12:09.43N

68:16.84W

14th April – Initial Impressions of Bonaire

We

knew that the 400NM or so passage from Grenada to Bonaire was likely to take us about two and a half

days. That being the case, it made

sense to leave in the evening to ensure that we got there in daylight 3 days

later. In the event our enthusiasm

overtook us. We needed to refuel

(just in case) and on our intended day of departure, Sunday 9th

April, the fuel berth in Prickly Bay closed at 1400. As soon as we’d refuelled we set off,

knowing that we risked arriving too early and that we’d have to sort that out

later. Our departure was delayed

for a short time – we didn’t actually leave until about 1530 – because the fuel

berth attendant and all of us were monitoring a Mayday call to see what

assistance we might provide. A

clearly distressed Swiss woman made the call after her husband had been more

than an hour overdue returning from diving (he was diving alone – a no, no) near

an island off the south west tip of Grenada. However, a number of boats in the

area homed in and the diver was found alive and well. The relief in his wife’s voice was

palpable and, quite by coincidence, we got talking to a Swedish couple at the

fuel berth (immaculate English, of course) who knew them well and were arranging

to meet up with them that evening for a group hug.

Westward, ho – after months of heading broadly north or south with

westerly winds within and between the Leeward and Windward

Islands. It was an easy

passage with the wind pretty well dead aft at between 10 and 15 knots, a slight

following sea and a westerly current.

It got a bit rolly at times but nothing compared to the rolls we’d

experienced coming across the Atlantic from the Canaries to St

Lucia.

We poled out the headsail, fitted a preventer to the main boom (to stop

it being a nuisance and gybing on us when it, rather than we, felt like it) and

headed off downhill with Orville the autohelm in charge of steering.

There

are a few Venezuelan islands on the straight line between Grenada and Bonaire so we had to gybe twice

(that’s a gybe almost every day – eat your hearts out, you Solent racing boys and prepare for the competition on our

return). We had toyed with the idea

of visiting a couple of the Venezuelan islands on the way (cruising mainland

Venezuela was, sadly, completely off the agenda - read on) but the formalities are

burdensome now and the entry fees not inexpensive. We had also heard that President Chavez

has directed his government to send deserving Venezuelan public employees on

holiday to these islands and that, for some related reason or other, visiting

yachts are not welcome. Nah, come

on. We can create all the hassle we

need, ourselves, without outside assistance. Thanks. Such a shame – such good tales of when

Venezuela (mainland and all) was a

cruising paradise. It is not the

purpose of this blog to be political.

However, it does occur to us that, in a country with as many natural

resources as Venezuela, if the economy has gone to the dogs and you have,

reportedly, around 20,000 murders (up 20% over the last year, apparently) and

5,000+ kidnappings a year, there may be a case for a brief review of government

policy and departmental operation in one or two areas. Again, reportedly, the message from the

top has been that the populace should make whatever money it can in whatever

manner it might. Sounds like a

scheme from Hell. But, on the

upside, as our American cousins might say, we suppose that a number of Swiss

bank accounts are in ruder health than ever. As we were to discover, there are lots

of Venezuelans doing responsible jobs in Bonaire – can’t think why.

We

settled into a routine of three hours on, three hours off after dark - as ever a

bit of a shock to the system to start with. Keeping awake initially was a challenge,

particularly as there was virtually no traffic to be tracked. Having left Grenada and until we got within spitting distance

of Bonaire we saw only 2 vessels. Carol did get a bit concerned at one

point – she spotted the tiny (but, conspic) Los Hermanos Islands but couldn’t see a

much larger island called La Blanquilla which was very close by to the

west. Was the chart wrong? Was the chart plotter not working? Had her eyesight completely failed? No, none of these – La Blanquilla,

although relatively large in area, is a sand covered coral reef and only about

50 feet high – quite different from all the volcanic islands we’ve been used to

(she should have listened more carefully to Don Street’s advice in Las Palmas;

“I may not know where the rocks are but I sure know where they ain’t.” –

Ed).

