Maritime Gallery Pt 1

|

Fiji Museum,

Suva

Maj, as Team Leader, does that very

thing, as we approach the Fiji Museum from the

botanical gardens.

The foyer housed a model of a typical Fijian village. We paid our two pound

thirty admission charge to a big, smiley lady and picked up an information

pamphlet which said:-

Located in the heart of

Suva’s botanical gardens, the Fiji Museum houses the most comprehensive

collection of Fijian artefacts in existence, including archaeological material

dating back 3,700 years and cultural objects representing both Fiji’s indigenous

inhabitants and other communities that have settled in the island group over the

last 100 years.

The concept to open a museum that

would display and preserve traditional Fijian culture was realised in 1904 when

Sir William Allardyce presented his collection to the Suva Town Board, resulting

in it being displayed in the Town Hall. The current museum building was opened

by the Governor of Fiji, Sir Ronald Garvey, in 1955. With the construction of

two adjoining sections in the 1970’s, today the museum boasts six gallery

spaces: the Maritime, History, Masi, Indo-Fijian, Natural History and Art, as

well as a temporary exhibition space and a gift shop.

The archives, photograph and

editing studio, reference library and administration offices are located

adjacent to the museum building in what was once the Nawela Hostel for Women.

Well, here William is mentioned, our

old friend Kenneth’s brother – he whose grave we saw on our bimble to see the

view on Mbulva.

We found

ourselves in the big open space of the Maritime

Gallery.

The first chap clearly didn’t have

our size of hip in mind and perched on the top would make us feel so exposed to

the big seas around these shore, deep admiration for these excellent sea-farers.

Built by professional Fijian carpenters [or, at the beginning of the last

century, by Tongan descendants, in the employ of a Fijian chief], the huge hull

being made from a single tree trunk. This deep-sea sailing

canoe will travel anywhere among the islands, transporting property for

the ceremonial exchanges [solevu], on deep sea fishing projects [especially for

turtles], and at one time on the business of war.

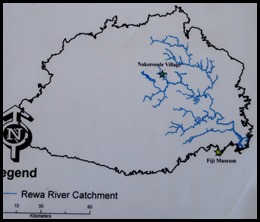

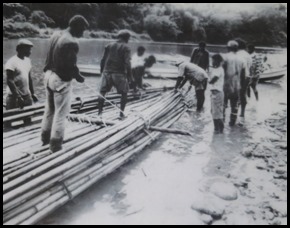

Bilibili –

House-Raft, H.M.S “No Come Back”. The Norokosule-USP bilbili was built

three kilometres upstream of Nakorosule village, Naitasiri, on the Wainimala

river. Rafts of this type are used for transporting farm produce from the most

inland part of Vitu Levu where there is no road access to the coastal markets

where they can be sold. Today river transport of

this kind is still very much the major transportation link for the river

villages up the interior.

The gathering

process.

The building

process.

Double Hulled Canoe – Ratu Finau

– the last Waqa Drua. The last waqa drua, also known as drua or waqa tabu, built by

craftsmen who knew the gigantic ocean going canoes of the eighteenth century.

The “Ratu Finau” was made in Vulaga [Fulaga] in 1913. Acquired by the Fiji

Museum in 1981, the canoe has been restored by the Museum’s conservation

section, assisted by Kepueli Cirimaitoga of Vulaga. Kepueli is the grandson of

the original builder, Amenio Moimatagi. Conservation work was supported by the

Fiji Sixes, the Australian South Pacific Cultures Fund and the general public.

The canoe was given as a birthday present to the Hon J.B. Turner in the early

1920’s.

Engineers [Fiji Military Forces] bringing the Drua on a

Williams and Gosling truck, 1981. Carrying the Drua

into the Museum. Reaching its final destination – the

Fiji Museum.

Dimensions: As a comparison of

her steering oar with a massive steering oar displayed alongside the canoe, the

‘Ratu Finau’ is relatively small for an ocean going Fijian canoe. Kata – main

hull = 13.43 metres. Cama – outrigger-second hull, which is somewhat smaller

than the main hull = 12.18 metres. Domodomo – mast = 7.92 metres. Deck platform

= 5.50 x 3.31.

