Chinese Miners

|

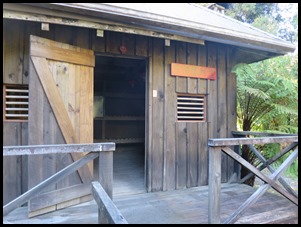

The Chinese Miners    Our Shantytown visit gave us a unique

opportunity to look at the world of the Chinese miners, we began in a large hut and read all the information boards with

interest. Bowls and knick-knacks along one wall,

opposite a fireplace all

authentic.

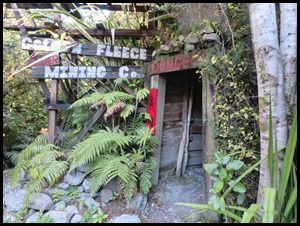

Next we were in a

recreated general store. Bigger than this usually, but this size might be

found at remote mining localities. Chinese stores sold a wide range of both

European and Chinese goods and tried to supply everything that their fellow

countrymen might need on the goldfields. Europeans also visited these shops,

often to purchase fruit and vegetables grown locally by the

Chinese.

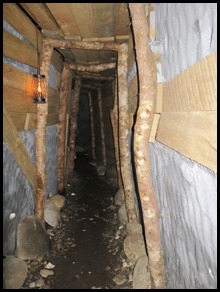

There was a

replica mine to get a feel of the cramped, cold and dark working

conditions.

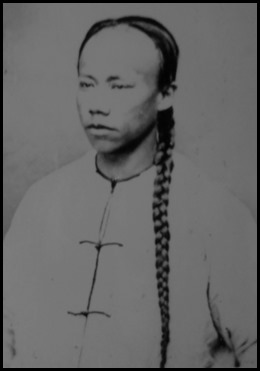

Unknown Chinese

man 1870’s.

The arrival of the Chinese wasn’t met

with enthusiasm by the predominantly European mining community. “They are

different to us.” Not only did the Chinese look different with darker skin,

baggy clothes and long pigtails, but they also had different religious beliefs,

AND worked on Sundays. Because they didn’t intend to stay in New Zealand many

Europeans thought the Chinese were not useful immigrants.

Where did they come from ? Almost all

of the Chinese who came to New Zealand goldfields came from the Pearl River

Delta, in south-east China’s Guangdong – Canton, province.

Why did they leave China ? During the

1800’s the people of the Pearl River delta were suffering considerable

hardships. The area was over-populated and many people lived in poverty. In

addition they were suffering from the destructive effects of British Imperialism

and the opium trade. For many of the rural poor the solution was to send sons

and bothers to work overseas. The money they sent home could be the difference

between life and death for their families. It was also thought they would return

to their village as rich men, enhancing their family’s position. Mainly they

went to the goldfields in California and Australia but some came to New

Zealand.

Why did they come to the West Coast ?

The gold-rush on the West Coast in 1865 offered new opportunities and by mid

1866 Chinese were arriving here, coming either from Otago or from the gold

fields in Australia. Not all of the Chinese came to work as miners, they were

also storekeepers, cooks, gardeners, at least one Chinese doctor and sadly opium

dealers. The population of Chinese miners fluctuated, with successive miners

returning to China as soon as they had saved at least a hundred pounds – six

thousand pounds-ish in todays money. For a lucky and frugal miner this would

take about five years.

Grey River Argus, 5th of February

1867:- “We learn that the first installment

of Chinese, fourteen in number, arrived in Hokitika on Friday from Sydney and

their presence caused quite an excitement, the wharf being lined by a large

crowd of persons, who shouted and yelled vociferously, and so frightened the

unfortunate Celestials that they dived under the hatches and postponed their

landing until an opportunity presented itself.”

In some of the smaller mining

settlements, such as Stafford, No Town and Maori Gully, Chinese miners were

jostled, abused and in one case stoned when they first arrived.

Grey River Argus, February 1872:-

“.....although no great amount of violence

was used toward them beyond pulling and pushing them along the road, some forty

to fifty people joined in the crowd and the Chinese were sufficiently alarmed to

run for their lives.”

After initial reports of intimidation

it appears that things usually settled down. Warden Fitzgerald wrote in April

1874 that “the good feeling to which I referred in my last report as

existing between the Europeans and the Chines still

continues.”

