Culion...the "Island of No Return"

Peregrina's Journey

Peter and Margie Benziger

Sun 18 Nov 2012 00:31

A Visit to Culion…the “Island of No Return”

At the end of the Spanish-American

War in 1898, the United States occupied the islands of the Philippines. It became evident almost immediately that a

medical crisis was on their hands and less than a month after the Spanish ceded

the Philippines to America, a Board of Health was created in Manila. Better health was one of the “blessings of

civilization” and the United States was determined to bring good medical

treatment to its new colonial possession.

What the authorities did not realize at that time was the extent of the

spread of leprosy, or Hansen’s Disease, throughout the country. It was estimated that approximately 30,000

cases already existed with more than 1,200 new cases developing each year. At that time, the disease was considered

incurable and the practice of segregation and isolation was the only civilized option.

Indigenous treatments of the disease

included such barbaric customs as burying the leper in a sitting position up to

his/her neck for years (!) in a hole filled with dried tree leaves, branches

and soil. It was erroneously believed

that the warmth and moisture created from the decomposing mixture was

therapeutic. Another method applied to

the cure was placing the patient inside the intestines of a black cow for a

period of two days. The ultimate tragedy

occurred when patients were buried or burned alive in a misguided attempt to

stop the spread of the disease.

In 1901, the sparsely populated island

of Culion was selected as a segregation colony and the sum of $50,000USD was appropriated

for the Culion Sanitarium.

After protracted arguments over the

estimated long term costs of the project and conflicting opinions as to whether

segregation would accomplish the goal of exterminating the disease,

construction began in 1905. The first 370 patients arrived on Culion in 1906. The following year, after the establishment

of the “Segregation Law on Leprosy,” giving legal basis to the systematic

collection and compulsory segregation of lepers in the country, another 800

patients arrived by ship. After that,

approximately 250 lepers were delivered to Culion every 2-3 months. By 1910, a total of 5,303 had been brought to

the island.

For the patients and their families

in these early years, the forced separation was really a “life sentence” and

everyone knew that they would, most likely, never see their afflicted family

member again. It was a horrible

experience for everyone involved. The

lepers fled like hunted animals or were hidden from view by desperate family

members. If discovered, they often violently

resisted arrest in a desperate effort to avoid being taken away to the “Island

of No Return” by the dreaded Sanitation Inspectors.

See below

the lament of a young boy wrenched from his family and isolated on the “island

of pain.” In the museum is the following quote written by a leper.

“I am a

leper. I was torn away from the love of my family. I live in Culion, exiled to

the island of pain. High mountains entomb me, a vast sea imprisons me; it can’t

be helped; alive or dead always. I have to be here. You, who listen, have compassion for a leper,

helping him to be healed. Ah happiness! If thus with it I recover and finally return

to my home. But if God does not give me health, I will die saintly on this

cross."

But, in truth, this was just the

beginning of a long struggle for both patients and medical science in the pursuit

of a cure for leprosy. Two Americans, General

Leonard Wood, a physician as well as a highly decorated military leader who was

appointed Gov. General of the Philippines and Dr. Herbert “Windsor” Wade,

Medical Director of the Culion Leper Colony from 1922 to 1959, would change the

course of Leprosy with their passionate search for a cure as well as their

lifelong devotion to the residents of Culion.

As a result of their collaboration and dedication, Culion Island was the

biggest, most well-equipped and scientifically advanced “leprosarium” in the

world by the 1930’s.

In the early years, Culion Island

was a dismal place. The colony was divided

into two worlds for the “leproso” and the “sano.” They were separated by a Lower and Upper

“Gates.” Those afflicted with leprosy

lived up on the hill in houses provided free of cost by the government or in

the sanitarium for those who were too ill to take care of their own needs but

conditions were appalling .

Everyone had to pass through

checkpoints at the Lower and Upper Gates and those entering/exiting the

“Leproso” section had to dip their hands and wipe their shoes in disinfectant.

Here’s Margie at the entrance to

town via the Lower Gate today. Yes, she

does have TWO ice cream cones in her hands and seems torn as to which one to

eat first!

But, with the appointment of Leonard

Wood as Gov. General in 1921 and Dr. Windsor Wade’s arrival at the hospital in

1922, conditions rapidly improved. Culion

Town operated much like any other town in the Philippines as the 20th

Century moved forward and the patients’ health continued to improve. Residents who were able-bodied, contributed

four hours per month in community service and were allowed to set up their own

Town Council and operate businesses just like anywhere else in the

Philippines. Housing improved and there

was a lovely Spanish-style central plaza where the Culion Band entertained

residents on Saturday night.

There were schools for the younger

patients and training programs so that residents could learn a trade or acquire

professional skills that could be put to use in businesses all over town.

As time went by, perceptions began

to change as those who came to live at the colony felt that, at last, they

found a place where nobody would shun them, where they could live in peace and

where they could make a living with no stigma.

As word got out that patients were provided with a free place to live,

good food, clothing and the opportunity to work at a trade, more lepers were

willing to voluntarily join the segregated colony. It was far from perfect but it was starting

to feel like home. 99% of the patients

were Filipino but a few came from countries all over the world. The

island had a steam powered electrical plant that provided 24 hour service,

operated by an American patient.

And, just like any community, there

was a hierarchy of economic and social strata.

Leprosy was not just a poor man’s disease and some of the residents at

Culion came from families who could afford to provide a higher standard of

living for their segregated kin. See

below three lovely ladies dressed in their finery on a Saturday night.