Having

left too early, we arrived correspondingly early having averaged about 6.5 knots

all the way. Anchoring is streng

verboten anywhere off Bonaire and you either go into one of the marinas in and

around the capital, Kralendijk (only one of which could accommodate our draught

and would have cost us $50US+ a night and is a mile out of town- predictably

virtually empty when Jon visited later) or you pick up a mooring off Kralendijk

for $10US a night. Either way, this

is not sensible to attempt at night on your first visit (no marina staff after

about 1700 and the moorings are merely small pick up buoys attached to big lumps

of concrete on the sea bed – no actual mooring buoys at all). So, in the early hours of Thursday

12th, we dropped the mainsail and proceeded under much reduced

foresail, trying hard to trim it sufficiently appallingly that we made around 3

knots. As dawn broke we picked up

an unoccupied mooring and retired to bed until we could go ashore and complete

the formalities.

The latter, it has to be said, are something of a pain. Having rung the marina (which also

controls the moorings) in advance we were told to come alongside the fuel berth

and sort out payment before going to a mooring. When we pointed out that we’d be

arriving significantly before they opened at 0800, we were told to pick up a

mooring temporarily, then take the yacht to the fuel berth to sort out the

mooring fees and then go and pick up the mooring again (what are you talking

about – that’s what we’ve got a dinghy for). Anyway, that wouldn’t have worked

because the first thing you have to do anywhere around here is clear in through

customs and immigration. And they

are located on the sea front but about a mile south of the marina. So, feeling somewhat bolshie now, we

arose when it pleased us and dawdled through breakfast before Jon dinghied

ashore to try to find the customs office.

This was apparently easily identified (according to the pilot book) as

being the only turquoise building on the seafront. It isn’t turquoise any more. Carol is battling for a female

description of the colour (sand, ochre, apricot . . .). It’s dull yellow, believe me. But, hey, it wasn’t that difficult to

find. The office appeared to be

very crowded but it became apparent that only one yacht was being

processed. For some reason the whole of the yacht’s crew were sitting

like dummies watching the fascinating process of a skipper filling in two forms

asking for the same information in two different formats. Jon got hold of the necessary forms and,

once the previous crew had cleared out, presented his for inspection together

with the passports for Carol and himself.

He was immediately despatched back to the boat to collect Carol because,

uniquely in our experience so far, Bonaire

immigration requires to see flesh and blood as well as the passport to which it

relates – on both check-in and check-out.

Presumably the same would be true in Curacao if you checked in or out there. A mile hike to the marina followed to

sort out the mooring fees. That was

a mistake – really should have taken the dinghy – identifying the marina office

from the road is practically impossible – so a lot of wombling around was

required. From the fuel berth it’s

dead easy. Anyway, by now it’s

midday. That means no action until

at least 1330 – although, helpfully, the sign on the door (one of those “Sorry

we’re closed; back at . . .” whatever time shown on clock face) indicates no

action until 0900 the next day.

It’s a lot of effort to move those hands, y’know , twice a day,

particularly if you’ve only got a bare hour and a half for lunch.

Chris

Doyle’s guide alludes to the fact that Bonaire is sometimes criticised for not

being yottie friendly – much more into cruise ships and the wads of cash their

passengers find it burdensome to continue to carry around. So, he mounts a somewhat philosophical

rebuttal of that assertion and assures us that we’re all special in the hearts

of the locals. All I’d say is that

if you want yotties to come and you arrange that most of them will have to take

a mooring, that is absolutely no problem.

Just provide some dinghy docks so they can get ashore. It’s not complicated. There is no beach here so you need

a dock to get ashore. Coral runs

out from the shore for a few metres and then down, down, down we go. The choices for getting ashore by dinghy

are:

The afore-mentioned marina – a mile out of town

Karel’s Bar – around about town centre - a badly set up and small

capacity dock which is difficult to clamber up and down and where we wouldn’t

dream of leaving a dinghy for long.

The Nautico Marine dock – around about town centre. This is a small yacht dock equipped with

‘dolphins’ and is capable of taking a few yachts provided your draught isn’t

anything very great. Not a starter for Arnamentia. Entry to the dock is via a locked gate

and you need to get ashore at the right time to get hold of the bloke who runs

it to pay him $10US for the key needed to let you use it to bring your dinghy in

and out for a week or part thereof.

