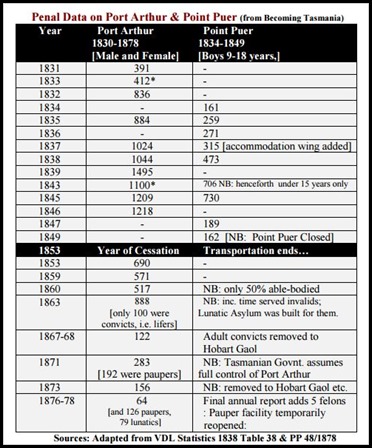

Point Puer

|

Point Puer Juvenile Prison,

1834-1849

After

our visit to the Isle of the Dead, we boarded the ferry once more and our next

stop was Point Puer. We walked up the jetty and in

the freezing wind stood looking at some grass and some trees. We were standing

on an imaginary line, half way across the juvenile facility, where once there

stood a church. The boys that came here were divided - those to the left of the

church had been well behaved on the voyage over, those to the right were deemed

to be troublemakers and ruffians – in for a harsh time. We would walk around the

‘good boys’ end.

A digital presentation of what the site looked like. The

church seen in the middle.

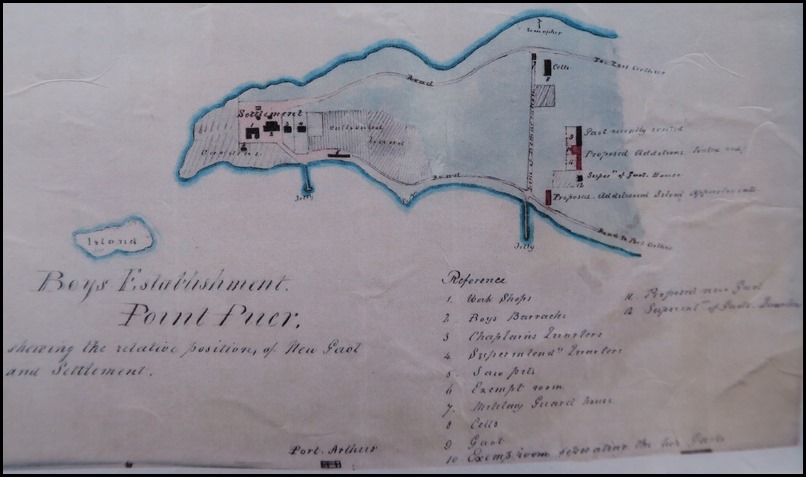

The plan of the site.

When

Port Arthur was established the criminal age of responsibility was only seven.

This meant that children could be thrown into prison with men and women convicts

and, be transported. Child convicts had arrived in New South Wales with the

First Fleet in 1788 and many children were transported to Van Diemen’s Land over

the years. During the convict assignment period (pre-1840) these children were

placed in hiring depots where free settlers could source labour. The settlers

who took their pick of convicts in those depots were only required to feed

them.

The boys, placed alongside adult convicts, were generally overlooked by the settlers as they cost almost the same to sustain but could not do the same work as adults. As a result they remained in the depots causing nothing but a drain on the government coffers. Point Puer (‘puer’ being Latin for youth) was established due to Lieutenant Governor Arthur’s desire to rid the government of this cost, produce more productive young men when they moved into free society and to remove them from the corruptive influence of the hardened adult convicts. The first boy convicts at Port Arthur had arrived around the time it was established. In Thomas James Lempriere’s outstanding book The Penal Settlements of Van Diemen’s Land he writes of two rooms in the Prisoners’ Barracks precinct (one of thirty sleeping berths and the other forty two ) set aside for boys. Arthur initially instructed the Port Commandant, Charles O’Hara Booth, to establish the boy’s prison at Slopen Main on the northwest corner of the Tasman Peninsula, since it still had the buildings remaining from a farm established by Joseph T Gellibrand. Arthur had decided that no free settlers were allowed on the peninsula when the Port was established in case convicts used their bots or supplies to escape. Mindful of the difficulty of administering a station so far from Port Arthur Booth was given permission to build the prison on Point Puer.