The lengths of the Kata hulls of

some of the plank-built canoes [drua] of the 1800’s were: “Rusaivanua” – 35.97

metres. “Dronivere” – 32 metres. “Lobakitoga” – 30.25 metres. “Ramarama” – 30.18

metres. “Batinika” – 26.27 metres and “Jone” – 25.60 metres. We cannot

imagine what it would be like to go to sea in one of these ladies, let alone

control, navigate and vital. Scary and vey

exposed.

Model of the

Canoe – one tenth of the actual and a drawing of one

in action. Drua is by far the largest and certainly one of the most

remarkable traditional Fijian artifacts ever to join the collection of the Fiji

Museum. The traditional Fijian double-hulled canoe has been long regarded as the

most seaworthy of the large voyaging canoes built in Oceania. We’ll take

their word for it.......

Domodomo – masthead. This massive horned masthead comes from the last ocean going canoe, the Ramarama. A final link in a chain of great druas of the name built for the Tui Cakau by his Mataitoga, the descendants of a clan of Samoan canoe builders [Lemaki] who were brought to Fiji from Tonga in the late eighteenth century. She was built between 1872 and 1877, drua of her size and quality generally being under construction for 5-7 years and on completion was presented the Tui Cakau to Cakobau, Vunivalu of Bau. After Cakobau’s death in 1883 she was returned to Somosomo where she finally decayed and was broken up in 1892. Her masthead was 4.32 metres long. Now we understand why all Fijian public telephones have what we thought was a fancy spear all called Drua.........

The display case next to the domodomo had my immediate and complete attention. Perhaps not everyone’s cup of tea........and certainly a bit more to it than just heaving a body into a cooking pot, making a stew as a voice in the background says “Dr Livingstone I presume”. Not to mention all the words that are pronounced nothing like how they look....... Cannibalism was an integral part of Fijian religion and warfare. Enemies slain or captured in war were those most commonly eaten, little respect paid to age or sex. Bodies were dragged to the temple to the tolling of the death drum amid scenes of wild excitements, including the cibi death dance of the men and the obscene dele or wate dance of the women, in which the bodies were sexually abused, The priests offered the bodies to the war-gods, the heads often being smashed against a stone pillar outside the temple, sacrificing the brain to the gods. The bodies were then cut up, cooked in earth ovens, and eaten – priests and chiefs receiving the better portions. Women seldom ate human flesh – well draw me with a relieved look on my face. Captives were severely tortured before being killed. The whole body was generally consumed, [but in times of plenty, following massacres] the trunk, head and hands were thrown away. Skulls of famous enemies were made into yaqona cups, while shin bones were made into sail needles.

Cannibalism was always a highly ritualized event, and bodies were eaten as part of a religious ceremony, often accompanied by special chants and rituals. Consumption of a body was the critical act in the process of human sacrifice. Generally, those eaten were enemies killed in war, but other categories of people [conquered people, slaves] could also be legitimately killed to acquire bokola at any time. This was necessary because certain regular events required human sacrifice: the construction of temples, chief’s houses, and sacred canoes, or the installation rites of a chief. The paramount chief had special assassins [sometimes Europeans] who would procure these victims, usually by ambush. The eating of such victims by the priests and /or chiefs meant that the victim was being totally destroyed or annihilated both physically and spiritually, hence the eagerness of warriors to bring back bokolas in order to wipe out their enemies. Also in order to avoid the enemy “wiping them out”, they were keen to bring back the bodies of clansmen who had fallen during battle. The eating of human flesh was a way of showing power...absolute power over one’s enemy. Most bodies eaten were those of enemies taken in war, but if bodies were required for religious and feasting purposes and no war was in progress, then slaves or low caste people became bokolas. In addition to these, passengers of shipwrecked canoes were almost always invariably killed and eaten. The bodies were generally cut up and prepared for the oven by a priest using a bamboo knife, simply splitting a new edge whenever it got blunt. And if there was a large supply, ordinary men and even women helped in dissecting and preparing the bodies for the oven. The human skull above. Bilo Ni Yaqona or kava cup called Radinadina. It was made at Drawa, Dreketi. The bilo was named after the kalouvu [spirit god] Radinadina who was a notorious cannibal. Rokoligana, a boy chief of Dreketi, saw several prisoners from Cikobia in the bi-ni-bokola or cannibal stockyard at Drawa and was given a boy prisoner to club to death in practice. Having killed, he asked for the shattered portion of the skull. The forehead made into a bilo [cup] for him to commemorate his first kill. Rokorakadrudru [priest] made it for him at Drawa, anointing it with blood and brain and smoking it in the Burekalou [Priest House] before taking it to the young chief at Naua, Dreketi.

