Pacollo

Caramor - sailing around the world

Franco Ferrero / Kath Mcnulty

Tue 5 Sep 2017 02:13

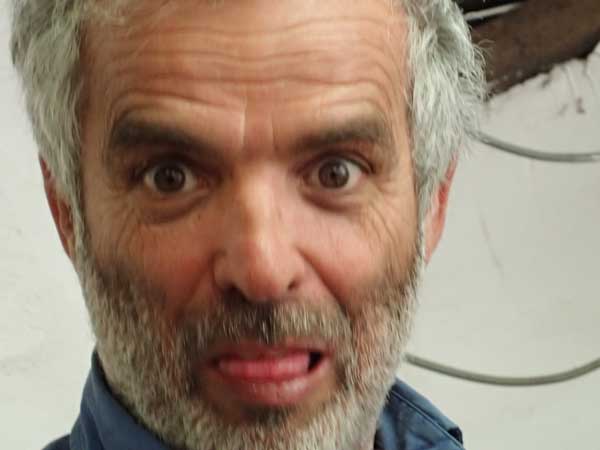

16:08S 69:55W Our route to Pacollo followed the metalled Pan-American Highway to Bolivia, as far as the village of Acora where we turned off onto a dirt track. We zigzagged around potholes and forded rivers for the next two and a half hours, driving across the vast altiplano. A small boy, Giovanni, came to greet us and once he got over his shyness we became great friends. His mum Silvia and her partner Eustacio look after the land for Santiago. The lad was alone most of the time, looking after the cattle. We were surprised there were no other kids around and even more so to learn that the school had been shut for the past two months because of a national teachers' strike. I trusted him with the camera and over the next four days he took some interesting shots. At first his framing wasn't great but with time he learnt to choose his subjects and settings. He quickly realised that pictures taken into the sun didn't work out and by the end he was a proper little 'paparazzo'. Most of the photos that follow are his.  Giovanni Pacollo is Santiago's family home. His father got a job as a teacher in Chucuito, this was before the road to Bolivia was constructed. Every Friday evening he would ride his horse home, a journey that took him five hours. Then on the Sunday evening, he would ride back to the shores of Lake Titicaca. The last time he undertook the journey was in 1963. Since then, Santiago has ridden the route but it took him ten hours because properties have been fenced and new roads put in.  Pacollo When we arrived, there was no water so Giovanni went to fix it. The water would go off several times a day so Giovanni took me up to the stream to help him repair it. The pipes were attached together with a plastic bag so each time a cow walked past or the wind picked up, they would come apart again. Eventually Franco and I duck-taped the joint. It might not last forever but at least we didn't need to go up to fix it again.  Giovanni’s favourite calf Every morning we went to work early on the new shelter for the horses. In addition to Santiago, Eustacio and Silvia, there was Ruben, so Franco and I made ourselves useful however we could.  The structure The conversation was in Aymara and we couldn't understand a word. This is the language spoken by the Aymara people, an indigenous nation that live on the high plateau that spans Bolivia, Peru, the north of Chile and the north-west of Argentina. The Inca conquered, the Inca fell, the Spanish came, then mobile phones but nothing has changed very much, what happens in Lima doesn't seem very relevant.  Ruben  Walking back to the house One to five in Aymara: 1 - maya 2 - pailla 3 - kimsa 4 - poussy 5 - presca  Giovanni in front of Eustacio’s Dodge  The pig - eats rubbish then gets eaten Santiago disappeared off for a few hours. When he returned he explained that he had been to see the local 'mago ' (medicine man). In Aymara culture these people are very respected and their role is much wider than healing. A solar panel and some tools had gone missing from the house and Santiago was hoping the 'mago' would be able to tell him who had taken them. The 'mago' gave him a name and Santiago paid this gentleman a visit. He hopes that the goods will be returned and that there will be no need to involve the police.  Giovanni’s portrait of Franco  Giovanni spying on Kath In 1969 the Peruvian Government initiated agrarian reform. Land was seized from the large landowners and redistributed to the peasants. Although compensation was supposed to be paid, this seldom happened and claims are still going through the courts today. National production dropped drastically at the time and the horse all but disappeared from the countryside but at last the people were working for themselves rather than for slave wages. Unfortunately, it seems the benefits were short lived; the holdings are too small to be viable in the modern world and many are leaving for the cities to find work.  