Tongan Weather Adventures - Pangaimotu Island, Tongatapu, Tonga

Harmonie

Don and Anne Myers

Thu 4 Jun 2009 09:27

|

21:07.588S 175:09.819W

Tongan weather is known to be somewhat

unpredictable. The wind can change 180 degrees and whip up to a frenzy in

a matter of minutes, unleashing nasty storms with all those things a boater

hates - extremely high winds, pounding rain and above all, lightening.

Last year, in all of our travels, we ran into lightening only once in the

tropics, and that was during a four hour storm we hit while sailing from

the Tuamotus to Tahiti. Even then the lightening was far away and not

really a threat, which was good since the two tall masts on our

boat might look tempting to the odd bolt of lightening passing by. In

general, nasty storms and particularly thunder and lightening storms are rare in

the tropics. However, Tonga happens to sit in an area that is often on the

edge of what's called the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ). We

don't claim to understand all the particulars, but we do understand that the

result of two large air masses converging above our heads is often not

pretty. This meeting of air masses and potentially stormy weather

happens quite often in Tonga resulting in the general weather pattern which is

described in all the guide books as 'five days of settled weather and

consistent southeast trade winds followed by ten days of unsettled weather and

winds from every direction occasionally accompanied by storms'.

The good news is that with all the weather information available today via the

internet and long range radio, we usually know when unsettled weather is coming

- it's just a matter of how unsettled it will be. Even without the

internet and radio weather, a gander at the sky and some level of attention

to wind direction trends usually tells the story. Again, it's just a

matter of how bad the unsettled weather will be. If the wind direction is

predicted to move 180 degrees or even 360 degrees, then astute boaters will

make sure that the site they have chosen to anchor will still provide

shelter in all the expected wind directions. This isn't always easy

given that some island groups just don't have anchorages where shelter

is provided from more than one or two wind directions. In this case,

boaters do what we've done over the past two weeks, plan island hopping

travels through Tonga based on the weather forecasts. If we know a west

wind is coming and there is no nearby anchorage with protection from the west,

then we'll move on to an island and anchorage that does. If the

weather is severely changeable and we are in an anchorage with decent protection

from several wind directions, we'll wait out the unsettled weather and not

leave until the sun shines again and the wind swings back to the

southeast.

Our first encounter with unsettled Tongan weather

happened when we and the rest of the rally boats were still anchored off tiny

Pangaimotu Island. It was the day after the big pirate party and things

were mighty quiet until about noon when the wind started to pick up. At

this point, the wind was coming from the northeast and the island along with the

reef stretching off its coast sheltered the closely packed boats fairly

nicely. As the afternoon wore on, the wind increased as did the tension

aboard most of the anchored boats. We all knew a wind shift to the west

and high winds were coming, we just didn't know exactly when it would happen and

exactly how high the winds would go. We assured ourselves that the

wind shift would happen some time in the evening and the winds would only go as

high as 30 knots (~35 mph). The sun went down at six and the wind started

gusting consistently to 25 knots. Why is it, we often wonder, that the worst

weather always happens at night? And why does it happen when we are

anchored in an area where the water is 20 meters (~60 feet) deep? The rule

of thumb when anchoring is that the water depth to anchor line deployed

ratio should be at least 3 to 1 in very calm conditions and as much as 7 to 1 in

a wind storm. Unfortunately, when the water depth is 20 meters, a 7 to 1

ratio, or scope as it is called, would mean we'd have to deploy 140 meters (~420

feet) of anchor line. In an area where there are 20 boats tightly packed

and all at anchor, deploying 140 meters of anchor line is not possible for two

reasons; many boats don't carry that length of anchor line, and with so many

boats packed in a relatively tight space, boat collisions could easily happen as

all boats would be swinging around their anchors in very large arcs. In a

water depth of 20 meters at Pangaimotu Island, most boats, including

Harmonie, had about 80 meters of anchor chain or a combination of chain and

line out, which meant only a 4 to 1 scope at best.

