently rejected but she never gave up, fighting later on behalf of her own children to stop her grandchildren joining the ‘lost generation’ as well. The secretary of the board in charge of this decision was, ironically, the superintendent of the mission himself, Friedrich Hagenauer and I fail to see how their estrangement from their children ever happened when Bessy’s dedication to raising them as children of the new culture was so dedicated and effective. The emotional drain on her was great and the frequent disappointments were harsh. Although they were allowed to visit the mission and she at least knew where her children were the whole tragic process wore her down and she died of peritonitis at the age of 44 years while visiting one of her daughters in Bairnsdale (ironic that the name ‘bairn’ is Scottish for child) where she is buried. Although gone she was not forgotten and is remembered today by her descendants and in the literary and cultural life of south and west Australia. The ‘Write in the Great Southern’ is part of the Perth International Arts Festival and in 2013 a book about her was launched at the festival. Bessy is also recognised and remembered with the Bessy Flowers Scholarship, an award presented to high achieving Noongar students. I may have mentioned Archie Roach in a previous blog. We first heard of him in a radio interview while he was promoting his final tour, his autobiography ‘Tell Me Why’ and his latest album of the same title. Naturally I downloaded his book into my Kindle library and read it and the other day Rob earned mega Brownie points when he returned from town to Zoonie with the news that Archie was appearing at the Princess Royal Entertainment Centre on the quay, five minutes away from Zoons, the following Sunday, would I like to go? Archie was wheeled onto the stage in a borrowed wheelchair and sat half on a high stool while his pianist was to his right and the guitarist and double bass player were behind him to his left. With a low gravelly, weary voice he unfolded to us the story of his life interspersed with songs from his latest album of the same name. As he sang his own songs, his voice became energised and combined with his speech emphasised not only the pain and struggle but also the love he shared with one white couple who raised him and with his lifelong partner of over thirty years and sadly no longer with him, Ruby Hunter, a talented singer songwriter herself and the first aborigine lady to have her own album released. Unlike Bessy, Archie was one of the ‘Lost Generation’ but now lives with his children and an ever-changing group of youngsters who need a helping hand in life in Victoria. I felt privileged to be in the audience listening to his story and his songs were powerful and inspiring too. Although they were born 105 years apart Bessy and Archie have both been instrumental in the ongoing fight for equal, humane and fair treatment of their own people.

|