Santo André and the Pataxó Indigenous People

Caramor - sailing around the world

Franco Ferrero / Kath Mcnulty

Fri 19 Jun 2015 18:24

Porto Seguro claims to be the first Portuguese town on the South American continent founded in 1526 after Cabral's landing nearby in 1500. Today it is a prime tourist destination for Brazilians and sounded just like the sort of place we weren't interested in visiting ... until we read about the Pataxó Indians.

Pataxó Indian approaching a village

Porto Seguro (meaning safe harbour in Portuguese) is no longer accessible for deep keel boats, the closest option for Caramor was 20km north at Santo André.

Santo André is a small friendly, slightly alternative village on the João de Tiba river. Although the entrance is fairly straight forward (using the Brazil Cruising Guide and a good electronic chart), it is not for the faint hearted. The approach involves sailing between coral reefs with the surf breaking three miles out at sea and then slaloming between a double reef, a sandy spit and extensive sandbanks. We went in on a rising tide two hours before high water and at times Caramor had all of 40cm under her keel. Once in though, the anchorage was so calm we forgot we were on a boat.

Coral reef protecting the coast

Santo André anchorage

I wanted to meet the Pataxó. How had this group of people, living so close to the site of the first Portuguese landing, managed to preserve their culture for over five hundred years? How does a community in modern day Brazil maintain a separate culture and customs?

In 1997, three Pataxó sisters decided to return to their roots, build awareness of their culture and live in the forest as they had done before their father was assassinated by a large landlord. They founded Jaqueira, a village on the edge of the Mata Atlântica. This was where I wanted to go. All I knew was that it was 12km from Porto Seguro.

Online, I found Pataxó Turismo, a small company which offers tours to Jaqueira. I emailed them, phoned them, no answer so on the Sunday we set off for their offices in Porto Seguro.

The cruising guide says there is a bus. We paddled the twenty metres to shore in Ding and walked down the dirt track through Santo André to the metalled road. We waited by the side of the road for a bus which arrived, by chance, five minutes later. The conductor said it went to Balsa, not Porto Seguro. The woman sat in front of us took us in hand, she was tour-guiding a couple on their second honeymoon after 28 years of marriage. They were from Paraná, the state south of São Paulo and they instantly befriended us. Balsa, it turned out, was not a village. It means 'raft' and is the ferry to Santa Cruz Cabrália. During the crossing, our new friends showed us their holiday snaps; Him and Her on a beach, Him and Her under a palm tree, Him and Her by the hotel pool, Him miniaturised and stood on the palm of her hand, ... They took a photo of us, we have probably been shrunk and put in a bottle.

The 'balsa'

From Santa Cruz, our guide had ordered a taxi. There is a bus to Porto Seguro but it is infrequent and only fractionally cheaper than a shared taxi.

The 20km road to Porto Seguro runs just behind the beach and is lined with hotels, B&Bs and restaurants, mass tourism with most wallets catered for. People come here in the summer for the nightlife.

As we sped along in the Berlingo driven by our guide's future husband, we passed a woman on a motorised long board skateboard. In her hand she held a black object with a trigger; the skateboard controller, (not a gun as we had thought in Ilhéus!).

Porto Seguro was like any bad taste seaside resort in the winter. The small historical buildings along the front have all been turned into shops selling tourist tat. The few open restaurants were expensive for the standard fare and Pataxó Turismo was shut. We didn't stay long.

Porto Seguro

On the way back, as we passed through Coroa Vermelha, the last village before Santa Cruz, we saw, stood by the side of the road, a half naked man wearing feathers on his head and face paint. He was deep in conversation with a lady pushing a bicycle. I wondered whether Jaqueira was close by.

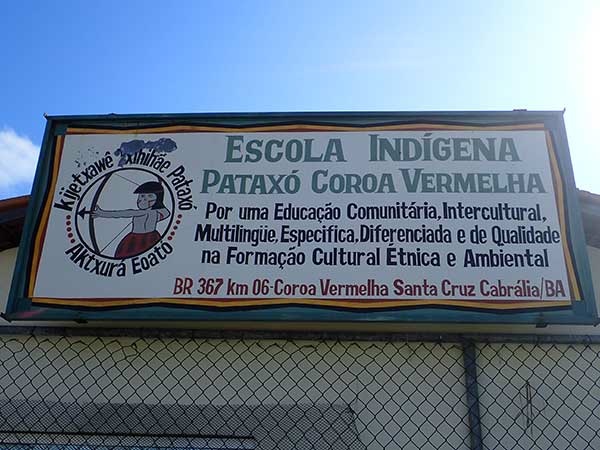

My options for visiting Jaqueira were running out. The village didn't appear on any map we had seen and I had no directions for getting there though some of the notes I had found online seemed to suggest a link with Coroa Vermelha. The next day I set off on my bike for Santa Cruz hoping to find a tourism agency which could help. There weren't any. In a last ditch effort I decided to cycle to Coroa Vermelha on the off-chance I would find some clues. By the side of the road I saw an Indian school.