Letter from Long Wah to the West Coat

Times on the 8th of May 1876:- “I claim for

my countrymen the credit of being, here as elsewhere, a harmless, inoffensive,

hardworking, and persevering section of the community, conforming with your laws

and contributing to the revenue of the Colony.”

The overall reaction of West Coast

Europeans was, however, probably one of suspicion and dislike, especially when

the country experienced periods of economic decline starting in the mid 1970’s.

Anti Chinese feeling was partly fuelled by the idea of losing jobs to the

Chinese.

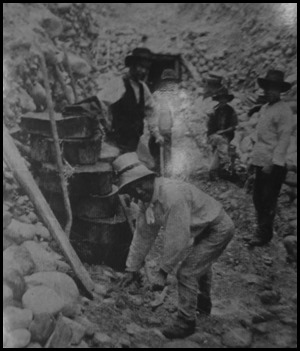

Bamboo water wheel. Miners working

Greenstone, near Kumara. Miners sluicing Blackwater, near

Reefton.

The Chinese have a long history of

engineering works based on simple labour intensive technology. In New Zealand

the Chinese miner was not averse to working over ground which had already been

tried by European miners and used traditional methods, such as wing damming,

water wheels and pumps to good effect. They were

systematic workers who were prepared to work long hours.

Caleb Whitefoord, Warden, No Town,

April 1874:- “I believe the introduction of

the Chinese here has been productive of much benefit, as they have reopened

old-tail races long since abandoned and blocked up – and which the ordinary

miners would not have gone to the expense of repairing, and by doing so have

drained and rendered available for mining purposes a large tract of ground

besides that which is taken up by themselves. They have also erected large wing

dams in the creek, and by means of these, and water-wheels, are working very wet

ground that the other miners would not take up.”

Otago Witness, 9th of October 1875:-

“John Chinaman is not only a patient worker,

but he is likewise a skillful engineer, and many a useful hint have the

so-called enlightened Europeans been glad to borrow..... Their system of dead

level tail ditches fitted with those ingeniously-contrived dummy sluice

entrances which, while admitting all water, keep back the gravel and silt,

together with their admirable manner of constructing dams and river

walls......prove the ‘heathen Chinee’ to be anything but........stock of

knowledge we should make light of......”.

The goldfield’s wardens were

unanimous in praise of the Chinese and their comments on the Chinese in their

districts are littered with words like ‘industrious, peaceable and

well-conducted’.

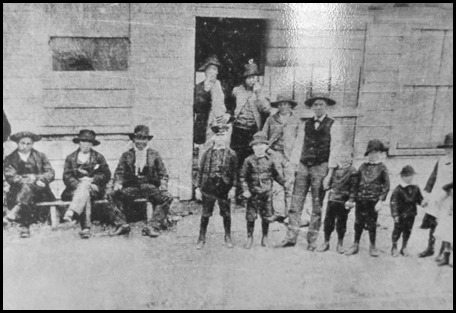

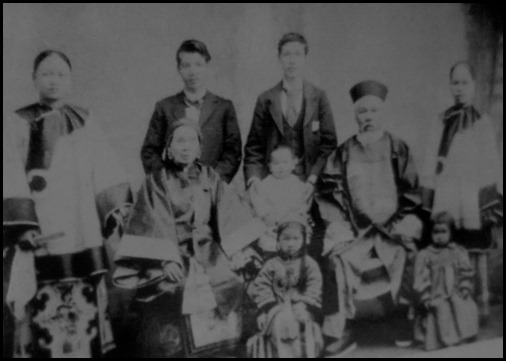

A group of Chinese

men and children at Kumara, 1897.

The Chinese looked for ground which

would provide a steady income and where they would be allowed to work in peace.

Huts were generally simple with a chimney near the door, few windows and were

sparsely furnished. There would be a sleeping platform, boxes for food storage,

a meat safe and wash buckets. Inscriptions on red paper were common both inside

the huts and on the outside to greet visitors.

Reminiscences of Jack Aynsley:-

“They were hardy. There was no lining in the

huts except sometimes a piece of rice-bag along the wall by their bed and only

rice matting for a mattress. They would have either a block of wood with an old

piece of cloth on it for a pillow or a round log to lay their necks

on.”

