Staying the Course

Vega

Hugh and Annie

Tue 12 Sep 2017 06:04

We are rediscovering the joy of our staysail. This is hanked to an inner forestry and was intended to be a more manageable upwind sail than the original 150% genoa. Which it proved to be, enabling the boat to point higher into the wind than the genoa whilst being much easier to tack. Since we have had the smaller genoa with two reefs built into it we have had little need for the staysail. However, with the recent strong wind I hanked on the staysail as a downwind option and keep it in a sailbag made for the purpose on the foredeck. We now find that when running downwind a combination of genoa and poled out staysail easier to set up and manage than poled out genoa and mainsail with a preventer. The staysail is large enough to make a knot of additional speed but small enough that it can be left up in strong wind whilst reefing the genoa. So, in up to 20kts of wind we now put up full genoa and staysail. If the wind increases above 20kts we can easily reef the genoa and with two reefs the genoa is the same size as the staysail making a perfectly balanced combination for strong wind and at night.

We have just spent a week on a mooring at Palmerston island. A week because we were waiting for a big high pressure system to pass through with associated strong wind. The islanders maintain 10 moorings for visiting yachts but their upkeep is with the support of the yachties who provide line, shackles and so on and also underwater maintenance when scuba gear is on board. Our mooring chain appeared to be in reasonable condition underwater but the end with the line and loop for running the attaching lines through from the boat was looking the worse for wear. We made a second loop as a failsafe using one of our mooring lines but nevertheless I spent each night sleeping fitfully and anxiously in the saloon next to the depth alarm as the wind rose to a peak at midnight before lessening towards dawn. The mooring chains are tied to the coral on the narrow shelf on the outside of the reef - there isn't a deep enough passage to get a yacht into the lagoon. In front of us the seabed rose rapidly from 20m directly beneath up to the reef. Behind, the shelf dived down into the abyss. A westerly wind or big swell can swing you onto the reef and there are the remains of a yacht ashore to remind you of this. We were advised to lower our anchor to within a metre of the seabed so that if the boat did swing the anchor would hold us off the reef. The difficulty with this was that when the boat swung even a small amount the anchor was dragged across the coral and the grinding reverberated through the boat. Raising the anchor to 10m was the only way to prevent this. We set the depth alarm to 10m and on the bigger swings this would go off just keep us on our toes. When we went ashore we left the AIS on so that if Vega did break free at least we could have the pleasure of following her progress across the Pacific.

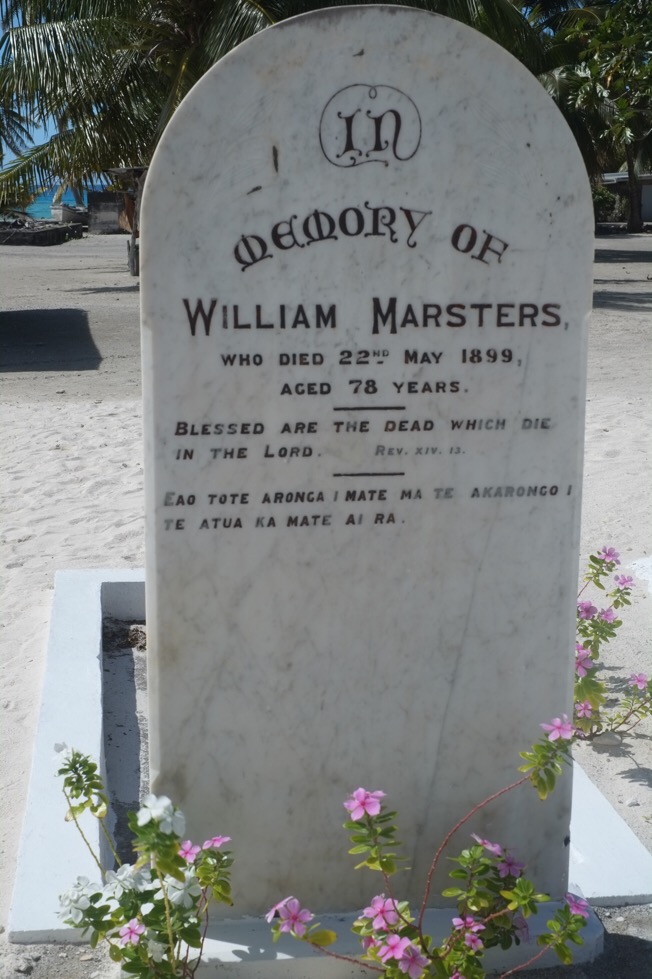

Palmerston is fascinating for two reasons. Firstly the island is occupied by three families, all directly or indirectly descended from William Masters who settled there with three Polynesian wives in 1862. One of the three families will adopt you for your stay, running you to and from your yacht each day and giving you lunch. In return you gift whatever might be needed in the way of equipment or expertise or what would be considered a luxury on the island. Ideally you contact the island in advance and you may be requested to buy something on their behalf in say Tahiti or Rarotonga. The 51 islanders cherish their isolation but at the same time are well supported by the Cook Islands government and New Zealand. They have a school and also state of the art solar power station grant funded by a joint NZ and Australian development fund. Another reminder that to live comfortably in splendid isolation you also need the infrastructure provided by more developed and industrial economies.

Secondly Palmerston has a regular visiting colony of humpback whales that come up from the Antarctic to breed. A mother and calf swam right by the boat not long after we arrived at the mooring. Thereafter we kept looking but they usually appeared while our backs were turned and we would be asked if we had seen the whales right by our boat. One night they were singing so loudly we thought they must be right underneath us. Wonderful but a bit disconcerting.

Our mooring did survive the week of winds with us clinging on and after Palmerston we set off for Beverage Reef. Beveridge is a mostly submerged reef surrounding a shallow lagoon about two miles across. It is very bizarre being at anchor in only 10m of water in what appears to be the middle of the Pacific. Getting in there involved following waypoints on the plotter for the pass through the reef and with big standing waves and poor light at the end of the afternoon never had we been more reliant upon electronic aid nor more relieved when we made it into the lagoon. Once in the lagoon there was a stark reminder of how electronic navigation charts cannot be relied upon implicitly. The catamaran Avanti had sailed onto the reef a few nights previously without realising it was there. Sometimes small features will only show on the chart when you zoom in and apparently Avanti, while following the direct route between Rarotonga and Niue, had the chart plotter set to a small scale on which they could see Niue but not the reef. It made the national press back in the UK. Aware of this issue Annie, when passage planning, scans the route at large scale and marks anything we should be aware of such as reefs. It is yet another reminder of how you cannot take anything for granted and how small mistakes can have catastrophic consequences.

The family on Avanti was incredibly lucky that there happened to be a big New Zealand research yacht at anchor in the lagoon (and which is now next to us in Niue) that could take them off in the morning and then pull Avanti into the lagoon where she lies at anchor, listing and slowly sinking.