Gandhi's Early Life

|

Mohandas Karamchand

Gandhi's

Early Life

Gandhi’s

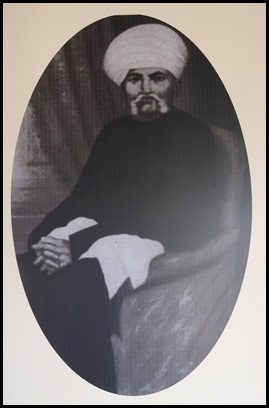

parents were Karanchand Uttamchand Gandhi and Putli

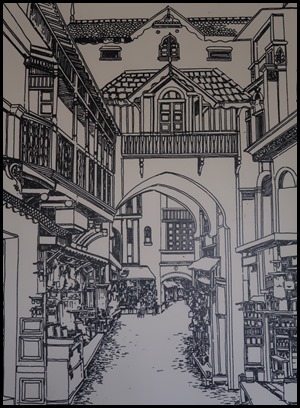

Bai. Manik Chowk, Porbandar.

The Gandhi’s, for generations, had been grocers. Uttamchand Gandhi. the family patriarch somehow managed to procure the job of Deewan, that is, a minister in the state of Porbandar. His son Karamchand Gandhi followed in his footsteps. Although he only had an elementary education and had previously been a clerk in the state administration, Karamchand proved a capable chief minister. During his tenure, Karamchand married four times. His first two wives died young, after each had given birth to a daughter, and his third marriage was childless. In 1857, Karamchand sought his third wife's permission to remarry; that year, he married Putli Bai (1844–1891), who also came from Junagadh, and was from a Pranami Vaishnava family. Karamchand and Putli Bai had three children over the ensuing decade: a son, Laxmidas (1860–1914); a daughter, Raliatbehn (1862–1960); and another son, Karsandas (1866–1913).

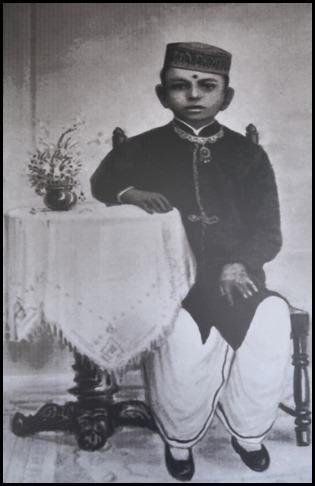

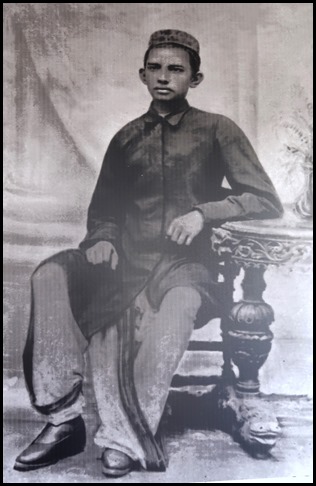

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

aged seven and about

fourteen.

On the 2nd of

October 1869, Putli Bai gave birth to her last child, Mohandas, in a dark,

windowless ground-floor room of the Gandhi family residence in Porbandar city.

As a child, Gandhi was described by his sister Raliyat as "restless as mercury,

either playing or roaming about. One of his favourite pastimes was twisting

dogs' ears."

There was nothing extraordinary about his upbringing. He must

have been around seven when the family moved to Raijkot and he was admitted to

the local primary school. Like his schooling in Porbandar, there was hardly

anything to note about his early schooling. A shy Mohan would be at school and

at the stroke of the bell he would run back home as soon as school

finished.

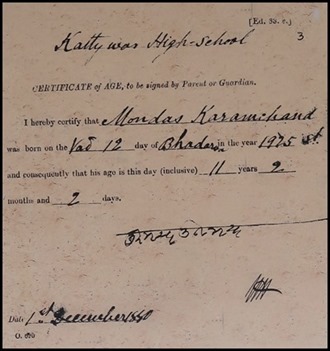

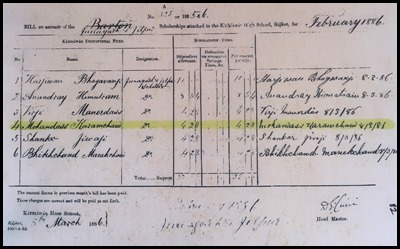

Mohan’s certificate of age and his Scholarship Roll of Kathiawar High School,

Rajkot.