Reminiscences of George McNee,

1880-1946:- “I never saw a dirty or untidy

Chinese whare – they were crude, with no lining on the walls, earth floors and

so on, but their tables, cooking utensils etc were spotless....I was pleased to

arrive at the Chinese place.... and have a clean cup of green tea and some fried

chop suey placed before me with the utmost cleanliness and hospitality”.

When in New

Zealand the Chinese adhered to their traditional beliefs one of which obliged

people with a common ancestor or relative to help each other. In New Zealand the

family was extended to include people from the same country. In the early days

the Chinese often worked in groups – almost always with men from the same clan

or village as themselves, and lived in camps either of individual huts or one

big community dwelling.

Chow Sing,

market gardener of Akaroa, around 1898.

West Coast Times, 4th of August

1868:- “On the south side of the Hokitika

River gardening operations are being pushed forward with great vigour, not alone

by Europeans, but also by those most industrious and successful horticulturists

the Chinese....four acres of land have been leased by five Celestials under the

leadership of Mr James Ah Che...... They have already cleared the greatest part

of the section, and placed nearly an acre of crop.”

Reminiscences of George McNee

1880-1946:- “Ah Ten, who was a market

gardener, was one of the better-known members of the Chinese community. He was

seen regularly walking from Welshmans to Paroa and then to Greymouth carrying

baskets of vegetables across his shoulders. On the return journey the baskets

would be filled with rice. They were thin, active men of short build, weighing

as they said “allee same bag of rice” – that was around eight stone...... As

they were such small men it was surprising the weight they could carry in their

baskets, one on each end of their poles.... That was how they transferred any

weight or quantity of goods from one place to

another.”

Chinese

gardener, around 1882 by H.J. Graham. Chinese miner next to his garden at

Waikata, Southland around 1900. With him is Presbyterian Missionary Rev. A. Don.

– Alexander Turnbull Library.

There is no definitive record of what

the Chinese gold miners ate but it is likely that their staples were rice and

vegetables flavoured with whatever meat was available and traditional sauces and

spices. Most Chinese miners had a small garden to supply themselves with

vegetables and any surplus would be sold to other settlers.

Reminiscences of Jack Aynsley:-

“The Chinese could live on four or five

shillings a week, all they used to live on was rice. But when they were getting

good wages they used to live it up and would buy all the fowls they could get.

My mother must have sold them over a hundred”.

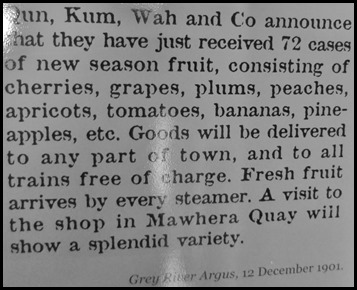

Until the turn of the century there

was quite a number of Chinese stores with the main towns being Greymouth,

Hokitika and Reefton. Chinese storekeepers would import large quantities of rice

tea, preserved vegetables and condiments as well as Chinese alcoholic beverages,

fireworks and herbal medicines. Greymouth was the largest business centre for

West Coast Chinese and in 1900 there were about twenty men who described

themselves as merchants, storekeepers or fruiterers. At this time there were

also several boarding houses and a billiard saloon. Chinese storekeepers were an

important part of the community, their shops acting as meeting places where news

could be exchanged. As the storekeepers could usually read and write both

Chinese and English they were often called upon to act as interpreters and

letter writers.

Altar in the Joss

House.

The Chinese miners adhered to a

complex mixture of beliefs and customs drawn from three major religious

doctrines in China – Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism. The Chinese had a strong

belief in evil spirits and the supernatural and had many rituals designed to

keep away evil or invite good fortune. Ancestor worship was very important to

them and they worshipped many different gods. The five Chinese virtues are

humanity, integrity, courtesy, wisdom and truth.

Some of the Christian churches sought to convert the “heathen”. Although the Chinese were very polite and often prepared to listen to sermons, very few converted to Christianity. The Chinese had great faith in their traditional religions and they were also worried about what the spirits might do if they stopped worshipping the souls of their departed relatives.

The Eight Immortals are from Taoist mythology. They represent the eight conditions of life. From left to right: He Xian-gu – feminine. Zhong Li-quan – wealth. Han Xian-zi – the common people. Cao Guo-Jiu – nobility. Zhang Guo-lao – old age. Lan Cai-he – youth. Lu Dong-bin – masculine and Li Tie-guai – poverty. Throughout China they are known as the symbols for good fortune.