Six-thirty arrived and the wind increased,

regularly gusting to 30 knots. We decided to postpone dinner until the

worst of the storm passed. Since we believed the worst of the storm would

be 30 knots, we figured we wouldn't have long to wait. Seven o'clock

arrived with higher winds - 35 knots. Shortly thereafter, the expected

wind shift from the northeast to the west happened. This was no gentle

breeze slowly making its way around the compass. Oh no, this was a mighty

shot of freight train wind that flipped immediately from northeast to northwest

in the space of a few seconds and at a speed of 47 knots (54 mph). The

mighty puff of wind in itself was bad enough, but the accompanying change

in direction in combination with boats with less than desirable anchor line

scope deployed on a sloping sea bottom resulted in immediate chaos for at least

six boats in the anchorage. Forget about dinner, we scrambled to turn on

all the instruments, the computer, electronic charts, the engine and the

lights as we squinted into the darkness through the sideways rain shouting

at each other over the roar of the wind about which boats were dragging,

where they were going and if we were in danger of getting hit. It was

about then, as the wind continued to gust into the high 40's that our anchor

alarm went off indicating that we were dragging. The feeling was

like being on one of those rides at the fair when you lose your stomach as

the contraption plummets in unexpected directions. When our anchor let go,

we could feel the movement and it was fast. I immediately fell into

military mode, asking for orders from the captain, 'Tell me what to do!' I

yelled. 'Motor forward! Don bellowed back. It was about then, after

our (mostly my) 30 seconds of panic that we realized the anchor had caught

again and was holding as the wind and rain continued to pummel us.

Later we realized we had dragged about 50 meters, half a football field,

in less than 15 seconds. For the next three and half hours,

Don was stationed at the wheel, with all instruments on and motor running while

I stood in the cabin watching all the instruments to be sure we weren't dragging

again. It felt and sounded like we were sailing. The boat was

bouncing up and over wind waves as they smashed on the bow and we were surfing

fast side-to-side as the anchor strained and the wind pushed hard.

Boats that dragged and continued dragging had

to pull up anchor, weave their way through the crowded anchorage between

boats wildly surfing side-to-side in the relentless wind, with zero visibility

in the pounding rain. Zero visibility except for the ever increasing

flashes of lightening that is. The next day Jackie from Lady Kay told

us she was incredibly grateful for the lightening as it gave her flashes

of visibility as she piloted Lady Kay through the anchorage

after she and Michael pulled up their own

dragging anchor.

After about three hours of this ordeal, with Don

still positioned at the helm and me still staring at the instruments, a new

threat emerged. In between lightening flashes, Don noticed a very

large vessel leaving the Nuku'alofa harbor and heading straight for Pangaimotu

Island and our chaotic anchorage. Several other boats noticed the same

thing and immediately got on the radio warning the large vessel off. For

about an hour various boats tried calling what looked like a dilapidated Tongan

ferry boat on the radio to ask them to leave the anchorage, but to no

avail. The Tongan ship never responded to the radio calls and took up

residence in the roaring wind and rain perilously close to several of us

that were located on the outskirts of the anchorage. The wind

continued to howl and we worried not only about wayward sailboats grazing by us,

but now the possibility of a giant ferry boat grazing by us as

well. Ten thirty arrived and the wind finally backed off to less than 35

knots, but the rain and lightening continued. We decided it was finally

safe to eat dinner and scarfed down a quick sandwich while continuing our

stationary watch. A little later, the wind backed down below 30 and Don

left his post for bed. As per usual in this kind of situation, I was too

jumpy to sleep and stayed up the rest of the night watching and waiting for the

wind to dissipate even further. At seven in the morning the wind

relented and dropped below fifteen knots. Time for

sleep.

The next day I asked Don what he would have done

differently had he known the wind was going to be as ferocious as it was.