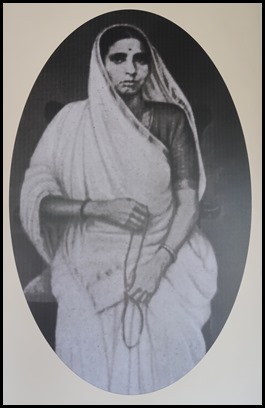

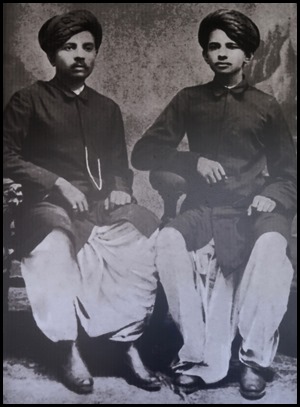

Kasturbai Makhanji Kapadia. Kasturba was born the daughter of Gokuladas Kapadia and Vrajkunwerba Kapadia. The family belonged to the Modh Bania caste of Gujurati tradesmen and were based in the coastal town of Porbandar. Little is known of Kasturba's early life. In May 1883, 14-year old Kasturba was married to 13-year old Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in a marriage arranged by their parents, in the traditional Indian manner. They were married for a total of sixty-two years. Recalling the day of their marriage, her husband once said, "As we didn't know much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives." However, as was prevailing tradition, the adolescent bride was to spend the first few years of marriage (until old enough to cohabit with her husband) at her parents' house, and away from her husband. Writing many years later, Mohandas described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride, "even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me." At the beginning of their marriage, Gandhi was also possessive and manipulative; he wanted the ideal wife who would follow his command. Kasturba and Gandhi had five sons, with their eldest dying shortly after birth. Although their other four sons (Harilal (1888 – 1948), Manilal (1892 – 1956), Ramdas (1897 – 1969) and Devdas (1900 – 1957) survived to adulthood, Kasturba never fully recovered from the death of her first child. The first two sons were born before Gandhi first went abroad. When he left to study in London in 1888, she remained in India. In 1896 she and their two sons went to live with him in South Africa.    Mohan and brother Laxmidas, 1886. Later –

sister Raliyat Behn and Laxmidas.

A chance meeting with an old family friend

opened up the option of going to England to read law. Already anxious about

going to college, Mohan jumped at the proposal.

The decision was unprecedented in the clan. The entire modh

baniya community stood in opposition. A resolution cancelling Gandhi’s

expulsion from caste and readmission was passed. The family was apprehensive as

well. How would a young man stay true to his beliefs in a faraway land ? Mohan

vowed to his mother not to touch wine, women or meat. This done, he obtained his

mother’s permission, and set sail for England on the 4th of September 1888 from

the Port of Bombay.

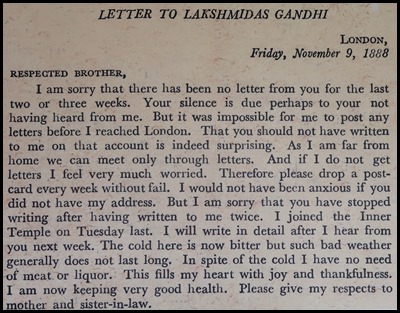

Letter to brother, Laxmidas and an Application for Scholarship sent from

London.

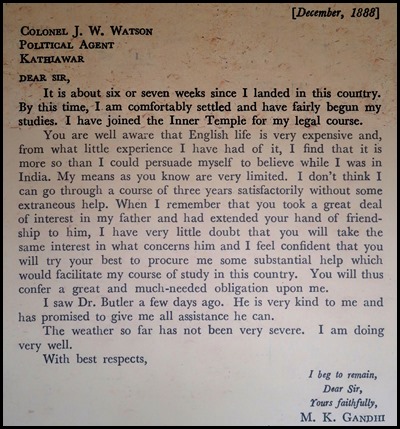

Gandhi with members of The London

Vegetarian Society, London.