Santiago hammering Santiago was cooking delicious food for us all. It was amazing how much our friends could eat, even young Giovanni. I told the story of the first tiramisu (my signature dessert) I prepared for Franco and how he had told me he had tasted better in Edinburgh! (Not that I hold grudges, you know.) Santiago served up spaghetti and homemade pesto and turned to Franco: "As long as you don't tell me you've eaten better pesto in Bolivia!" We all laughed.  Santiago cooking I offered to prepare the next meal. My rice disintegrated and blended together before it became soft, I couldn't understand why. I thought it was the quality of the rice until Santiago explained it was because of the altitude and that the only way to cook starch is in a pressure cooker.  Silvia milking Another man turned up, he looked like he meant business and within a few hours all the corrugated sheets were up and nailed into place. Back at the house it was celebration time. A bottle of rum was mixed with coca-cola and handed to Franco with a plastic cup. Franco looked around: "Where are your cups?" he asked Eustacio and Ruben. "I'm not drinking alone." They giggled and said nothing. After about half an hour, Santiago who was busy cooking turned around. "What's up? Why aren't you drinking? Franco, you're supposed to fill the cup, drink and pass it on!" Franco looked at Eustacio. "Ruben never speaks to me," (everybody giggled, even Ruben, because Ruben never speaks to anyone) "but you Eustacio, why didn't you tell me?"  The structure is progressing  Giovanni self-portrait  Giovanni’s portrait of Kath The sun was beating down. Franco and I were in shirt sleeves. Santiago was still wearing his woollen jacket but Silvia, Eustacio and Ruben were wearing at least three layers of wool. We stopped for lunch. Eustacio said "It's so hot!" But still he didn't remove a layer. Franco pointed out to him that he could take some clothes off. They all thought this was very funny. Eustacio acknowledged this as a possibility but remained fully clothed.  Sunset over the altiplano  Franco and Kath In Pacollo, there is only one tree, it is just outside Santiago's house. With his father he planted many trees but none survived. One afternoon I walked up the hill to the cliffs at the top of the slope. In the least accessible cracks there were bushes growing. If the cattle, sheep, llamas and alpacas were removed, I bet trees would colonise. I walked up through a breach in the cliff, to the summit. Beyond was more altiplano, it seemed to go on for ever. I returned a different way and scrambled down the bed of a stream and eventually dropped through a crack in the cliffs.  Santiago’s house with the only tree  The altiplano from the top of the cliff  Pacollo from above  The other side of the hill  The cliffs (I returned through the crack in the centre of the picture) The sink had blocked but Eustacio and Silvia were going dancing. I decided to fix it so Giovanni showed me how.  Giovanni showing off with the chainsaw The highest village in Peru is at 4,500m. It is inhabited by miners. They work six days for the company and one day for themselves. Santiago tells a story: "One day, one of these miners, a simple country lad, makes an offer to buy a farm worth US$ 200,000. The farmer who is selling isn't sure whether to take him seriously. He makes enquiries with the bank. The manager informs him that sure enough this gentleman can afford to purchase the farm, he has US$ 460,000 in a savings account." It would seem that some miners do strike it rich.  Santiago doing Peruvian carpentry  Just the ridge missing It was Sunday. The horse shelter wasn't quite finished, the ridge was missing. No work would be done today so we packed our bags and headed back to Chucuito. Giovanni came with us, Anya had a bicycle waiting for him.  Playtime: Giovanni with his mum looking on  Flowering cactus |