Shakespeare's New Place

|

Shakespeare's New Place

The final house in the Shakespeare

sequence we visited was New Place, the bard’s home

from 1597 to 1616. In 1616, on William

Shakespeare’s death, New Place house passed to his daughter Susanna Hall, and

then his granddaughter, Elizabeth Hall, who had recently remarried after the

death of her first husband, Thomas Nash, who had owned the house next door.

After Elizabeth died, the house returned to the Clopton

family.

In 1702 John Clopton radically altered, or rebuilt, the original New Place – contemporary illustrations suggest the latter. In 1756 then-owner Reverend Francis Gastrell, having become tired of visitors, attacked and destroyed a mulberry tree in the garden said to have been planted by Shakespeare. In retaliation, the townsfolk destroyed New Place's windows. Gastrell applied for local permission to extend the garden. His application was rejected and his tax was increased, so Gastrell retaliated by demolishing the house in 1759. This greatly outraged the inhabitants and Gastrell was eventually forced to leave town. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust acquired New Place and Nash's House in 1876. Today the site of New Place is accessible through a museum that is housed in the Nash property next door.   In through a gate where the house

used to stand and we were in a pretty garden that

gave us a idea of the footprint of the original house. To our left is the house that was owned by Thomas Nash.

A metal

ship and a rather imposing sculpture at the end of

the path.

The formal

garden that was here in Shakespeare time, that would have been to the

rear of New Place.

William Shakespeare bought New

Place in 1597. It was the only home he ever purchased for himself and his family

– his wife Anne and their daughters Susanna and Judith. Shakespeare’s son Hamnet

died aged 11 in 1596, the year before the house was purchased.

It is thought Shakespeare paid

about one hundred and twenty pounds for New Place. At the time, the yearly

income of a Stratford schoolmaster was about twenty pounds. New Place was the largest house in the centre of Stratford-upon-Avon.

Located next to the Guild Chapel, it was an impressive property appropriate to

Shakespeare’s wealth and social standing. Shakespeare owned New Place for nineteen years until his death in

1616. During this time he wrote more than half his plays.

Whilst thou liest warm at home, secure

and safe. The Taming of the Shrew. Act 5, Scene 2.

New Place was built in 1483 by

Hugh Clopton. In 1540 New Place is described as ‘a pretty house of brick and

timber’. Recorded as having ten fireplaces. in 1602 Shakespeare bought one

hundred and seven acres of land in Stratford for three hundred and twenty

pounds. In 1605 Shakespeare pays four hundred and forty pounds for a share in

the Stratford tithes, from which he made about sixty pounds a

year.

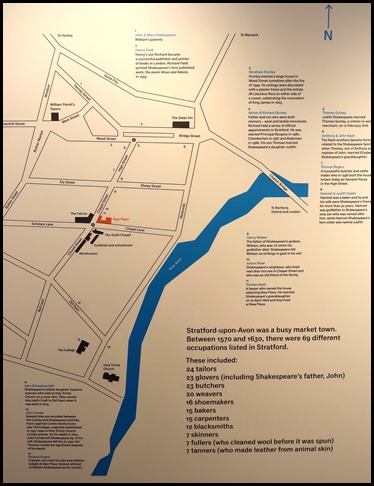

Shakespeare’s

Stratford. Stratford-upon-Avon is where William Shakespeare was born, educated,

lived his early adult life, married and became a father. It is also in Stratford

that Shakespeare makes his financial investments. These included his purchase of

New Place (seen in red on the map), other

houses that he let, and farmland from which he received rental

income.

William’s father, John

Shakespeare, was awarded a coat of arms in 1596. This meant that following his

father’s death Shakespeare could call himself a gentleman. At the time,

Stratford had a population of about 2,500 people but there were only 45

gentlemen in the town. Some had been born into the title, while others were

businessmen who successfully applied for their own coats of

arms.

Four gentlemen in Stratford are

known to have carried a sword as a symbol of their status. Shakespeare may well

have been one of these, as in his will he leaves his sword, an important and

intimate possession, to a close friend.

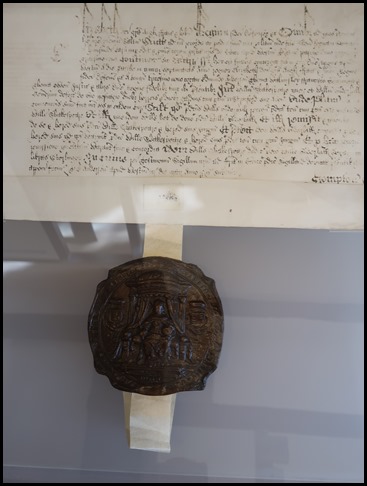

Exemplification of a Fine. An exemplification is

an official copy of a legal action, known as a fine. This one records

Shakespeare’s purchase of New Place from William Underhill. Dated 4 May 1597, it

bears the official seal of the court and was issued in the name of Queen

Elizabeth I.

Shakespeare paid for this copy to

be made to prove his ownership of New Place. He did not pay for the elaborate

initial ‘E’ of Elizabeth’s name to be reproduced.

New

Place was a five-gabled gatehouse with its long gallery on the upper

floor, faced onto Chapel Street. It extended 33 metres (108 feet) from Chapel

Street eastwards along Chapel Lane. The almost central door (seen on the right

of the building) led to a passage dividing the hall on the right from the

service range on the left.

Upstairs we looked up at the

higgledy-piggledy roof and chimneys of Nash House.

Column Capital. A capital is the shaped top of a

column. This one dates from 1702 when New Place was rebuilt by its then owner,

Sir John Clopton. It was recovered from New Place following the demolition of

the building in 1759.