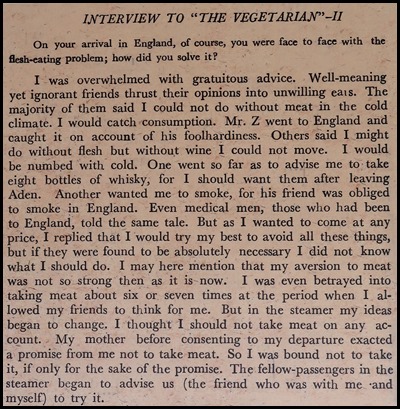

During his stay in London, Gandhi analysed vegetarianism afresh. He

associated himself with The London Vegetarian Society

and became its executive member. He propagated vegetarian lifestyle and even

designed the logo of the society.

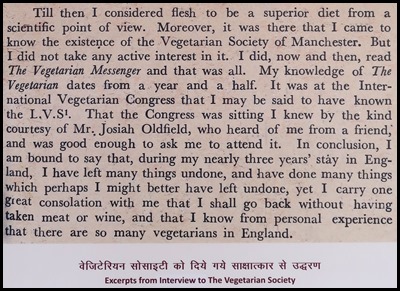

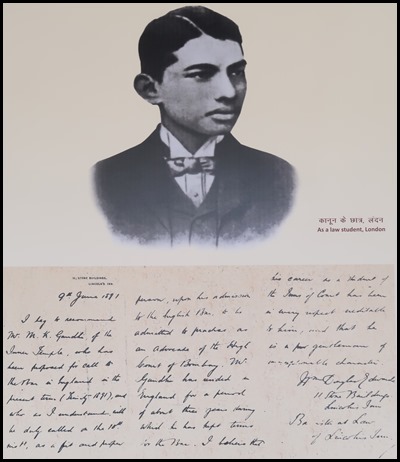

Letter of recommendation from Mr. D.

Edwards and Bar-at-Law

Certificate.

In addition to becoming a barrister in England, Gandhi got

into the practice of living an austere life in an alluring world, vegetarianism

got a new meaning. He also got exposed to various other religions.

July 1891, return to India. But he had still not ‘learnt’ to

be an advocate. Even when he got a case or two, he would not pay the requisite

commission. In the

meantime a Meman firm from Porbandar approached his brother. The firm needed an

advocate to handle its cases for a year in South Africa. Barrister Gandhi

accepted the offer and left for Natal.

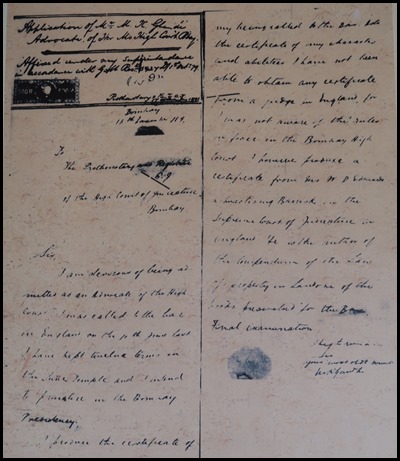

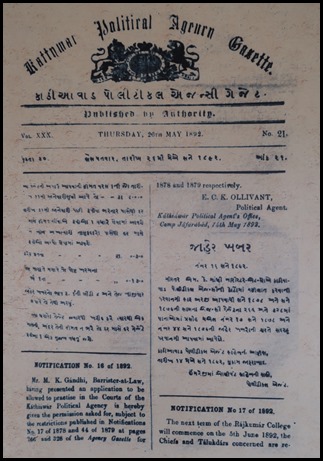

Application for

admission as an Advocate to the Bombay High Court. Gazette announcement permitting Gandhi to practise in the

Courts of Kathiawad.

Africa 1893 – 1914.

Satyagraha (a policy of passive political

resistance) in South Africa. South Africa,

like India was a colony of the British Empire. Apartheid – the horrific system

of racial segregation – was widespread. Within a few days of his arrival in May

1893 at Durban, Barrister Gandhi realised that he was only a ‘cooloie barrister’

in this land. The Indian labourers brought here to work were made to enter into

a five year agreement with the Government. The word agreement got corrupted into

‘Girmit’ and persons with such Girmits became ‘Girmityas’. The colonisers called

them ‘coolies’.

Barrister Gandhi had to travel to

Pretoria for a hearing by train. He booked into a first class apartment for the

overnight journey. On his arrival at Maritzburg around nine in the evening, he

was told to move to a lower class. His refusal to comply had him thrown off the

train.

