Journey to the Roof of Australia

VulcanSpirit

Richard & Alison Brunstrom

Fri 28 Nov 2014 02:17

|

Your intrepid correspondents, together with Australian family have been off

down south, to Konquer Kozzie (my best attempt at Oz-speak) - more formally

Mount Kosciuszko, Australia’s highest mountain at 2228m (c 7000ft). The

mountain is best reached by chairlift to the plateau, then a very easy almost

flat 6km hike along a metal track.

Here is some of the team exiting the chairlift. This is quite exciting the

first time as the safety bar won’t lift up leaving you trapped in the chair and

about to go straight back down whence you came. You then discover that you have

your feet on the footrests connected to the safety bar so it can’t raise. By the

time you have worked all this out (2 secs) you have to move very smartly to get

clear. Here are some Australians caught in the act:

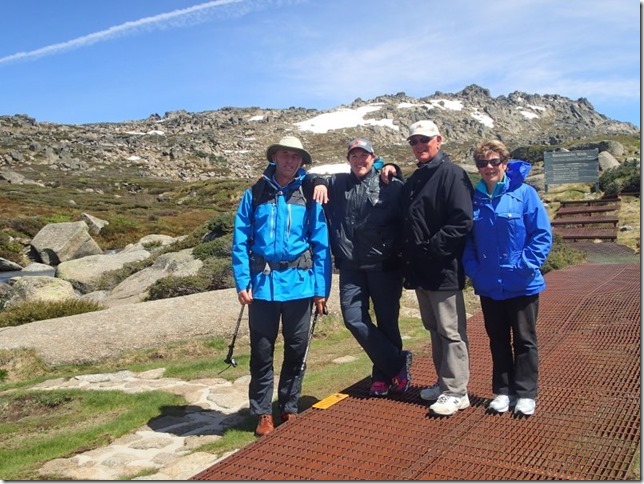

From left to right sister-in-law Donna Brunstrom, her mother Helen and

father Gary. And here is the group enjoying a well-earned cuppa in the chairlift

cafe, frozen half to death, with the alpine village of Thredbo seen through the

window:

L to R: Me, Donna, Helen, Gary.

The track to the summit is mostly a metal grill to protect the very fragile

montane vegetation:

The previous day had seen 75mm of rain after weeks of beautiful weather;

our day started sunny but freezing cold so both sun protection and lots of warm

clothing was the dress of the day. We met a surprising number of Swiss visitors

complaining about the cold. Close observation of the picture will reveal my

walking trousers, derided by the female half of the VS crew as being humorously

short, and my sensible new brown walking shoes derided by my sister-in-law as

“something that (my brother) Alan would wear”. It’s just water on a duck’s

back.

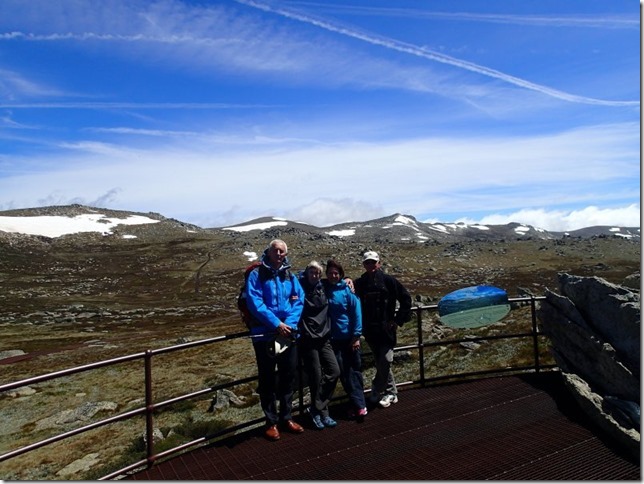

Mount K lookout: me, Ali, Donna, Gary, with Kosciuszko over my head:

A typical plateau view, of Lake Cootapatamba, one of only five glacial

lakes in Australia.

And here is Ali on the summit, with the weather closing in:

Why is it called Kosciuszko, you might well be asking. I think the answer

is really fascinating. The mountain was named on 12 March 1840 by a Polish

explorer geologist and surveyor (he carried his survey instruments right up onto

the plateau to be sure of finding the highest peak), PawelStrzelecki. He may

literally have been the first human on the top as white settlers had only

recently arrived in the valleys below and the Aborigines had regarded the tops

as sacred places for spirits only. He named is Kosciusko because he thought it

resembled the tomb in Krakow of one of his heroes, General Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

Kosciuszko was a remarkable man who never set foot in Australia but was

well known internationally for fighting for the values of freedom, liberty, and

equality of all races. This led him, via Polish Military College and Paris where

he specialised in military engineering under Vauban, to fight for the Americans

during their War of Independence. He rose to Brigadier General and played an

absolutely crucial role in the Battle of Saratoga, regarded as the turning point

in the war. He designed and built the fortress of West Point, which was regarded

by the British as impregnable (so it was never attacked). This secured the

Hudson pathway and forced the British to turn away and move south to their

eventual capitulation at Yorktown. Kosciuszko returned to Poland, fought

unsuccessfully for Polish freedom from the Russians and died in 1817. Having

failed to persuade the American Founding Fathers to end slavery he left much of

his American estate to Thomas Jefferson for the purpose of purchasing the

freedom of slaves and their subsequent education. Seven years after his death a

school for former slaves was established under his name in Newark NJ.

Strzelecki travelled widely in Australia from 1839 to 1843, covering

12000km on foot without any violent encounters with Aborigines because of his

insistence in treating them properly on their own terms. He discovered many

valuable mineral deposits including coal and gold and made very useful maps. He

then settled in England. His seminal “Physical Description of New South Wales

and Van Diemen’s Land”, published in 1845 was described as an asset in

scientific literature for over a century thereafter. He then got involved in

humanitarian work in Ireland during the potato famine, ending up being put in

charge of the relief effort for the whole of Ireland. He is credited with saving

the lives of up to 200 000 children. Queen Victoria knighted him Sir Paul

Strzelecki in consequence.

|