Heritage Landing

|

Heritage

Landing

The lower Gordon River is a

narrow estuary within the Tasmanian Wilderness World

Heritage Area. Its geomorphology is in itself of World Heritage

significance. Its beautiful, and delicate, landforms are the legacy of

progressive sedimentary filling of the steep sided river valley after it was

drowned by rising sea levels following the end of the last ice

age.

We arrived at Heritage Landing,

followed the boardwalk and soon found ourselves in a

cool, dense, damp, temperate rainforest, there are few of these left in the

world so not surprisingly this area is very well protected. Around three metres

of rain fall here each year supporting lichen, fungi, ferns and of course the

trees. We enjoyed looking along the way at the rich variety.

Huon pine is a very special, slow

growing tree native to this part of the world. This used to be the oldest in the

rainforest. It may have fallen over – half in 1997, the other three years later,

but new life springs from the old, as soon as a branch touches the floor it

begins to grow roots and off it goes again. It can grow new shoots from

underground each a clone of its parent. Seeds also fall and saplings slowly

begin their long lives.

Huon Pine: It is truly an

ancient species - members of the same plant family (Podocarpaceae) existed more

than 200 million years ago. In Tasmania, the oldest recorded fossils of leafy

Lagarostrobos twigs are more than 2.6 million years old. Growing at just a

millimetre a year, they are one of the slowest growing, longest living trees on

the planet.

Huon pines vary in size from shrubs less than 2 metres high to trees more than 30 metres tall. They grow very slowly, taking about 500 years to reach maturity, and some trees have been known to be more than 3000 years old. In western Tasmania, Huon pine grows in rainforests along riverbanks; it also occurs in swampy flats or lake edges in the state's southern and central regions. It thrives in cool, wet conditions, and is very susceptible to fire. Seed is produced in female cones, with male cones usually growing on separate trees. Huon pine can also reproduce by 'layering', where low-hanging branches touching the soil produce new roots, while still attached to the parent plant. Genetic testing of a stand of male trees on Mount Read on the West Coast has shown that they have been regenerating in this way for more than 10,000 years (although none of the current trees are more than 1500 years old). Huon pine timber has a high oil content and is extremely durable. Early settlers valued it, particularly in the boat-building industry. Its easy accessibility on West Coast rivers was one of the primary reasons for the establishment of the penal settlement at Sarah Island in Macquarie Harbour, in the 1820’s. Curiously, early settlers had been milling Huon pine for decades before the species was given its formal name, Lagarostrobos franklinii, honouring Sir John Franklin, Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania from 1836-1843. Today, Huon pine is a highly valued timber used in small quantities for furniture making as well as boat building.

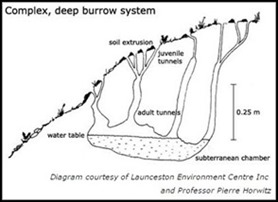

As we bimbled along we kept seeing interesting creature houses, they belong to the burrowing crayfish who dig and live in muddy burrows.

The burrows can be simple and shallow or complex, deep and extensive, and can often be the product of digging activity by several generations of crayfish families. The crayfish build their burrows by rolling little balls of soil to the burrow entrance, building distinctive chimneys that, in sheltered areas, may reach up to 40 cm above ground level. These chaps look like little lobsters and are one of five groups of freshwater crayfish native to Tasmania. They are small with two prominent claws and a general body length under ten centimetres. They vary in colour from orange to reddish brown, grey-blue and purple. During the breeding season (late spring to summer) females carry large orange eggs and recently hatched young under their tail. If they lose a claw they happily regrow their missing appendage but it is often a bit smaller than the original, some have mismatched claw sizes as a natural feature.

Back on board we were treated to locally produced cheeses. Bear loved all of them, I loved the brie, cheddar and white cheese.

Our hostess Amanda took the ‘wheel’ whilst the skipper went for a coffee. Bear settled to a glass of red, I stayed on the fizz and we thoroughly enjoyed watching the world go by.

ALL IN ALL AN INTERESTING BIMBLE IN THE FOREST WELL LAID OUT BOARDWALK WITH LOTS TO SEE |