Breeding of goldfish for colour and shape began over a thousand years ago in China and the fish were highly valued especially by the Imperial families where yellow varieties were the most prized. As the word for fish sounds very like that for abundance so gold-fish symbolises an “abundance of wealth or gold”. An immortal child with a large goldfish and lotus blossom is a common theme for New Year motifs symbolising “successive years of abundance”. Cards for newlyweds often show a pair of goldfish wishing the couple future wealth and faithfulness. Goldfish are often kept in ponds or aquarium as a symbol of future wealth with eight gold or eight gold and one black fish being the luckiest numbers. The first goldfish were introduced to North Island in the 1860’s and their use in ponds rapidly spread. They can now be found in isolated streams and ponds and are not seen as a hazard to indigenous life. Symbolic of ongoing wealth, gold fish

would have been especially significant for the Chinese gold diggers on the West

Coast.

Local Chinese taking part in the Greymouth Queen Victoria Jubilee Parade in 1897.

When in New Zealand the Chinese continued to celebrate significant events. New Year was the most important annual festival. Several holiday days would be taken and there would be big feasts at each of the Chinese settlements. Thomas Feary, Grey River Argos. 20th of July 1960:- “My father, who was friendly with the Chinese, often used to take me with him on his visits, and I will never forget one time when they were celebrating their New Year, and the large hut was decorated with Chinese lanterns and illuminated by numerous coloured candles. The table was laid out with good things of all descriptions such as I had never seen before and, as if a small boy of my age symbolised the children of their own country, they lavished sweets and gifts upon me.”

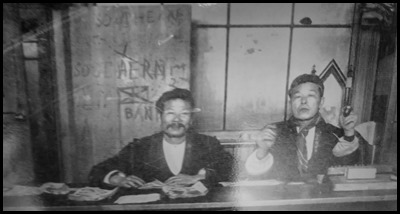

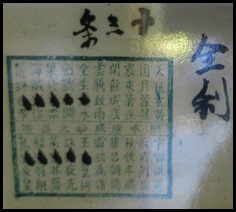

A pak-a-poo gambling

shop, Dunedin 1904. Pak-a-poo lottery

ticket.

The Chinese miner was generally extremely

industrious but when he had time off he seemed to have been determined to enjoy

it. They worked long hours at a tedious job and gambling, as well as being

socially acceptable, provided excitement and a chance to relax with friends.

Fantan, pakapoo and later dice were the most popular gambling

games.

In the Chinese miners home province of

Guangdong opium addiction had reached epidemic proportions. Many of the miners

brought their addiction with them while others took up opium smoking in New

Zealand as an escape from hardship and loneliness. It has been estimated that

about ten per cent of the Chinese miners were addicted to opium with as many as

sixty per cent smoking occasionally.

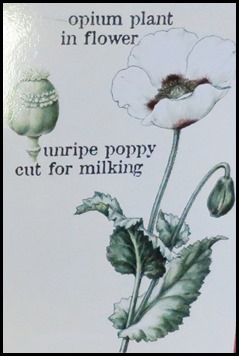

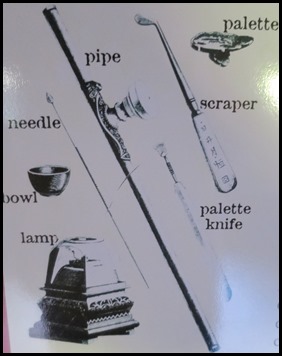

Opium

poppy and paraphernalia.

Opium is the milky fluid which leaks out

of the unripe capsule of the poppy when it is cut. This hardens to a resin with

exposure to the air. The narcotic effect of opium is obtained by inhaling smoke

given off from a piece of heated opium resin and is traditionally smoked in an

opium pipe.

Tobacco smoking was common among the

Chinese miners and Rev. Don commented that “a non-tobacco smoker is about as

rare as a non-tea drinker or non-rice eater.”

Alcohol consumption was an accepted part

of Chinese life and traditional drinks were fermented grains or starches. In New

Zealand the Chinese drank brandy, gin, whisky and beer but there were very few

reported cases of Chinese drunkeness.