Limb bones of cannibalised men and women, jammed as trophies into the fork of a huge molikana or shaddock tree; Namosi, southern highlands of Viti Levu. Bones represented include the humerus, femur and tibia of at least three men - one of whom was a hobbling cripple – and a woman. There is no doubt about their being cannibal relics, various butchering scars on the bones bearing out both historic references and oral traditions to this effect. In western Viti Levu, where there were no canoe powers, and in the highlands of Viti Levu generally, where there is no call to reserve limb bones for sail needles, cannibalised bones were often hung up in shaddock trees outside spirithouses and men’s houses, forming durable trophies as the growing wood slowly engulfed them. Witchcraft sticks – Titoko Luveniwai – with human bone top. Previously used in witchcraft by the Dreketi chiefs. Presentedby Ratu Isirefi Raqica, Roko BuliDreketi, Drawa, Dreketi in 1983. An extravagant hairstyle depicting male pride, to shave the head was a profound religious or mourning sacrifice. The prematurely bald, old ‘dogs’, and men who were re-growing their hair following a period of mourning; hiding their shiny or bristly pates beneath beautifully crafted human hair wigs, often dyed in grey, buff, red and black ruffs and whorls, and generally fastened, as in this case, to a coir sinnet net, fitted with a marginal drawstring. When not being worn, the wig was stored inside-out. The story goes: Human bone necklace or I Taube Sakisaki Ni Bokola. According to Ratu Katonivere, Tui Sasa, Tui Vuniwesi and Ratu Ligani, Tui Dreketi of Macuata, Vanua Levu [cousins] were responsible for making these. They met privately in Yabeyaga and agreed to take the Bokola bones from under the house posts during the night. They dug out the remains of Rororobu – a warrior, Masiuolo – a hunter from Nabunidau and Robovucu of Tidoyaga. These men had, long before been buried to hold the two sacrificial posts of Yabeyaga. The bones that were not used were returned to the hole. I Taube Sakisaki was made by the Dualagilagi leader of the Dreketi mataisau.

The celebrated shaddock grove and rara at Namosi, showing the rows of stones commemorating cannibal victims. Assuming that similar practice was followed here as elsewhere in Viti Levu, the taller stones probably recall the killing and eating of chiefs. Sketch by Arthur J.L. Gordon, 1877.

Cannibal fork

or as we call it a brain picker......more correctly – I Cula ni Bokola. A

chief’s or priest’s fork, used when eating human flesh. The meat of a defeated

enemy was sanctified hence their use was restricted to certain chiefs and

priests who, as living representatives of gods, could not properly handle any

food whatsoever only either being fed by an attendant [whose hands were

consequently tabu [sacred] who would place the food carefully in the chief’s

mouth, scrupulously avoiding contact with the lips. This fork having been in

contact with unsanctified fingers was tabu and could not be handled by ordinary

mortals eventually becoming a religious relic in its own right. Twenty five

and thirty thousand pounds has been handed over at auction for famous brain

pickers. We have seen them at one pound fifty in the handicraft market for one a

bit bigger than a dinner fork, right up to four foot long, very heavy and a

couple of hundred pounds. A couple of years ago a ceremonial set sold for thirty

thousand pounds............. Some are very elaborate, some have rattles in the

handle but not for Beez Neez.

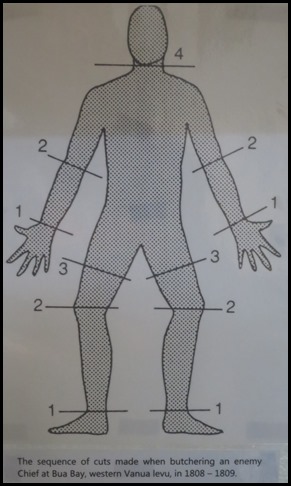

Sequence of

Cuts - There was an instruction manual for

this.........????

