***UNCHECKED*** Barbuda: Then and Now

Quest

Jack and Hannah Ormerod and Lucia, Delphine & Fin

Tue 25 Apr 2017 08:32

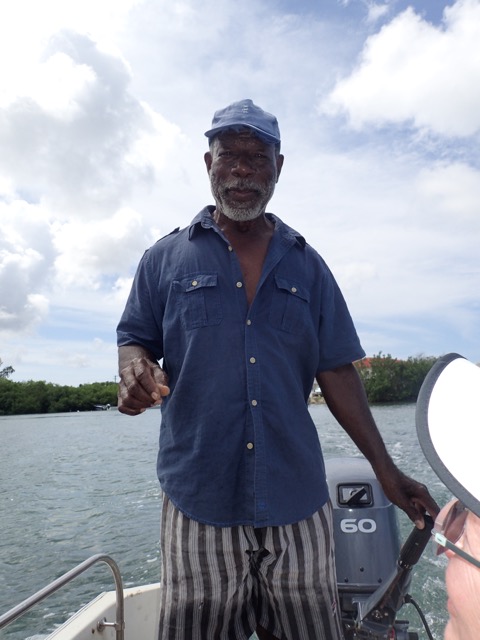

Position: 17:33.0N 61:46.9W We were thinking about the past as we drove through Barbuda. Leased from the British Government in 1688 to the Codrington family for one fat sheep, 60-square-mile Barbuda’s main role was to grow crops to feed plantation slaves on Antigua. And hunt, Dilli our taxi driver pointed out to us. We felt the lumps and bumps in Dilli’s taxi van driving along Barbuda’s unpaved road. Dilli was barefoot when he picked us up. ‘I got stuck in the sand,’ he explained. He manoeuvred his taxi around each pothole. We nodded enthusiastically. ‘Does this road connect to the main road?’ ’This is the main road,’ Dilli said. 'I came down the back road.’ ‘Aha.’ Either side of the pancake-flat land was thick brush. ‘The Codringtons shot deer and wild boar.’ 'And donkeys?’ we asked. We’d heard that donkeys inundate Barbuda. People fence their houses- not to keep animals in but to keep them out. Dilli shook his head. 'People used to use donkey to get to places. Now we call them stop signs since they like to stop in the middle of the road.’ Almost on cue, a donkey stood a hundred yards ahead. We slowed down and waited. The donkey stared back at us, bright-eyed with relish. When slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1838, because of its one fat sheep lease deal, Barbuda was left to the Barbudans. No other island in the Caribbean has this fundamental rule. This means that if you and I went to buy a property in Barbuda, we’d never own the land. We’d have to rent it from the Barbudans. Now driving along in Dilli’s taxi, the sea painted turquoise on one side and the land indented with tracks through the brush on the other, it doesn’t seem like a bad rule to us. Not a bad rule at all. We knew we’d love Barbuda before we came but we didn’t know how much. Turtles popping up the size of dinner tables in our anchorage, clear glassy water, the beach seemingly made out of powder. Barbuda was even more stunning than we realised. We knew too we had to see local guide, George Jeffrey. The Garden of Eden tour is his speciality, touring Barbuda’s huge Codrington Lagoon. The lagoon hosts the second largest frigate bird colony in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere. From October, the frigates enter mating season and the males inflate their necks into singing red balloons. Dill dropped us off at the dock. George was waiting for us. ‘Welcome,’ he said. Sarah and I exchanged glances. Was this going to be a tour with the Caribbean's Morgan Freeman? Result! Under a fierce Good Friday sun, we took our seats in his Boston Whaler boat, sweet 60hp Yammi we'd stopped to admire and were off, zooming through the lagoon’s pea-green water. All of us, including Fin (her first ever dog-friendly excursion tour :) had our faces turned into the wind. George stopped by a clump of leggy mangrove. ‘Nature has formed this place,’ he said in dulcet tones. See that sand bank?’ We stared at the peninsula separating the lagoon from the sea. A sandy stretch interrupted the middle. ‘In 1995, Hurricane Luis tore a hole in it.’ The small clump of mangrove sat in front of us like a lonely topiary bush. 'All this area was mangrove and now it’s just this.’ He chuckled. It sounded like a deep bell. 'Nature’s in charge.’ He got a rain-stained map of Barbuda out from underneath his engine and held it up. ‘Barbudans live our lives and go about our business but because we all own this land we are...’ He paused, as if looking for the right word. ‘Together?’ I offered, thinking of the Muppet song in the last (and possibly best) Muppet movie. A Russian Kermit with a mole? Genius. George flashed me a deep smile and I almost fainted to the bottom of his boat. ‘Exactly. We are together.’ As well as crop growing for plantations and hunting, the Codringtons had salvage rights too. This was no layman’s hobby since a thousand square miles of coral reef surround Antigua and Barbuda’s coast. 'And Barbuda exported people.’ We felt the weight of George’s words burning on us with the sun. ‘Men were bred here, the strongest and biggest men. I’m over six foot. My son is six, six. But that was then and this is now.’ Something of a glimmer passed through his face. 'This is Codrington’s Lagoon. Our town is called Codrington. Our dock is Codrington’s Dock. The name of our airport? You guessed it; Codrington’s Airport. There are no Codringtons here anymore. Still we name things after them. We got on well with the Codringtons. But that was then and this is now.’ It struck me that George's last sentence was possibly a well-used one. He started up the Yammi. We zoomed back through the green water, to the side of the lagoon still layered with mangrove. To the frigates. Dozens of chicks with white heads sat on sideplate-sized nests.They gurgled mouths agape as we went past. ‘Keeping cool,’ George said. The adult frigates, their heads as black as cloaks turned circles in the air above us. ‘Canadian researchers are finding that they fly to South America during the summer and back to nest in the winter.’ George turned off his engine, slipped into the lagoon and pushed us through the shallow water. Our noses took in the fruity guano air. We looked back at him. He smiled. ’No snakes or crocodiles here.' Over the side of the boat, we could see hundreds of upside-down jellyfish. ‘Do they sting?’ George shrugged, still smiling. ‘Only a little.’ It was a reluctant good-bye to George Jeffrey. Dilli met us back at the dock. He took us to Codrington’s one food store. It’s size belied that fact that it had everything you needed to live. Fresh eggs, meat, cheese the cashier cuts for you, local tomatoes, purple and white-striped aubergines. A small percentage of Codrington’s 1,500 inhabitants were wandering around its shelves. ‘Do you know where the milk is?’ I asked a lady next to me. ‘Junior, where’s the milk today?’ she shouted towards the back room. I winced but a man in an apron came out. I followed him sheepishly to the next aisle. After we stood in the line and paid for our goods, we made our way back to Dilli’s van. James, Sarah, the girls and Fin were hanging their heads out of the window. ‘Back to the anchorage please, Dilli.’ It was almost lunchtime and we were looking forward to Quest’s anchorage breeze. ‘Do you still want to buy some lettuce?’ Dilli asked. We’d been briefly to Dilli’s before the tour. He’d stopped to throw our rubbish from Quest into one of his own bins. His vegetable patch worked its way neatly in a straight line from his house. We waited as he went inside. After a few minutes, he came back out with four lettuces and a frozen bag of mixed beans and peas. He'd thrown the bag in for free. ‘From my pigeon peas,’ he explained, pointing to harvested bushes. We drove back, loving Dilli’s Easter gift, avoiding donkeys and stopping to photograph the wandering horses that are raced on Barbuda's racecourse every other Sunday. Even though we are all from somewhere, I wonder sometimes if we travel in order to search for the place we want to be from? The place where we feel we belong. Could it be Barbuda? Flat wilderness, malevolent donkeys, a fine food store and people who stand together, connected directly by their own land. And racing horses on Sunday? Right then, it was hard not to long to be a Barbudan. Impossible even. Love from Quest and her crew xx               |