Indigenous School

The young porter was very helpful. He made a few calls on his mobile and said he knew someone with a 'quadriciclo' who might be able to take us to Jaqueira. A fleeting image of a motorbike with a four person side-cart flashed through my mind. "How many of you want to go? Come I'll introduce you to the teacher." Her name was Claudia, she made a call and passed me the phone. The man on the other end said "yes, no problem". I was struggling to understand him so I handed the phone back. Details were finalised, we would meet Roberto outside the school the following morning at nine.

That evening we went out for dinner in Santo André and found a lovely restaurant called 'Almescla', the name of a medicinal plant from the forest. We were the only diners and the food was delicious. The owner joined us for a chat. She is from the Porto Seguro area and her husband from Vitória. She told us that she is very busy from just before Christmas until Carnival and that the rest of the year is pretty much dead. In the winter she takes time off to go travelling in Brazil.

Sunset over the João de Tiba river

The next morning we caught a shared taxi to the school. Claudia greeted us, she was wheeling a motor-scooter. A few minutes later, Roberto arrived ... on a quad bike.

Franco turned towards me accusingly, "you never mentioned a quad bike!" "Details, details" said I, though I was as surprised as he was! I suppose I should have guessed that 'quadriciclo' meant quad bike though I had thought the conversation had moved on to a more conventional form of transport. Roberto was no easier to understand face to face. He gave Franco a three seconds quad bike training course "you push here, here and here. Shall we go?" I was puzzled, "how are all three of us going to fit on that?" He pointed at his transport, Claudia's scooter.

After a few hundred meters on the main road, we turned off down a dirt track. Franco had got up to third gear and Roberto was impressed.The ride was bumpy. At first there were houses along the track, many were round, made of concrete, with thatched roofs. They gave way to a degraded landscape, bare dusty earth with scrub, the odd pile of rubble or rubbish. It looked like the land had once been forested. Shortly before arriving at Jaqueira, in places the dust had been planted up with seedlings.

Roberto left us at the edge of the forest where we were met by a young Indian who led us to the village. In 1998, after a 24 year campaign, Coroa Vermelha was declared 'indigenous land' and granted the management of 827 hectares of Mata Atlântica. This became the Jaqueira Reserve and is where the three sisters relocated and built a traditional village. The main objectives are cultural affirmation and environmental protection. It has become a catalyst for indigenous culture and a model for sustainable eco-tourism. It is a symbol of resistance for the Pataxó people. Thirty-two families now live here. The remainder of the 11,800 strong population live in ordinary Brazilian towns and villages and dress as any other Brazilian but Jaqueira provides them with a link to their culture and traditions.

We were introduced to Uháy Pataxó who could speak Spanish and was keen to use it. This worked well for us as it meant he spoke a little slower. Uháy told us about Jaqueira, the Pataxó and a little about himself. His mother is Pataxó, his father isn't, which means they cannot live in Jaqueira. His mother had her first child aged 14 and and all three by the age of 19. Uháy is 18 and the middle child, he has been living at Jaqueira for the past six years but visits his parents in Coroa Vermelha almost daily. Education is very important. This is in sharp contrast with Brazilian society where, on the whole, education isn't valued. Getting ahead is important but this is done through 'jeitinho', meaning 'little way', the Brazilian version of 'where there's a will, there's a way'. Uháy has just started a degree in chemistry, he hopes he will be able to put it to use helping his people. He went away for three months to learn Spanish on an intensive language course. He also speaks Portuguese and Pathxôrã, the Indian language spoken in Jaqueira.

The Pataxó see themselves as custodians of the environment. They are pragmatic, they are not trying to exist in isolation, instead they make the most of modern Brazil while at the same time retaining their native culture. Both men and women can become leaders (cacique). The Pataxó were hunter-gatherers but today they can no longer hunt for food as wildlife is very rare and protected. As they do not want to depend on government handouts, they have set up an eco-tourism project to inform people about their culture. All the money is used to buy food for the community. They wear both Indian and modern clothing. Their schools teach Pathxôrã, Portuguese and English, science and other standard subjects as well as Pataxó culture.

Uháy told us about marriage which can be initiated by either the boy or the girl. The declaration is made by placing a pebble at the feet of your chosen one. If it is accepted, there is then a three months' courtship. The match has to be approved by the village elders rather than the parents. Young people may marry as young as twelve but the boy has to undertake two tasks to prove that he will be able to support his family. The first involves hunting a wild animal on his own in the forest. As this is no longer possible for environmental protection reasons, instead, once a year, all the prospective grooms chase a pig through the forest. The second task is to carry a large log for a specified distance.This symbolises his ability to support a wife, and ensures the young man is physically mature enough.

