Sailing Under The Stars

Sailing Under The Stars

Often, our friends ask us what we look at while we are on

passage. The perception is that all we see is 360 degrees of blue water. Well, that is true but you must realize that

half of each day is spent in darkness. When Peregrina is on passage, all of her

systems and crew are working 24 hours a day and, half of that time, it is dark,

dark, dark.

Just after the sun sets is twilight time. The definition is: “Twilight is the illumination that is produced by sunlight scattering in the upper atmosphere, illuminating the lower atmosphere when the Sun itself is not directly visible because it is below the horizon, so that the surface of the Earth is neither completely lit nor completely dark.”

Ancient cultures used to think of this time as

the crack between the worlds; the spirits of the day world exchanging places

with the spirits of the night world. When the sun sets, the night spirits come

alive. This is a picture of the sun setting on our recent trip.

We like to begin our passages during the day when possible. The primary reason for this is so that we can get the sails set for the winds and wave conditions with time to settle into our routine before the sun goes down. The second reason is that we, inevitably, forget to do a few things necessary to go to sea and the daylight allows us time to correct any tangled or misled lines, batten down unsecured items or rig the safety lines we might have forgotten in order to have a safe passage.

You see, when we are at anchor, the boat becomes a home with

books on shelves, tools on the work bench and dishes drying next to the sink.

However, when we are on passage, the books fly off the shelves, the tools

launch themselves off the work station and the dishes…well, the dishes can be

found meters away all over the forward cabin. We really don’t know how the

dishes get there! They just become alive

and move. All I can figure out is that a dish is essentially a wheel and we all

know that wheels like to roll.

So, finding and correcting all the things we forgot to do before going to sea is easier in the daytime and, even better, if we’re still be at anchor. For example, on our last passage from Grenada to Los Roques, Venezuela, I forgot to check to see whether we had batteries for the four headlamps, the two flashlights, the VHF radio, the portable GPS and the other electrical items. Ten minutes before weighing anchor, I was getting the “ditch bag” ready (this is our emergency abandon ship bag) only to find that most of our batteries were “dead”. Our departure was delayed while I jumped into the dingy to go search for batteries at a local store.

We left Grenada about 10:30am en route to Los Roques - about 300 miles away. We were headed on a course of 285 degrees magnetic with a wind from about 80 degrees. For those of you who have not done the calculations, this puts the wind just about directly behind us. When we have at least 20 knots of aft wind, as we did on this passage, I prefer to set the large genoa on the spinnaker pole to leeward rather than hoisting the main sail. This gives us the flexibility to “reef down” by rolling up the genoa and keeps the center of force well forward. This is a picture of our sail set for the trip to Los Roques.

In lesser winds, we will go “wing & wing” with the pole

on one side and the main on the other. You can see that changing course becomes

more challenging at night with all these sails set and preventers leading

forward from the boom and spinnaker pole.

As night falls, we get the boat ready for the evening

“watches.” In general, we always “reef down” to reduce the amount of sails we

have out. Our peace of mind is worth the

knot or so of speed we may lose. Next, we make sure a safety tether is

attached to the jacklines on both starboard and port. So, if someone, usually

the Captain, has to go on deck at night or when the seas are rough during the

day, the safety tether is ready to clip on to my PFD (Personal Flotation

Device) and I will be firmly connected to the boat. We keep one or two extra

tethers in the cockpit to clip into while “on watch” at night or, in case

conditions get rough during the day. We

also put two headlamps on the binnacle within easy reach. The person “on watch”

puts on their PFD and hangs a whistle around their neck to call the person sleeping

down below, if necessary.

This is a picture of me decked out for foul weather and wearing the PFD which Margie tells me I am ALWAYS to wear on deck during the night. Sometimes I listen, but I admit, because I am a Macho Man, sometimes I don’t. We seem to have a normal marriage.

After the sun sets, we turn on the Tri-Color (red/green/white) light on the top of the mast and also the running lights at the bow of the boat which indicate our starboard (green) and port (red) sides to approaching vessels.

The instruments in the cockpit are either put on a soft red color or dimmed to “night-white.” Maintaining the cockpit without bright white lights helps the person on watch retain night vision.

Down below, we change the chart table light to red, dim the

instruments and turn off all white lights in the main salon.