Little remains of this prison but it is a very significant site as it was the first exclusively boys’ prison in the British Empire. It preceded the second, at Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight, by some four years. During its fifteen years of operation around three thousand boys passed through it and at the height of its importance in 1842, it was home to around eight hundred youths. The youngest boy at Point Puer was believed to have been nine years of age with the average probably around fourteen or fifteen. Today we would consider their treatment harsh but it had positive aspects. If the boys had remained on the streets of Britain’s urban centres their lives could have been worse. Many of them were orphans fending for themselves. In the cotton mills of Manchester they’d have been working twelve to fifteen hours a day for a pittance. At Point Puer they were housed, clothed and fed and had the opportunity to become literate and learn a trade. The colony was short of mechanics, and a trade as a stonemason, sawyer, nailer, shipwright, carpenter, etc. gave them a better chance in life than their contemporaries in England. The objective of making constructive colonial citizens out of transported teenagers was to be achieved by separation from adult convicts, with education, trade training and religious instruction being the vehicles to change immoral habits. A combination of management and resourcing issues, together with the defiant culture of many boys, resulted in the establishment producing mixed results. While some boys continued to offend as adults, others used their trades and pursued honest and successful lives.

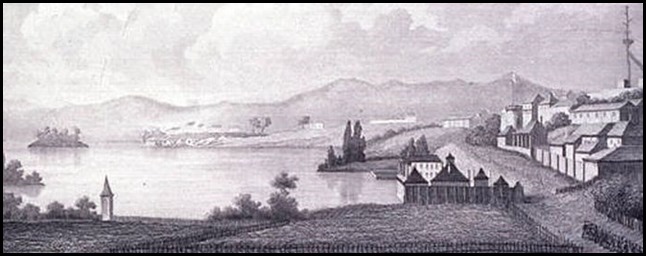

Point Puer peninsula and buildings can be seen in the background in this sketch by N Remand

On January the 10th 1834, sixty eight boys arrived from Hobart Town, on the Tamar, to take up residence. There is an amusing story, much told and recounted to us on our tour of Point Puer. It seems that Commandant Booth had arranged for a case of six dozens bottles of wine to be shipped to him on the vessel. Somehow the boys found the wine and consumed all but a bottle before they arrived, in a state of some intoxication, at the Port. Booth was not amused..... Booth appointed, with some apprehension, John Montgomery as the Superintendent of Point Puer. Montgomery was the ex adjutant of the 63rd Regiment and probably an alcoholic. To his credit Montgomery seems to have taken his duties seriously and within the year Booth reported most favourably on his conduct. In Booth’s first report on Point Puer he told of the routine which he had established for the boys. They were to begin and close their days with a prayer meeting. They would also have morning and evening lessons in literacy and numeracy and spend time during the day clearing land to grow vegetables. When the prison was more established he intended they also receive training as ”mechanics” (tradesmen). Having no precedent Point Puer evolved to meet its own needs and the requirements placed on it by the administration. The area of land they cultivated to provide vegetables varied with the number of boys, as did the number of tailors and bootmakers to make their clothing. When the noted Quaker missionaries Backhouse and Walker visited the Point in 1834 they were favourably impressed. Their report stated that the recently erected buildings included houses for the Superintendent and Catechist (a laymen who taught religion – mainly by rote), workshop, kitchen and barracks for the boys. The barracks (dormitory) was also used as a schoolroom and mess (dining room). At the time of their visit they reported that one hundred and sixty one boys were in residence.

All that is left of one of the ovens.

Booth had modified the boys’ routine when he next reported on Point Puer. “Up at sunrise – stow hammocks – wash and clean for inspection – prayers – field labour until breakfast at 8 am – 9 am muster to respective trades – dinner 1 pm – 2 pm muster for trades – 5 pm cease work – 6 pm supper – 6.30 pm school until 8 pm – prayers – sling hammocks, roll call, inspection then to bed”. The boys’ Sunday routine was as per the working week until 9 am. They did no further work but attended church services and Sunday School. They were issued with their clean shirt for the week and their soap allowance. Whilst this may seem a rather arduous routine the boys work was far less demanding and their diet far better than their free contemporaries working in the English factories of the day. he boys’ diet at this time was reported as being: Breakfast and supper; 10 ounces of bread and a pint of gruel made from sixty grams of flour. Dinner was the boys’ main meal and consisted of: 12 ounces of fresh or salt beef or 8 ounces of pork. 10 ounces of pudding made of 7 ounces of flour with the fat from the water used to boil the meat, or 1 pint of soap thickened with 1 ounce of flour. i pound of turnips or cabbage, or 1 pint of soup made from the meat and 8 ounces of bread or 8 ounces of potatoes in lieu of other vegetables. Each boy was also issued with one tin plate, one tin pannican (cup), and a knife, folk and spoon which were stored in a box in their mess. By 1835 Point Puer had its own tailor shop, in which the boys were taught the trade by convict overseers, and made the mainly sheepskin clothing the boys wore. Their annual issue of clothing was; 2 jackets, 2 pairs of trousers, two pairs of boots, 2 striped cotton shirts, 1 cloth waistcoat, 1 cap. On our tour we were told bullying was rife with the bigger boys taking the hammock strings from smaller boys. Gambled with buttons stolen from other boys shirts.