Gandhi saw this personal

humiliation as only a symptom of the deep disease of Apartheid. Soon several

other symptoms of this disease started becoming visible to him. And then came

the notification requiring every Indian, adult and child to sign up for the

latest agreement. Apart from very detailed information, it required them to

provide fingerprints. Non-compliance with this would result in

deportation.

From these circumstances emerged

the widespread movement based on non-violence and insistence on

truth.

The satyagrahis ultimately

succeeded in this trial by fire. With non-violence but firm weapon of

satyagrapha they not just encountered hatred but also through a process of

self-purification.

The Indian Opinion was a weekly

newspaper launched by Gandhi to fight racial discrimination and win civil rights

for the Indian immigrant community in South Africa. Its first issue was

published on the 4th of June 1903 in English, Gujarati, Hindi and Tamil and

became an important tool for the political movement led by him and the Natal

Indian Congress. These languages were selected by Gandhi in view of the Indian

immigrants facing the racial discrimination.

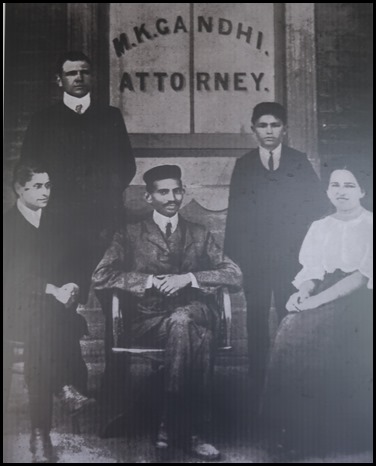

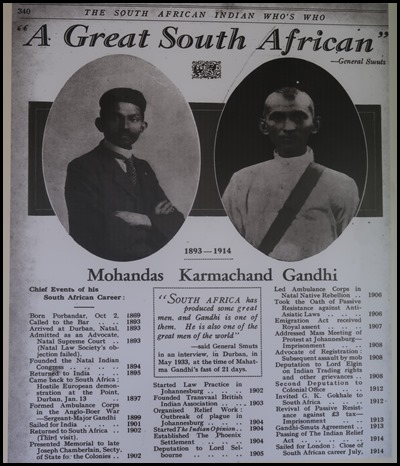

Gandhi in front of

his office with his secretary, Miss Schlesin and Mr. H.S. Polak in

Johannesburg. Chronology of Gandhi’s chief events in South

Africa.

Mohandas went to

South Africa for work. But gradually he realised that he has to fight for the

immoral practices of racial segregation towards the Indians residing there. The

office for legal practise opened by him with so much enthusiasm was gradually

closed and was replaced by the social service. The barrister Mohan who was

treated like a coolie got the recognition as a Great South

African.

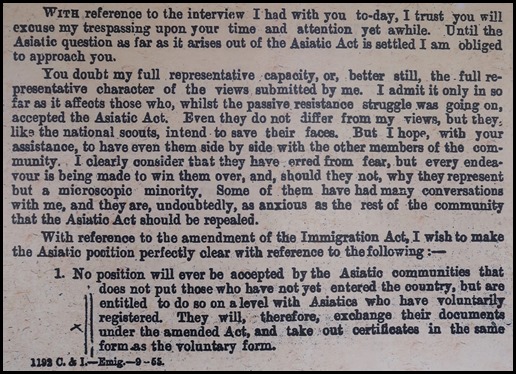

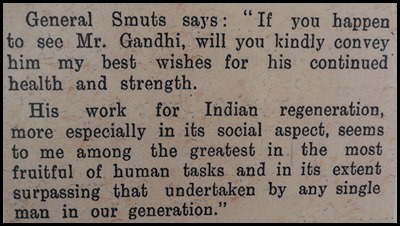

Many atrocities and

exploitations. The conditions of Asians sometimes appeared improved and

sometimes complicated. In February 1908, there was some compromise with General

Smuts who was considered a most brutal Administrator but towards August, the

agreement was broken. Around 3,000 people gathered in a mosque in Transvaal,

which was filled to the brim. All of them burned their certificates en

masse.

January 1908. Mohandas went to

jail for the first time: Compromise was made. He was released. But the

atrocities of the Britishers did not lessen. New problems occured daily. The

Government even declared the traditional marriages illegal.