The face paint designs are personal though married people wear two parallel horizontal lines across the cheek whereas single youths draw a zigzag pattern. The colours are red, black, yellow and white and are from natural materials.

To live in Jaqueira you have to be at least half Indian. If you marry a non-Indian you will be expected to move away. Cooking is communal. There is a primary school in the village but the secondary school is in Coroa Vermelha. The oldest person in Jaqueira is 96 years old, she was cooking when we visited and is a role model for the young people. No doubt she can remember the era before the worst oppression.

Kamarú, Kath and Uháy

Uháy introduced us to Kamarú who took us for a tour of the village. The tree nursery includes plants that will be planted out to restore degraded land and plants for medicinal use. The Pataxó use both their own herbal medicine as well as western allopathic medicine.

He told us the names and the uses of the trees we passed. One species, Plathymenia, can grow so large that it would take five people holding hands to surround it. In the past it was used to build dugout canoes, now no longer allowed.

The Patioba palm (Syagrus botryophora) leaf has many uses. Patoxó warriors communicate in the forest by hitting the stem with a lump of wood which makes a loud dull sound that carries for many miles. It is also used in cooking; food is wrapped in the leaf and then grilled, keeping the food moist and adding flavouring. This palm copes well in sandy, nutrient-depleted soils and is being used extensively to restore deforested land.

Fish grilled in a patioba leaf

We walked through the forest to the Lagoa Seca (Dry Lake). After two or three days of rain the dip fills with water and becomes populated by fish. Once the water level drops, the fish head off into the forest to look for water elsewhere.

Kamarú and Franco at the Lagoa Seca (dry when we visited)

Along the path Kamarú showed us the kind of traps and snares the Pataxó used to hunt game. I recognised many of the techniques as ones used in Wales.

Snare

The school was lively with children studying English. Some teachers wore the traditional palm skirt and finery while others wore trousers and t-shirts.

Jaqueira primary school

At the end of our tour we were treated to Pataxó cooking.

Franco enjoying 'fish à la Pataxó'

My private make-up artist

Life for the Pataxó has not always been this peaceful. Records (Casal, 1976) suggest that they were once a very numerous nation living across a vast territory. In 1861 most indigenous people in the Bahia region were captured and put in a reservation at Barra Velha with the aim of integrating them.

By the 1930s, their population had dwindled with the few remaining groups living along the Contas river which flows from Chapada Diamantina down to Itacaré. Douville (Douville & Metraux, 1930) explains that their population had been decimated by smallpox which had been maliciously introduced by a Brazilian Colonel responsible for subjugating them. Douville describes them as naked, with painted bodies, long hair and a pierced lower lip and ear lobe with a piece of bamboo inserted into the hole.

According to Nimuendaju (1938), they did not practice agriculture, weaving, pottery or make canoes. "Their containers for water and honey were bags made from monkey hides. They carried items in embira string bags." He describes their encampment "roofed shelters covered with tree bark, surrounding an open clearing in the forest with a tree in the centre around which they seemed to dance."

Nimuendaju explains that prior to 1927, groups of Indians had been gradually exterminated by local farmers. "In 1938, a single man remained of the group, who had been captured four times by the Paraguaçu Post staff and had fled three times before dying."

In 1951, the main Pataxó village was caught (deliberately, it seems) in the crossfire between bandits and the police. Hundreds of men, women and children were shot and the survivors scattered throughout the region. They weren't able to regroup and for the first time started to marry with non-Indians.

Ten years later, the Monte Pascoal National Park was created on land occupied by the Pataxó. The indigenous people were expelled and forced to survive on government handouts. Much of the land was handed over to landowners for the cultivation of cocoa and coffee.

In the early 1970s, Porto Seguro started to become a popular tourist destination. Pataxó people were encouraged to move to Coroa Vermelha to develop their handicraft production and sell to tourists. Over the past thirty years, the Pataxó have strengthened their identity and embraced education. Many have succeeded as journalists, lawyers and scientists in mainstream Brazil and are able to further the interests of their community.

Back at the entrance we found Roberto splashing around in the stream, we joined him for a quick dip. He led us a slightly different way back to Coroa Vermelha and took us to the site of the Portuguese arrival in 1500. The bay is protected by a reef, like at Santo André. A large cross has been erected to commemorate the first mass celebrated on Brazilian soil.

The cross commemorating the first mass in Brazil

The beach huts must have looked inviting back in 1500 after a long ocean crossing!

We stopped at Beto's Bar for a drink. Roberto told us that he is married to Claudia and that his sister runs a restaurant in Santo André, the 'Almescla'. It's a small world!

Kath