Melbourne aboriginal art

Melbourne Art Gallery had an aboriginal art display. Obviously all modern since they didn’t have paper and paints, although they did decorate the coffin logs – see below – but these all rotted away. Really good because they gave insight into some of the aboriginal tribes verbal history – the dreamtime. This is the ancestral being Wuyal, the sugar bag man, of the Marrukulu tribe carved by Durndiwuy Wanambi (1990). Wuyal established the Marrakulu peoples land and laws and named various important places and animals / plants. In search of honey Wuyal felled a Stringybark tree (a type of eucalyptus), from which the first wild honey flowed. The felled tree formed the Gurka wuy river. On his travels Wuyal saw many possums and so he is associated with possums. The Marrakulu hold the possum as a sacred animal because of this association.

This is a portrait of Wulwuma (the yam spirit ancestor) carved and painted by Jason Guwanbal Gurruwiwi (2009). He is decorated for ceremony with sacred body designs, lorikeet feathers and a ceremonial headband and is being guided by Guk Guk. Wulwuma carries a woven dilly bag full of yams and has his digging stick in his hand. The colour of his body is the same as the earth from which the yams are dug. Wulwuma’s feathers represent yam flowers and his hair the yam leaves.

These are larrakitj painted with stylised wet season rain clouds and birds silhouetted in white. The zig zag pattern represents the sea.

This is a Bunya Male ceremonial pole (2011) by Bob Burruwal. This one is from the northern Territory, decorated with masses of orange parakeet feathers. These poles are used in initiation ceremonies of young men and can only be made by two knowledgeable men in the tribal region.

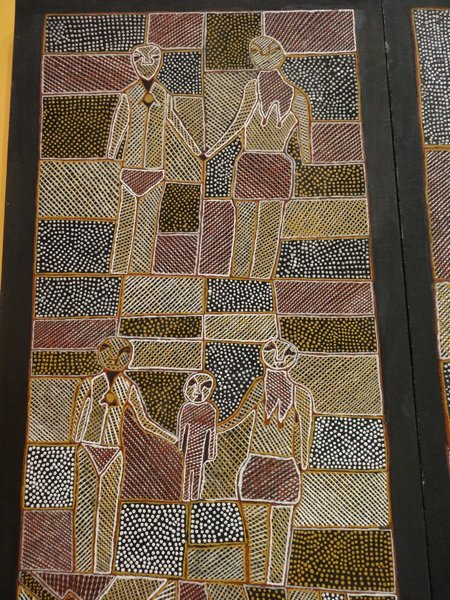

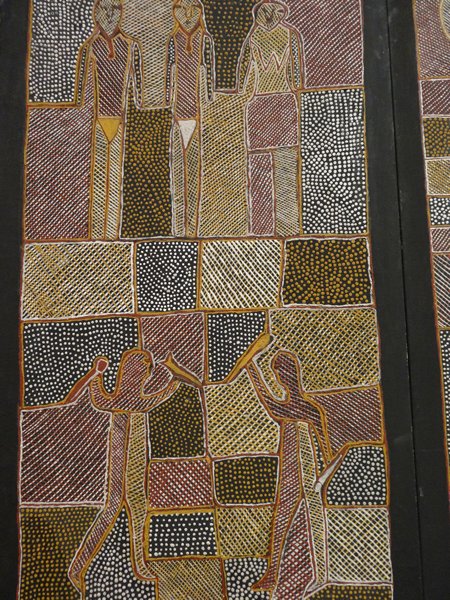

This picture show parts of the Wagilag Sisters story (Dawidi c. 1960). The two sisters travel from their home in south east Arnham land to the north central coast. They make a camp at Mirarmina waterhole which is the home of the rock python, Wititj. One version then goes that the younger sister pollutes the water hole which arouses Wititj from his sleep. She then gives birth, which annoys him even more. Wititj emerges from the waterhole and creates a storm cloud above it with lightning and thunder and rain that washes the sisters into the well. The land is flooded as the first monsoon pours down its rains. Frightened the sisters perform dances and songs but Wititj is not amused and enters the waterhole and swallows them and their children up.

This picture is called Goanna Story (Ray Munyal, 1987) and depicts another version of part of the Wagilag Sisters story. The sisters are shown in the middle of the picture dancing around a sacred well / waterhole at Mirarmina. The egg like shapes with long thin lines coming off them represent itchy caterpillars, and these surround the sisters. Goannas surround the caterpillars. In this story the sisters caught and tried to cook goannas after they made camp at Mirarmina, but the goannas came back to life and leapt back into the water hole. Meanwhile along comes the rock python, Wititj who swallowed them and in so doing created the wet season. Wititj later regurgitated the sisters and they were revived by the itchy caterpillars.