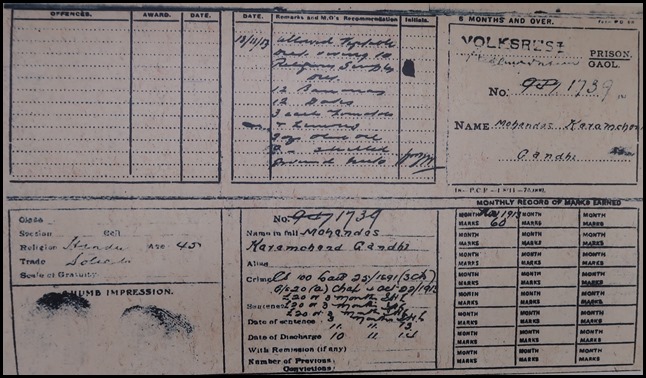

The preparations were made for a

grand march. Apart from Girmitiyas, labourers working in the mines along with a

large number of women joined the march. Gandhi was arrested and was kept in the

Volksrust Jail along with his friends Shri Kallenbach and Shri Polak. His prison number was 1739.

During his twenty-one years in South Africa, Gandhi was sentenced to four terms of imprisonment, the first, on the 10th of January 1908 to two months, the second, on the 7th of October 1908 to three months, the third, on the 25th of February, also to three months, and the fourth, on the 11th of November 1913 to nine months hard labour. He actually served seven months and ten days of those sentences. On two occasions, the first and the last, he was released within weeks because the Government of the day, represented by General Smuts, rather than face satyagraha and the international opprobrium it was bringing the regime, offered to settle the problems through negotiation. Gandhi described his apprehension on being first convicted: "Was I to be specially treated as a political prisoner? Was I to be separated from my fellow prisoners?" he soliloquised. He was facing imprisonment in a British Colony in 1908, and he still, at the time, harboured a residue of belief in British justice.

Gandhi to General Smuts on the 13th of June 1908.

India 1915 – 1947.

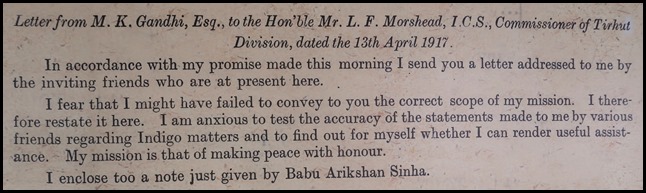

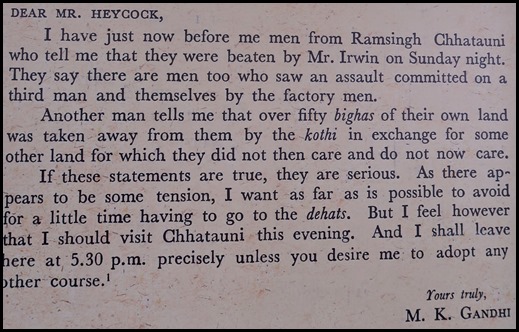

Gandhi’s letter to Mr W.B. Heycock from Motihari, 25th of May 1917.

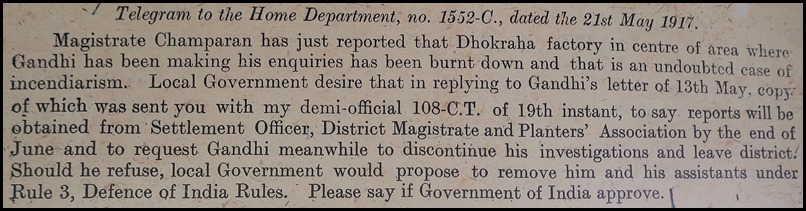

The earliest glimpses of the exploitation of farmers engaged in indigo plantations is recorded by an English official himself. Writing in 1848, Deputy Magistrate E.D. Latur of the Bengal Civil Service observed that every single indigo bale reaching the English shores was drenched with human blood, which could never be wiped off. Shri Rajkumar Shuki, and indigo farmer from Champaran, met Gandhi and convinced him to visit Champaran. Gandhi arrived in Champaran in the second week of April 1917. Entries in Shuki’s diaries for April and May show how closely he assisted Gandhi during his visit, arranging meetings for him with local leaders, accompanying him to court, making provisions for his travel and stay. Initially Gandhi agreed to go for a couple of days, but he stayed on for as long as it took to permanently end the grave exploitation. The resistance based on truth and non-violence gave a new strength to the opposed. The British officialdom too got their first taste of Satyagrapha, the powerful tool of non-cooperation that was in-the-making, and were at a loss to fathom how to counter it.