Our guide with the Isle of the Dead seen in the bay. It was here that the boys bathed in the shallow water. One lad from ‘the other side’ who had been working in the sawpit, wearing not just leg irons but dragging a chunk of wood, was made to bathe at the end of his working day. The guards who were keeping watch on the boys apparently warned the heavily weighted lad not to go too far out. He did, whether on purpose – no one knows - but he drowned.

All that is left of the saw pit. After Point Puer closed down, most of the buildings were demolished when the land was taken over by a farmer who wanted to graze his cattle.

The only remaining wall.

The water tank.

John Mitchell, a surveyor, arrived from England on the Marinus in 1837. He was appointed Superintendent of the establishment for convict boys at Point Puer. Once settled in that position, he sent for his fiancée, Catherine Augusta Keast, to join him. They were married at Hobart's Old Trinity Church in 1839. In 1848 Mitchell resigned from Point Puer and by 1854 had acquired Lisdillon Farm where he resided with his family. Under Mitchell's management Lisdillon prospered. He brought eight or nine families out from England to work as tenant farmers on the estate. A store, church, school room and post office were built to cater for the farmers and their families. Mitchell was soon able to acquire the neighbouring 'Mayfield' property and other real estate in the district. John died in 1880.

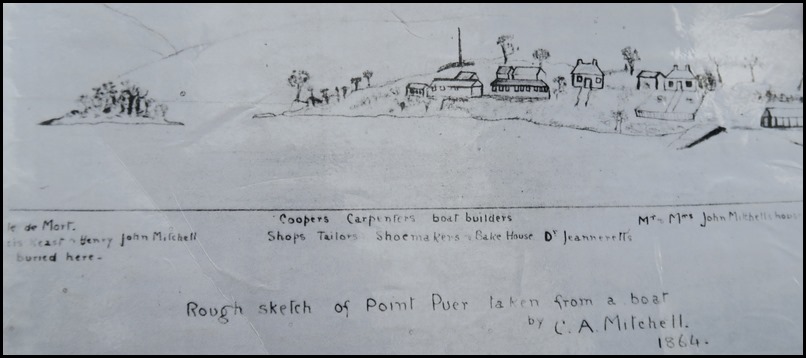

Catherine’s sketch of Point Puer, 1864.