I prefer to listen to audio books while on watch since I can keep my night vision. Margie reads with a head lamp which the Captain does not approve of but she never listens to me. Is this normal?

Our watch system is quite simple. After making dinner, Margie

goes to her bunk from 8-10pm. She is

then on watch from 10pm-2am. I come “on watch” from 2-daylight. My watch ends

when Margie decides to arise and make breakfast. Do the math and you can easily see which of

us gets more sleep at night. (FYI -I catch up during the day.)

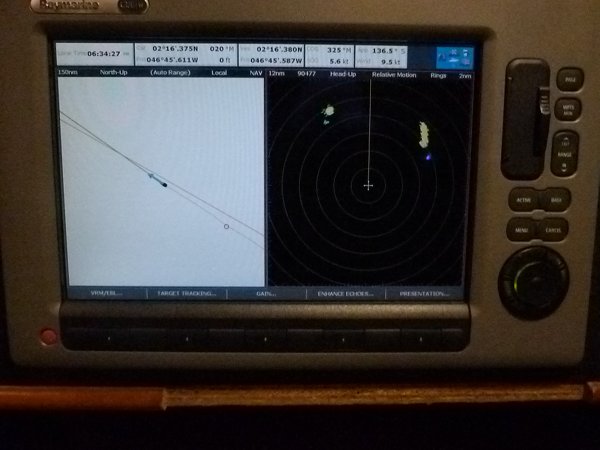

At night, I sit facing forward whenever possible to see any boats, land or obstacles in our path. We also use a split screen on the chart plotter which shows both the chart and the radar.

We keep the radar usually on “standby” and just look at a

few radar sweeps every half hour. This conserves power.

Peregrina also has an AIS (Automatic Identification System)

which provides an electronic alert that warns us of large commercial vessels

bearing down on our path. If there is a CPA reading (Closest Point of Approach)

which concerns us, we call the approaching vessel on the VHF radio. If they

answer, we tell them we are a sailing vessel, not under power, and we request

they alter course to pass no closer than one nautical mile. Sometimes they will

do this and sometimes they don’t.

The real point of my call is to see if anyone is awake on their bridge and let them know we are a small, easily-damaged vessel in front of them and nervous about having our life shortened. Once, off Australia, we had a vessel pass so close that the bow wave threw Peregrina around like a cork. We had called them repeatedly and even shined a million-candle power spotlight on the bridge but no one appeared. It must have been a good movie!

I love the night because the stars are so bright. With no land

lights anywhere, you can see stars almost all the way down to the horizon. And yes,

almost every night I see a shooting star! I make a wish with each shooting star

but I have yet to discover that Spanish treasure ship laden with gold.

Did you know that the human eye can see approximately 5000 stars at night! Staring at the sky, night after night, it is easy to see how the early navigators saw pictures of mystical animals and valiant warriors.

Do you know how we see at night? Well, your eye’s retina contains two types of photo-receptors, rods and cones. The rods are more numerous, some 120 million, and they are more sensitive to light than the cones. The 6 to 7 million cones provide the eye's color receptivity. They are much more concentrated in the central yellow spot known as the macula. Rods are not sensitive to color and, therefore, they are used more at night. The rods in your eye give you night vision. You have that many rods (120 million) so that your eye can pick up low levels of light.

Often, you can see boats further away at night than in the day, due to their bright lights. However, this does NOT apply to South East Asian fishing boats! If you are lucky, they might flick a little Bic lighter to let you know they are right in front of you but, otherwise, you must really keep a sharp lookout! It certainly made for some anxious moments back in the South China Sea! Our rods were working overtime! But, I digress…

Most difficulties at night arise when weather conditions change rapidly and we need to reef the mainsail, douse the pole or change tack. If we have a pole up, changing tack involves both Margie and I going on deck to take down our 15 foot spinnaker pole and re-setting it on the other tack. In heavy weather, this is not much fun so we try to just reef the genoa with the pole still up and make minor course changes, if at all possible.

On our recent trip from Grenada to Los Roques, Venezuela, the

sailing Gods were smiling. We put the pole up leaving Grenada and took it down

300 miles later when we approached Los Roques.

This is the island of Gran Roque as we approached at daybreak.

Another night is over and another leg of our passage complete. Our anchorage beckons us and, after a quick nap, it is on to more adventures exploring Los Roques National Marine Park in Venezuela.

--

--

--