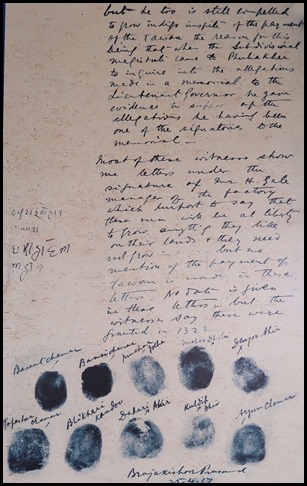

Partition of Ryots (peasants) with thumb prints.

The district administration ordered Gandhi to leave Champaran. His refusal to abide by the order resulted in a summon by the local court. A huge mob gathered at the Motihari court to catch a glimpse of this fearless mortal. Gandhi not only accepted all charges but also asked for an appropriate punishment. The court would have never seen such a spectacle. Gandhi proceeded to lodge the complaints of thousands of poor peasants. With the help of fellows, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Brijkishore Babu, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, J.B. Kriplani, Gandhi had filed complaints of thousands of peasants. Full precautions were taken while filing the complaints so that only facts were recorded. “No drop of poison should be mingled in the ambrosia”. Although the enquiry spearheaded by Gandhi was still in progress, the Bihar Government sen a letter to stop the enquiry and advised him to leave Bihar. Gandhi replied “Enquiry will still go on.....I will not leave Bihar until the problems of people will not come to an end.” Now the Government had only one option that they themselves had to institute an Enquiry Committee and include Gandhi in it. And this is exactly how it happened. The British Government that was determined to throw Gandhi out of Champaran, and put him under trial, was forced not only to withdraw the case but also send its own officers to enquire into the matter. It was through this moral force that Mahatma Gandhi was able to wipe off the stain of indigo. Eventually, Gandhi was able to win significant concessions for the peasants. Gandhi’s first ‘win’ on home soil.

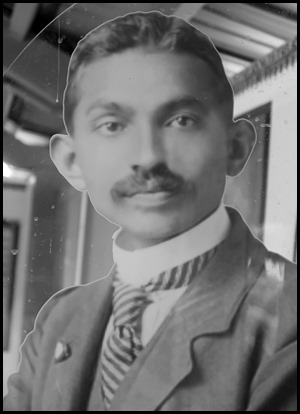

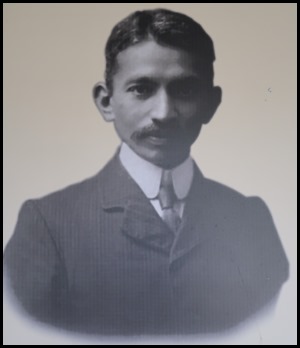

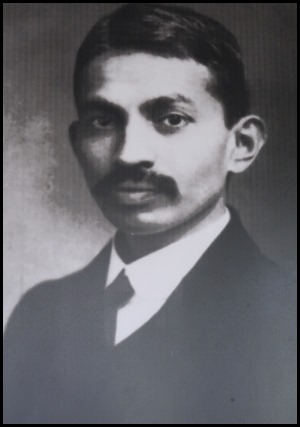

From young barrister to mature man of grit and determination .  General

Smuts

Gandhi spent his life to send out

the message of truth, non-violence and communal harmony, and even gave up his

life for it. His message is relevant more than ever in these times of

intolerance and religious fanaticism.

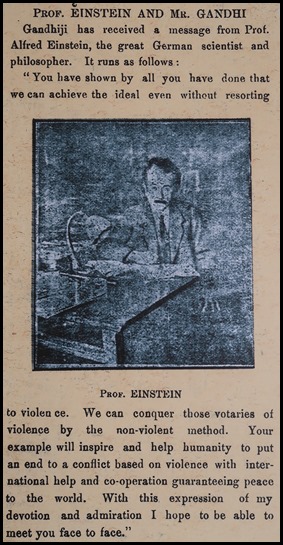

Father of relativity, Einstein had somewhat apprehensively exclaimed that

“generation to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh

and blood walked upon this earth”.

This generation has assured

Einstein that future generations shall never forget Mahatma by declaring his

birth anniversary as the International Day of Non Violence Day. Sadly, the

two never met in person.

ALL IN ALL PLEASED TO LEARN

MORE ABOUT THE MAN

AN AMAZING

STORY |