This is Ngalyod (the rainbow serpent) by Les Mirrikkurriya (1987). The rainbow serpent is associated with water in which she lives and is responsible for the growth of water plants like lilies, vines, algae – you can water plants in the picture. Waterfalls are said to be her roar and the large holes in stony river banks and cliffs are her tracks. She is held in awe by native peoples because she can shed her skin. The white ochre used in the painting is said to be her pooh. Love it!

These are Lorrhon (hollow coffin logs). They are decorated termite hollowed Stringybark logs. They are the last in a sequence of mortuary rituals. Bodies are left in the air to be consumed so that only the bones remain. These are then placed within the decorated log which has been painted with clan designs. These are then placed into the ground and they slowly decay. Thus everything returns to the earth. Aboriginal clans would have done this for centuries but nothing remains of the artwork since all decayed. This one comes from the Northern Territory and was painted in 2002 by Samuel Namundjdja. It was covered in stylised skeleton heads and bones.

This is a stylised representation of the hollow log ceremony (Djalambu by Lipundja, 1964). The spirit of the dead person is represented as a catfish moving downstream seeking the sanctuary of shady waterholes. The catfish needs to avoid being caught by diver birds plunging into the water. You can just make out the bird in the bottom of the picture. Unfortunately the bird does catch the catfish with its soul and eats it, picking the bones clean – representing the flesh rotting off the dead. On the LHS is the hollow log in which the bones are placed it looks like it has two eyes! When the bones are placed in the ‘coffin’ ceremonial dances are performed and long bullroarers (bull rushes), representing the diver birds in flight, are twirled above the dancers heads – can’t see that myself. Well I think the bullroarers are the black and mustard triangular things with red fringes. The dancers could be holding shields which are pointed at either end – see below.

These are all ceremonial shields used by aboriginals and constitute some of the oldest in Australia, despite the oldest only being about 230 years old.

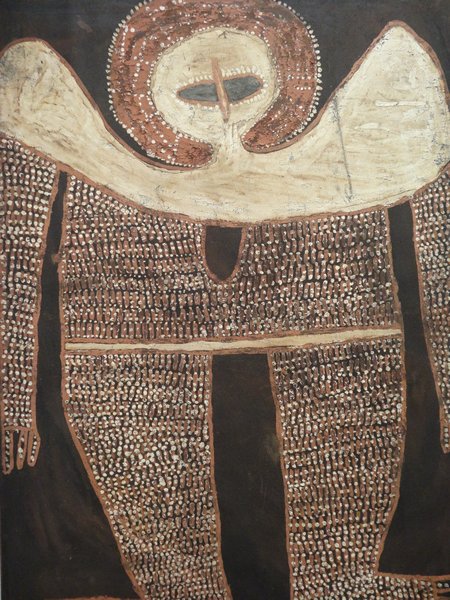

This is Wanjina – which is a generic term for the sprit ancestors of the Worroma, Ngarinyan and Woonambi people of the Northwest and Central Kimberley’s. Here Wanjina is represented in human form. It is believed that the Wanjina left behind paintings of themselves. These paintings were inspired by Wanjina images with high pointed shoulders that are found on rock art in the Lawrey River area. Painted in 1980 by Alec Mingelmanganu.

These are Mimih sprits by Crusoe Kuningbal (1984), who was the first Kuninjku artist to make these painted wooded figures. The Mimihu are said to have taught ancestral Kuninjku peoples their culture – their laws, ceremonies, hunting, survival etc. in the rocky escarpment territory in which they live. They were incredibly long and thin. Apparently images of long skinny Mimihu abound on rocks in the Stone Country, south west of Maningrida – can’t wait! Here’s head and legs with the long thin body missing!

This tells the story of Purrukuparli and how death came to the Tiwi people. Ancestor Purrukuparli and his wife Wayayi had a son called Jinani.

While Wayayi was out collecting bush tucker for supper she was enticed into the trees to make love with her brother in law, Taparra. She left her son in the shade but was away so long that he dies of sunstroke. Her distraught husband, Purrukuparli, was so enraged that he fought Taparra, hitting him with spears and throwing sticks.

Taparra was seriously wounded and became the Moon Man, thus always reminding the Tiwi of the life and death cycle (full, no, new moons). Purrukuparli then picked up the body of his dead son and walked out into the sea leaving his wife Wayayi in the bush alone. Wayayi became the curlew always crying her grief at dusk – the curlew are in the bottom picture. Meanwhile before Purrukuparli died he taught the Tiwi people how to conduct a proper mourning ceremony. Since then whenever someone dies the Tiwi paint their bodies, make burial poles and armbands, and dance the dance of mourning.

Paul looking happy as I made him wait for lunch so that we could go on aboriginal talk – which was tack as the bloke was rushing off somewhere else. What we did glean is that the dot art that you see everywhere originated in the mid-1970s. Apparently the government decided to try to educate the aboriginals and one of the art teachers just gave his students paper and paint and told them to paint, but not how to paint. The dots resulted.

|