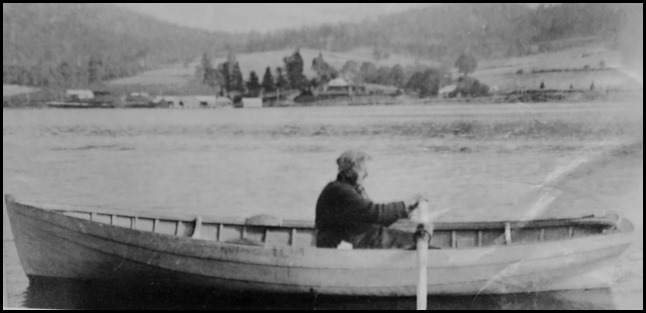

Our guide told us three stories of boys. One ended in an early death, one ended as a young man leaving Point Puer as a boot and shoe maker, setting up in business, marrying and his sons carrying on his business. Then there was Walter. Walter Paisley was thirteen years old when he was tried in Buckinghamshire, for breaking into a house. His brother, and four supposed friends, had lowered the little boy through a window – a year and a half later Paisley’s height was recorded as 1.25 metres. When the burglary went wrong, his accomplices ran off, abandoning Paisley. He was sentenced to seven years’ transportation. Shipped on the Isabella in 1833, Paisley was one of sixty-eight boys sent to the new juvenile establishment at Point Puer. The experience would not be pleasant. Over the next five years, forty four charges were entered against his name in the black books held in the Superintendent of Convicts’ office in Hobart. Many of these charges resulted in sentences to solitary confinement, a punishment with which Paisley was to become all too familiar. On average he spent two and a half days of every month at Point Puer locked up in the dark on a diet of bread and water. Some convicts hated solitary more than a flogging, itself a humiliating and degrading punishment. The prisoner John Mortlock succinctly summed up its effects, “of course, the brain is the seat of all pain, very dreadful”. Paisley’s first experience of solitary came just twenty seven days after the settlement opened. He was ordered to the cells for a week for insubordinate conduct towards Superintendent Montgomery. Five months later some of his friends were sentenced to solitary and Paisley amused them by sitting outside their cells and reciting obscene stories. For this he was locked up for a week. On another occasion he was punished for attempting to smuggle tobacco to a friend confined in the cells. When Paisley himself was locked up he refused to be quiet, singing, blaspheming and shouting obscenities. As time went on Paisley’s conduct became increasingly violent. He destroyed his work in the carpenter’s shop, struck a fellow boy with a spade, punched the schoolmaster and threatened others with a stolen lancet. After he was caught with a chicken which he had stolen from the Superintendent’s garden, he attacked one of the boys who had provided evidence against him He was released from Point Puer shortly before his sentence of transportation expired and he arrived in Launceston on Christmas Day 1838. Thereafter he managed to stay clear of trouble until the following year when he was arrested with a man named Thomas Dickenson and put on trial for burglary. For robbing the house of Felix Murphy in Liverpool Street he was sentenced to transportation for life. His sentence included the recommendation that he should be sent to Port Arthur for four years where, as a ‘bad character’, he was to be strictly watched. Back at Port Arthur he was up before the Commandant on another six occasions mostly for misconduct and disobedience of orders. He was discharged to the Colonial Hospital in Hobart in April 1844 and thereafter sent to the invalid station at Impression Bay. Judging from his official record, Walter Paisley’s life was a failure. He appears to have been an archetypal Dickensian street thief who at first refused to bow to authority, but in the end was broken and ground into the dust of the penal landscape - one more broken, pathetic life. This version of Paisley’s life, however, is taken from the State record. Paisley did not care much for books; while at Point Puer he was punished for ripping apart his catechism. Let us follow his example and place the written account to one side. In November 1998 there was a display of vintage boats at the Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart. The oldest boat there, the one which took pride of place in the display, was built in 1871 by fifty-two year old Walter Paisley. Surely Paisley’s real story lies in his handcrafted dinghy and the carpentry skills he chose to acquire at Point Puer in between the shouts and obscenities, the threats, the violent strokes on his buttocks and back and the two hundred days he spent locked up in the dark (Maxwell-Stewart and Hood, 2001, p, 10).

Mrs Dinah Wilson pictured in the Mercury newspaper in 1937 on her 88th birthday rowing her dinghy, built in 1871 by Walter Paisley.....

In 1846 under the administration of Charles J Latrobe, transportation ceased for two years. Point Puer was then twelve years old and its buildings suffering the ravages of time and situation. When Booth had selected the Point as the site he probably made the correct decision. He was occupied with establishing and building the port settlement, a difficult task, as well as overseeing the remainder of the Peninsula. It would have caused him a further unwanted task to have the suggested Slopen Main boys’ settlement in his portfolio. He was also unlikely to have foreseen the expansion of Point Puer. Point Puer was certainly not suited to the numbers it eventually housed. It was exposed to the severe weather which came in from the Southern Ocean. The timber resource was not great and, as fuel, was soon consumed, the very poor soil, combined with the lack of fresh water, made subsistent vegetable growing almost impossible. The digging of an aqueduct from Mount Arthur to the Point proved unsuccessful due to the lack of water available and the porous soil in which it was dug. Often fresh water and supplies had to be rowed across the bay to the boys. The success of the “Point Puer Experiment” is questionable. A cold, grey place.

ALL IN ALL OUR GUIDE BROUGHT IT TO LIFE QUITE BARREN BUT AN INTERESTING STORY |