He said he would have put out more anchor line and had two of our largest

fenders (dock bumpers) ready at the bow such that if we dragged and didn't stop

he could have simply cut the anchor line, tied the fenders to the severed end,

and instructed me to motor us out of the anchorage leaving the anchor behind for

retrieval the next day after the storm passed. He figured this would have

been the quickest way to get out of the anchorage without hitting another

boat. If we had to pull up the anchor, it would have taken too long and we

would have continued to drag into dangerous places during the process.

Next time we'll be more prepared.

Less than two months into our second sailing season

and we have already broken the highest wind while sailing record once and the

highest wind while anchored record twice. Hopefully that's it for record

breaking for a while.

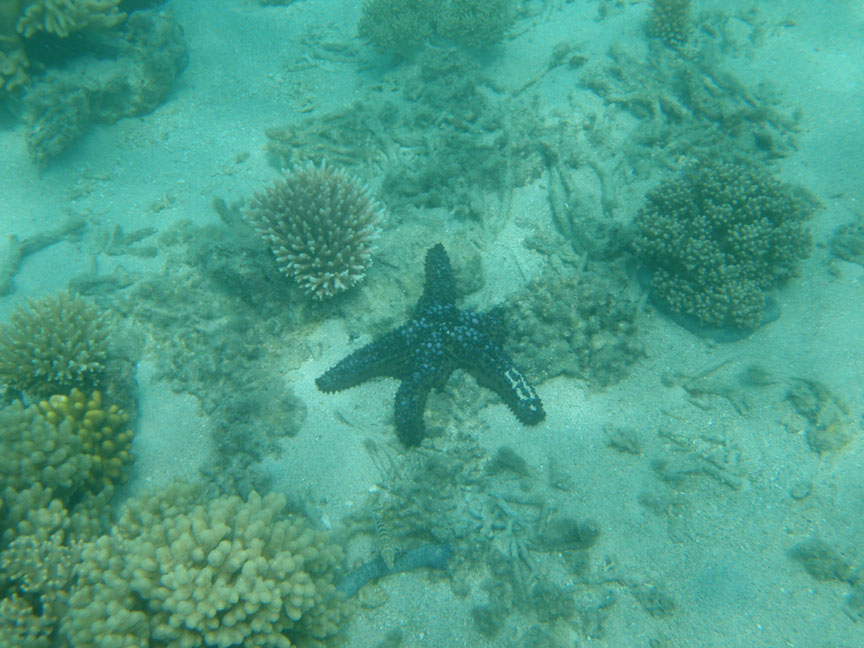

On the bright side, we did have a few days of nice

weather during our stay at Pangaimotu Island. Good enough to go snorkeling

and try out our new underwater camera. Picture 1 is one of the gigantic

blue/black starfish that are common in Tonga. Picture 2 is the coral reef near

the island with a few tropical fish tooling around including our favorite tiny

iridescent blue variety. A few days after the big storm we were greeted by

the incredible full rainbow in picture 3. Unfortunately I couldn't quite

get the whole thing in the frame, but it was the most beautiful rainbow we have

ever seen. Both ends went straight down into the water and were reflected

there so that the rainbow continued on over the water's surface.

Amazing.

Picture 4 is the sailboat that arrived in Tonga

from New Zealand a few days after we did. Obviously they encountered some

of that famously ugly New Zealand weather along the way, which decimated

their head sail. The typical response when the rest of us sailboaters see

a sight like this is, 'Wow. Glad it wasn't us.' Not too sympathetic,

but indeed, perfectly honest. To add insult to injury, this boat's anchor

got hooked on an old ship's anchor and chain lying on the bottom and they were

unable to haul their anchor until divers helped them disentangle it. The

good news is that they were hooked on the old ship's anchor and chain throughout

the big storm and didn't drag. Like all things in life, there's usually a

bright side. It's just that some bright sides take a little more effort to

find than others. We didn't talk to the people on this boat, but can only

guess that they weren't necessarily ready to admit there was a bright side just

yet.

Anne

|