From the upper floor of the

trendy-feeling museum we had not only a better view of the formal garden but

also the large garden beyond. From here we could also

see the theatre, a short walk for WIlliam if he ‘had to go to

work’.

Examples of

clothes that would have been worn by Susanna, Judith, his wife and the

bard himself.

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

Portrait of WIlliam Shakespeare – oil on panel in a

painted wood frame 1610 - 1615. And one man in his time plays many parts.

As You Like It. Act 2 scene 7. William was indeed a man of many parts:-

son, brother, husband, father, grandfather, actor, playwright, shareholder of

the playing company, part-owner of the Globe Theatre, landowner, landlord and

businessman.

Shakespeare was a shareholder in

the playing company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. His name appeared in print for

the first time when his poem Venus and Adonis was published in 1593.

The Globe opened in London in 1599. Shakespeare paid one hundred pounds for a

share in the theatre. Shakespeare and some of his fellow actors were given

scarlet to wear in James I triumphal procession in 1604. In 1613 Shakespeare

bought a gatehouse for one hundred and forty pounds close to the Blackfriars

Theatre in London.

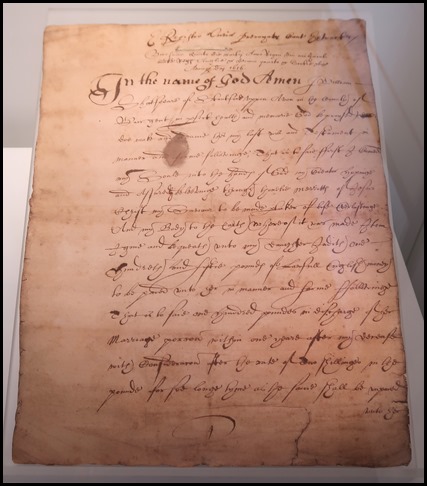

William Shakespeare’s

Will.

This is an

executor’s copy of Shkespeare’s will, made shortly after his death in April

1616. His daughter Susanna and her husband Dr John Hall are named as executors

in the will. This means they were responsible for undertaking – or executing –

his wishes.

William Shakespeare was buried in

a prominent position in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon,

on 25 April 1616. Shakespeare began writing his will in the January of the same

year. The final version, dated 25 March 1616, is preserved in the National

Archives, London and bears his signature. There are a number of amendments to

the document. This suggests that Shakespeare changed his mind about some of the

bequests he had chosen to make to his friends and family. Of the 25 people named

in his will, 21 were connected with his life in Stratford. “called the newe

place wherein I nowe dwell” quote from his will.

To his wife his ‘second best bed

with furniture’ (may not seem much but the second best bed was the marital

bed in those days and seen as quite a romantic gesture (the best bed was

reserved for visitors only use)).

To his daughter, Susanna, New

Place, two houses in Henley Street, all his ‘barnes stables Orchardes gardens

lands tenementes and hereditamentes’.

To his daughter Judith, ‘£150 of

lawful English money’ . She also inherited her father’s silver gilt

bowl.

None of the items mentioned in

Shakespeare’s will are known to survive, but we do have examples of the kinds of

objects he left to his family and friends. 1.Silver gilt

bowl. ‘I gyve & bequeath to my saied Daughter Judith my broad silver

gilt bole’. Silver drinking bowl or standing cup, about 1540. (On loan from the

collection at Charlecote Park).

Sword, ‘to Mr Thomas Combe my

sword’. Combe was a member of a wealthy family in Stratford-upon-Avon and a

close friend of Shakespeare’s. Having inherited his father’s coat of arms,

Shakespeare was entitled to carry a sword in public as a symbol of his

status.

3.

Spoon.‘I gyve & bequeath unto (Elizabeth Hall) All my Plate that I

now have’. Shakespeare’s granddaughter Elizabeth Hall was only eight years old

when he died, but he leaves her all of his ‘plate’, a general term for metal

tableware.

Pewter, with

a hexagonal stem tapering to an end shaped as the head and shoulders of a

monk or priest wearing a hood. About 1500.

Memorial Ring. ‘to buy a ring’. In

his will Shakespeare leaves the sum of 26 shillings and 8 pence to friends,

including fellow actors John Heminges, Richard Burbage and Henry Condell, to buy

rings. rings were a popular Memento

Mori at the time, which means

‘remember (that you have) to die’, and were a way of remembering a dead person

as well as reminding the wearer of their own mortality.

Gold

coins ‘to my godson Willm Walker 20s in gold’. Shakespeare specifies that

the bequest to his godson is ‘in gold’. The coin of the time known as a

‘sovereign’ was a gold coin worth 20 shillings, or one pound.

i Gold sovereign – 1594-6. ii

Gold sovereign 1594-6. Gold half-sovereign 1594-6.

An example of

Shakespeare’s seal. This gold

signet ring bears the initials ‘WS’. One amendment in Shakespeare’s will

suggests he lost his seal ring and could only sign the document: ‘whereof I have

hereunto put my Seale hand’. Could this be Shakespeare’s lost signet ring? It

was found in 1810 near Holy Trinity Church, where his daughter Judith was

married on 10 February 1616, just a few weeks before the will was

finalised.

In the words of

the bard.....

We ducked through the Nash house,

went down the stairs and through the shop, time to

get the Hop On Hop Off back to Anne Hathaway’s House, where we left the car. A

very enjoyable gambol through Shakespeare’s life.

ALL IN ALL LOVELY TO LOOK

BEHIND THE MAN

REALLY INTERESTING

HISTORIES |