The right time occurs 4 times a day (1000, 1200, 1400 & 1600, just

before he drives his water taxi to Klein Bonaire and back again). Once you’ve done that, you’re home and

dry – apart from the fact that you’ll need to remember to reclaim your $20 key

deposit before you leave.

C’mon,

guys, sort yourselves out.

The good ship Deutschland – complete with a towel for every

deck chair

Bonaire is an autonomous island

federated to The Netherlands and one can see that the early Dutch settlers must

have felt at home here. The

majority of the island is very flat, though the hills at the north end are

probably higher than anything back in Holland.

The southern part floods partially in the rainy season but the

inhabitants have resisted the temptation to build dykes – possibly because

they’d sussed that that wouldn’t work – what with the problem water being

delivered vertically rather than horizontally. The south is also much taken up with

salt pans and their product is a substantial contributor to the island’s

economy. Klein Bonaire, the

small uninhabited island opposite Kralendijk, looks just like a section of the

Dutch North Sea coast – low lying sand dunes and some scrub. The diving and snorkelling here is

reputed to be world class and we are looking forward to doing both. More of which anon.

Kralendijk waterfront from Arnamentia’s bow

Incidentally, the Dutch regard the Dutch Antilles (Aruba, Bonaire,

Curacao (ABCs)) as the Leeward Islands whilst their other islands, Sint Maarten,

Saba and Statia (part of what the British would regard as the Leeward Islands)

are, to them, the Windward Islands. All depends on your point of view. For the British in the 18th

Century or so, getting to the Lesser Antilles islands from their N American

possessions (before the Americans decided – unaccountably and perhaps a little

presumptuously - that they could manage their own affairs better than the

English monarch) involved a beat to windward and the more southerly the

destination the longer the beat.

So; Martinique and everything south became the Windward Islands,

Dominica and everything north

became the Leeward Islands. For the Dutch, the ABCs were

significantly to leeward of their other Caribbean possessions. So, the logic was reversed.

A first sight the town of Kralendijk is not lacking in charm. There is quite a lot of colonial Dutch

architecture and things are pretty well organised – if occasionally a bit

ponderously so. Inevitably there is

a flashy mall to cater for the demands of the cruise ships for duty free

bling. But, there is little of the

vibrant soul, fizz and delightful chaos and colour you encounter in the

Windward Islands. No blaring music, no hustling busses and

taxis, no strident calls for your attention in the markets, no hyper-active boat

boys vying for your trade in almost anything, few locals either manically

grinning, screaming with laughter or singing at the tops of their voices, no

dreadlocks. It’s all rather

restrained and such food as we have sampled so far is unremarkable – gasthaus

dull. Moreover, here we are at

Saturday lunchtime and most of the restaurants and bars closed at midday. Sorry; non comprendi.

An

eclectic mix of architecture ……………….

Austrian chalet and Dutch Colonial Cruise Ship Mall

New England Candy

Stripe

Dutch East Indies

Modernist, but not too brutal

And

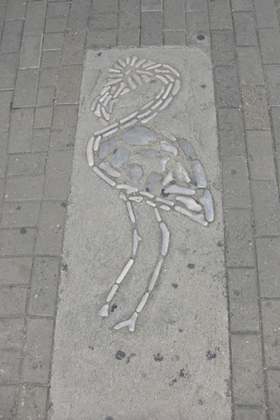

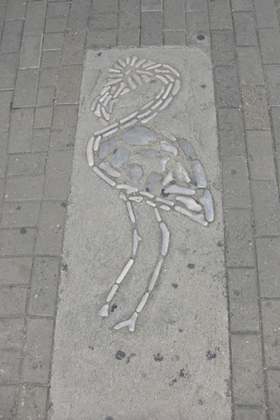

finally, a fun flourish – flamingos adorn the pavements …..

The official language is Dutch whilst the local language is

Papiamento – a Spanish-based Creole which incorporates bits of the language of

every country that has been involved in the island’s history. So, we have a mix of Spanish, Dutch,

French, Portuguese, South African and a bit of English thrown in for good

measure. Fortunately, you’ll get by

more than adequately in English.

There are a great number of South Americans of all nationalities here –

scarcely surprising but one is quite clear that, having sailed away from the

Windward Islands in the Caribbean, you are in

quite different territory here.

We’re

here for a few days and will, doubtless, find out and experience more

yet.