Few Chinese women came to the goldfields;

in 1878 there were only nine Chinese women, and only eighty nine by 1900. Most

of the miners could not afford to pay for their wives to come out to New

Zealand, especially after the introduction of the one hundred pound poll tax in

1896.

The women who did come here were usually

the wives of wealthy merchants. In the late 1890’s there were at least six

Chinese women living in Greymouth, four of whom were married to Luey Goek, Tso

Fong, Young Saye and his father Young John, all merchants. Another was the wife

of a Chinese Presbyterian Missionary – Timothy Loie.

Occasionally a successful miner, market gardener or cook might marry a local woman but this was the exception rather than the rule. When Chat Sing – a storekeeper from Stafford, married seventeen Charlotte Grey the local paper, the Kumara Times of the 12th of October 1888 reported:- “The unusual event excited great curiosity, which was increased by the newly married couple driving in state down the Revell Street, Hokitika in the afternoon, attended by European friends, there being three buggies in all, and having their photograph taken at Mr. John Tait’s. The bridegroom is described as being celestially handsome. Prior to the party leaving a store in North Revell Street, where a goodly crowd of almond-eyed brethren had assembled, they were treated to a heavy fire of rice, a ceremony which John looked as if he could have dispensed with. They then proceeded to their future home in Stafford, where they gave a free ball and supper in the Oddfellow’s Hall to their European friends, and a supper to their Chinese admirers in one of their own stores.” For the Chinese women who came to New Zealand described as being “dressed in the most elegant of oriental costume and silks, with feet only inches long”, Greymouth must have been in some sort of conniption.

Annie Ah Long with her son

Harry, 1900.

Annie - Tang Ah Moy

was born in 1879 and came to New Zealand to marry Ah Long, a storekeeper at

Ahaura, when she was seventeen. The couple had seven children and ran a store

and market garden. At one time Annie had her own sweet shop and during the

1930’s she had a laundry in Greymouth, it was there that her husband died in

1930. Annie died in Oamaru in 1963.

Harry Kin Hong Long and his siblings went

to school in Ahaura. After leaving school Harry worked at various jobs while

studying engineering by correspondence. In late 1922 he passed the NZ Government

Engineering Exam. In 1932 he was offered the job of Engineer Superintendent at

the Hong Kong and Yaumati Ferry Company, a position he held for thirty five

years.

Young John, a

merchant in Greymouth, with his wife, his two sons, Young

Hee – on left and Young Saye along with their wives and his grandchildren in

1901.

Young Saye

arrived in Greymouth in about 1887 when he was seventeen years of age. His

father, Young John, ran the Kwong Lai Yun store and had been in Greymouth for

some time. His elder brother, Young Hee, who worked as a law clerk had arrived

about a year earlier. By 1893 Young Saye was a storekeeper in the town. The

Young family were important to the Chinese community, acting as agents, bankers

and interpreters as required.

Young Saye’s father and brother left

Greymouth in late 1901 but Young Saye stayed and continued with the storekeeping

business. His wife, Tsao Oi Ling, was married to him by proxy while still in

China and then travelled to New Zealand. She didn’t know a word of English and

had tiny bound feet. One can only imagine the enormous culture shock of crossing

an ocean and trying to hobble off the boat to find your husband.......

The boys in the picture went to local school and

one of the dons, James, won the school’s Watkins Medal – awarded annually to the

best scholar, in 1913. The family left Greymouth for Hong Kong in late

1915.

Many Chinese did make enough money to

return home rich men, but as the numbers of new arrivals dwindled the men who

remained were often those who had experienced bad luck or who were perhaps not

as frugal. There was also the occasional miner who did not want to return to

China.

By the 1920’s and 1930’s only a small

number of Chinese remained on the coast. There were still wealthy storekeepers

but as time passed those who relied on manual labour became increasingly

dependent on charitable aid.

T.F. Loie, West Coast Chinese Missionary,

September 1908:- “Those who are still

vigorous keep working diligently with the hope of making a living. As the years

and months are added to their age, some make enough for food, but insufficient

for clothing; if they are well clad then they are ill-fed. As for those frail in

body, who can imagine fully their pains and toils ?”

New Zealand introduced an Old Age Pension

in 1898 but Chinese were specifically excluded from receiving it. This was

repealed in 1936.