Massacre at Bua, Vanua Levu in

September 1813. Captain Dillon and two other survivors. The grave of Udre

Udre located along the Kings Highway, in Rakiraki – Oh this is a

must visit then.......he holds the Guiness Book of Records for the most prolific

cannibal.

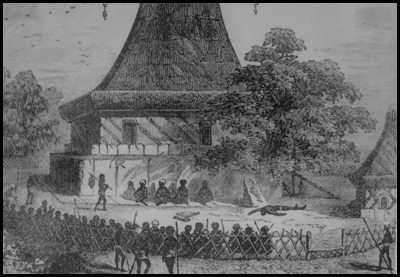

The Missionary

Station at Bua Bay from a drawing by Lieutenant Shipley in

1848

Sandalwood Trade 1800-1820. The

handful of foreign vessels which had strayed into Fiji waters during the 1700’s

escaped shipwreck. But, with the new century, the inevitable happened. In

January 1800 the American Schooner Argo, bound from China for Port

Jackson, Australia, was wrecked on the Bukatatanoa Reefs and her surviving crew

members spread about Fiji. The Argo bore disease as well as cargo, and a

devastating epidemic, the “lilabalavu” swept the islands, killing thousands of

people. This was just the first of a series of epidemics which greatly reduced

the Fijian population during the nineteenth century. Disease coupled with

demoralisation in the face of unprecedented change saw the population fall from

perhaps 250,000 in 1800 to a low of 85,000 by 1921.

Disease was not the only consequence

of the Argo wreck. In 1804, one of her crew, Oliver Slater, brought

word to Port Jackson that sandalwood grew abundantly about Bua Bay on Vanua

Levu. This scented timber fetched fantastic prices in the Orient. As a result,

Colonial vessels from Port Jackson, along with East Indian traders from

Calcutta, and Yankee merchant seamen from New England, began converging up Fiji

which for the first time offered a commercial attraction.

By 1814, all of the sandalwoood had

been cut out of the area and ships again shunned Fiji until the onset of the

beche-de-mer trade in the 1820’s.

After all that I needed a rub down with slugs on

toast........yuk........

Beche-de-Mer Trade

1800-1860. Smoked-cured beche-de-mer sea slugs, a Chinese delicacy,

fetched high prices in Manila, and from the late 1820’s to 1860’s formed the

main item sought by foreign traders in Fiji. Ships from Salem, Massachusetts and

New England dominated the trade. Their Yankee captains played a key role in

Fijian political history by keeping chiefs of Bau, in particular, well supported

with arms, ammunition and the diplomatically essential whales

teeth.

Captain William

Driver who, as mate of the Clay, employed mutineer Manila-men he found in

Fiji to smoke beche-de-mer by a method hitherto unknown to Americans. The

staggering profits earned when his cargoes were sold in Manila in the late

1820’s sparked the Fiji beche-de-mer trade. The Glide, which dragged her anchors in a

hurricane in 1831, was one of many beche-de-mer trading ships wrecked

here.

Captain John H

Eagleston of the Peru, Emerald, Mermaid and Leonidas of Salem was the

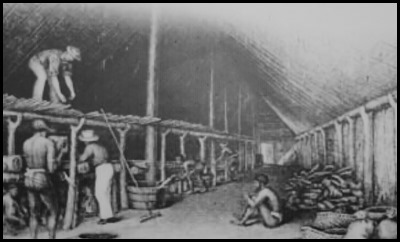

most flamboyant of the beche-de-mer traders in the 1830’s. Captain Eagleston’s beche-de-mer curing shed or

‘batterhouse’ in 1840. Each captain contracted a powerful chief who sent a

thousand or more divers to gather sea slugs and hundreds of men cut firewood

with which to smoke them. The slugs were gutted and boiled,then dried over a

smouldering fire in a long shed. Fishing and curing took months with several

shore stations supplying each ship.

Captain Benjamin

Wallis of the barque Zotoff, a

predominant Yankee trader of the 1840’s. His wife Mary, who accompanied him,

left an intriguing insight of the Fiji beche-de-mer trade in her book “Life in

Fejee”.

ALL IN ALL A ‘NOT TO BE MISSED’

GEM

AMAZING INSIGHT INTO FIJIAN

LIFE |