Of course, as desirable as these

women were in the early years before a cure was perfected, the medical

community and the Culion Island Administration tried to forbid the

intermingling of the sexes and prohibited marriages among the patients. As time went on, these restrictions were

relaxed and, starting in the 1950’s marriages were sanctioned by the governing

bodies. However, healthy children born

to married patient couples were immediately separated from their parents and

brought to the Sanitarium Nursery – an especially heart-wrenching mandate which

was not over-ruled until the early 1970’s.

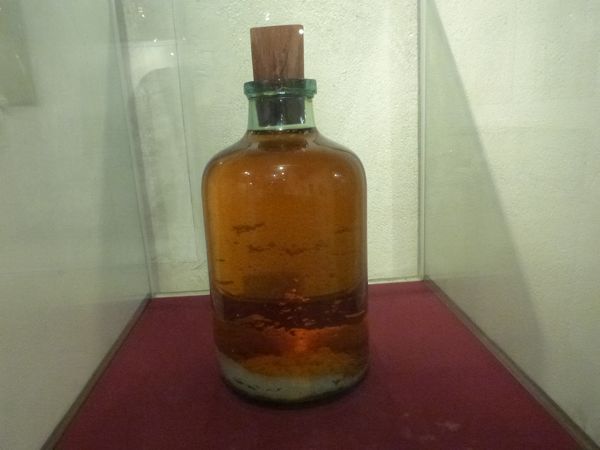

All during this time, research

continued on Culion and experimentation with the use of the oil of the

Chaulmoogra Tree from India - using an injection method developed by Culion’s

Dr. Eliodoro Mercado - proved highly effective and successful.

Later studies at Culion revealed a

cocktail of drugs that would prove highly effective in reversing the effects of

the disease. After almost a century of

research and experimentation, the medical staff at Culion could claim responsibility

for many major medical breakthroughs in the fight against leprosy and, at

least, in the case of Culion Island itself, total eradication of the disease by

1998.

The last patient was successfully

treated and released from the Culion Sanitarium in 1998. That same year, the Culion Town received

municipality status and those patients and their families as well as

descendants from the earliest leprosy victims who had chosen to remain on the

island could now freely mix with the “Sano” residents all over the island.

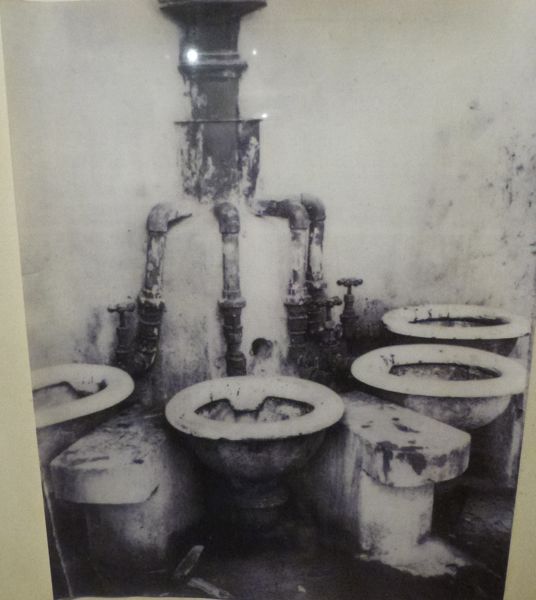

Today, the Leprosarium wing of the

hospital on Culion Island is open to the public as a museum with a magnificent

collection of memorabilia from the first dark days on “the island of the living

dead” to the happier times when it became clear that a cure was possible. Visitors can roam through the Patient Wings

where the images of those first early days are abhorrently clear in the

communal toilets.

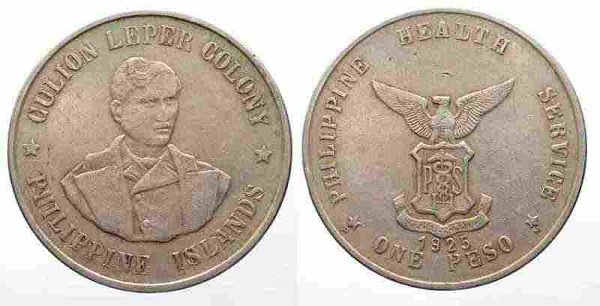

On view are also Currency Notes and

Culion Leper Colony coins that were issued by the Department of Health to avoid

the contamination of legal tender and to assuage the concerns of the general

population. But, one can only imagine

the humiliation it caused the patients.

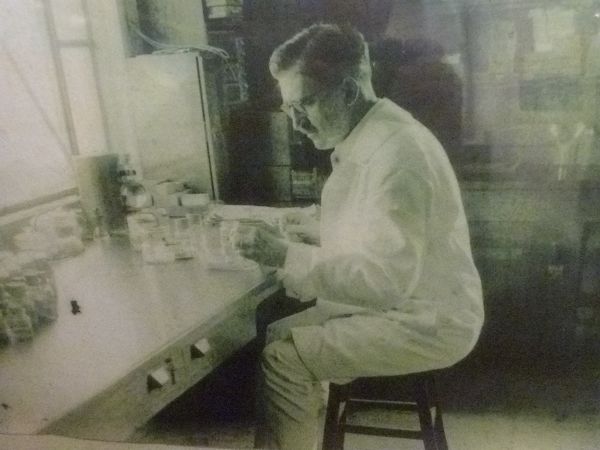

Visitors to the museum can also see

the laboratories and equipment used over the years at Culion as well as a room

filled with blood samples and microscopes documenting every patient who resided

on Culion Island during the 20th Century.

A visitor to Culion Town today sees

a lovely seaside community with historic buildings such as the Inmaculada

Concepcion Church and sparkling vistas from the ramparts around the city

walls.