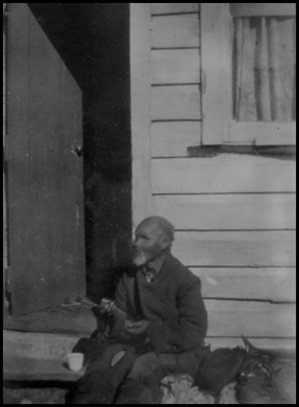

Presbyterian missionary Dr. John Kirk

describes a visit to Blue Spur, Hokitika in

1907:- “He has seen fifty New Zealand winters

come and go since he first came to the ‘gold hills’ to seek his fortune. His

grey hair is matted and long, and his brown face tanned with long exposure to

many weathers; but there is a bright light in his eyes when he hears one of the

strangers greet him in his mother-tongue. he is not slow to lay aside his spade,

and as one watches him there talking of past years and of his far-off friends

and home, one feels the pathos of it all. For, as we look on this old son of

toil, we know he will never see his beloved China again; but as he has lived so

he will die; in a strange land far from kith and kin.”

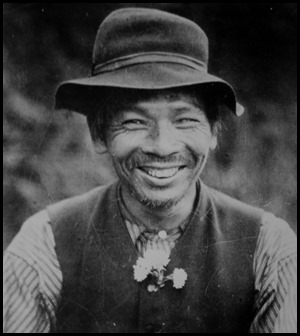

Kai of Rutherglen circa 1920’s and years later.

Recollections of Sam Hayden 1901-1988:- “One very small Chinese, named Little Kai, was quite a character, with an infectious grin. He frequently called at our place to purchase tobacco, and my mother kept a special cup to give him some tea. On one occasion, Mother told him the kettle was not boiling, so she gave him a cup of milk, whereupon, with his likeable grin, he said. ‘Whisky much better, Missus’.”Kai lived in a hut near the entrance to Shantytown. He had lost an eye in a mining accident and lived in semi-retirement. He died in Greymouth in about 1930.

Reminiscences of Jack Aynsley:- “We were going into Kumara one evening when one of the Chinese men had just ben killed at Westbrook through being swept through the race. They had him lying beside the road with two big fires to keep the devil away. They were bending over and waving their hands, some of them with tears running down their cheeks.” Europeans were fascinated by Chinese funerals and sometimes a description of one would appear in the paper. West Coast Times, 31st of August 1889:- “The cemetery was crowded yesterday afternoon, the occasion being the funeral of Sam Sing who will be remembered as cook for a long time at the Empire Hotel..... The deceased was arrayed in full dress and wore his hat as one was prepared for a long journey. In his mouth was a half-a-crown, the toll expected by some exacting deity. Shillings were distributed to those Europeans present, a part of the ceremony which seemed highly appreciated and might with advantage be imported into our funerals during these dull times. For the rest there was great firing of crackers....there was also lollies and the serving out of much fire water. In order that the deceased might not hunger on his long journey home, a plentiful supply of provisions was heaped on the grave....a bowl of rice, hard boiled eggs split in halves, and, better than all, a savoury roast duck. The mourners during the ceremony wore white crepe on their hats which directly the funeral was over they burnt on the grave.”

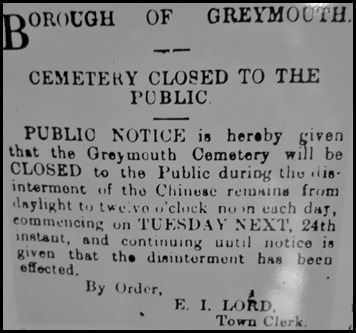

Cemetery Notice

- Grey River Argus, 1st of October 1901.

The Chinese tradition of ancestor worship

meant that it was important to return to China so that their descendants could

worship their burial site. If it was not possible to return home during their

lifetime they might be sent back to China after their death as Sin Yan – former

men. Chinese were exhumed from West Coast and other cemeteries in New Zealand

during 1900 and 1901. It is estimated that at least one hundred bodies from the

West Coast were part of the shipment of four hundred and ninety nine bodies

being sent home on Ventnor. Unfortunately the Ventnor sank with no survivors off

the coast of New Zealand in October 1902. What a terrible shame.

ALL IN ALL A WONDERFUL INSIGHT

INTO THESE HARD WORKING LITTLE PEOPLE

INDUSTRIOUS, WELL TRAVELLED AND FAR FROM

HOME |