Adventures in the interior

|

I was sitting in the shade of an acacia tree looking

across the battlefield of Isandlwana. Others of our small party were below

me, wandering among the memorials and randomly situated piles of whitewashed

rocks stretching away towards the lower slopes of the odd, sphinx-shaped hill

known locally as Isandlwana Mountain. I was thinking, as one is bound to

at this place, of the wretched futility of war. Twelve hundred men of

First Battalion, The Welsh Regiment (as it later became known) and their local

allies died on the plain in front of me as did 3,000 Zulu warriors, for no very

good reason. It was one of the most shattering defeats suffered by the

British army – certainly the most complete at the hands of warriors wielding

mostly cow-hide shields and stabbing weapons. Only 50 British soldiers

survived, all on horseback. There was no-one left to bury the dead and it

was five months before the army returned to collect up the remains that had been

left on the hard, rocky soil exposed to the weather and the depredations of

scavenging animals and vultures and to cover them with cairns of stones.

Some cairns hide the remains of 30 to 40 men, some two or three. The men

were mostly unidentified; soldiers did not wear “dog-tags” in those days.

So there they were in front of me, piles of white stones covering real bones of

real men. Over to the right on the sky-line I could just make out the mass

grave of the Zulus. It was all terribly

moving.

The mounds of stone covering the real remains of the soldiers killed at Isandlwana.

That

afternoon in January 1879 4,500 warriors of the Zulu right flank, the right horn

of their buffalo attack formation, defied a direct order from their king,

crossed the Buffalo river from Zululand into British Natal and fell upon B

Company, Second Battalion, at Rorke’s Drift. B Company had been left

behind by the main British inva ding force to look after the sick and

wounded in the Swedish mission station, commandeered by the army commander Lord

Chelmsford to provide a hospital and storage for food and ammunition. The

Zulus had been denied the opportunity of getting at the British in the morning

and were now desperate to see some action – until they had “washed their spears”

in the blood of their enemies they were not permitted to take a wife.

There had been peace for 23 years. This battle is better known to us – 139

men under the command of two young lieutenants successfully resisted wave after

wave of attacks throughout the afternoon and all night. At first light, to

the despair of the exhausted defenders, the Zulus appeared on the hill again,

but this time they withdrew, probably because they could see Chelmsford’s relief

force arriving. 17 died on the British side, probably about 500 Zulu

warriors. 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded. A later British general

took a poor view of the officers and men who defended Rorke’s Drift claiming

that they did little more than fight “like rats for their lives which they could

not otherwise save”. We formed the impression 130 years later that John

Chard, Gonville Bromhead, Colour-Sergeant Frank Bourne (the youngest

colour-sergeant in the army) and the others showed outstanding leadership, made

excellent decisions and fought with exceptional bravery. Queen Victoria

and her advisers thought the same.

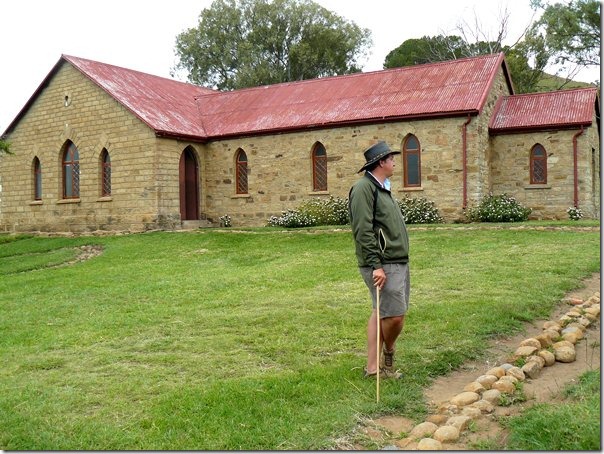

Andrew Rattray in front of the church, originally the store and re-built soon after the battle. The Rattray family at Fugitives’ Drift, where the survivors of Isandlwana crossed the river instead of reporting back to Rorke’s Drift as they should, have made a lifetime’s study of these engagements. They offer a wonderful experience from their guest lodge. Excellent lectures at the sites of the battles, by Andrew Rattray at Rorke’s Drift and Mphiwa, a Zulu, at Isandlwana were delivered with great energy and erudition, full of carefully researched detail. The service at the Lodge was relaxed but impeccable and the food excellent, not only well cooked but imaginative. It was a very British experience although it seemed that the minority of guests from other parts of the world enjoyed it just as much as we did. Every year two soldiers from B (Rorke’s Drift) Company are sent to Fugitives’ Drift Lodge for a few days to steep themselves in regimental history. At any one time there are two or three British students on “gap years” lending a hand on the estate, which is a game reserve. There is a very convivial atmosphere; drinks around the fire in the open at 1900 followed by communal dinner at a refectory table, Andrew Rattray often presiding. The main man since his father’s murder by intruders in 2007, Andrew was born and brought up in South Africa but to all appearances he is the very epitome of what we should like to think of as the best sort of Englishman abroad. When we left, reluctantly, after three nights we felt we were leaving friends. It was truly one of the very best experiences we have enjoyed in the entire voyage.

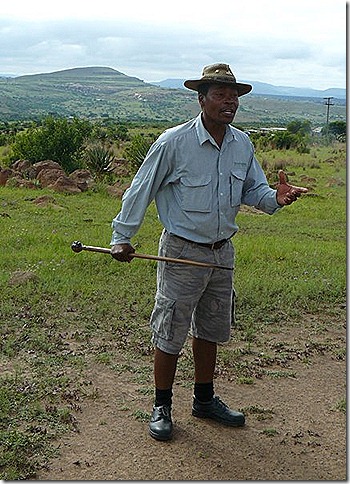

Mphiwa tells a moving story at Isandlwana and the very beautiful memorial to those Zulus who died at Rorke’s Drift. We drove on to Montusi Mountain Lodge for two nights - an entirely different experience where we enjoyed profound peace, excellent accommodation and spectacular views across grassy slopes to the northern Drakensbergs. These mountains have also played their part in South Africa’s history and there was much to see and learn as well as just sit back and enjoy.  How green is

Africa!

We returned to Richards Bay via a night in Durban in the most enjoyable

company, as throughout the trip, of Kathie and Dave from Sunflower. A

great time was had by

all! |